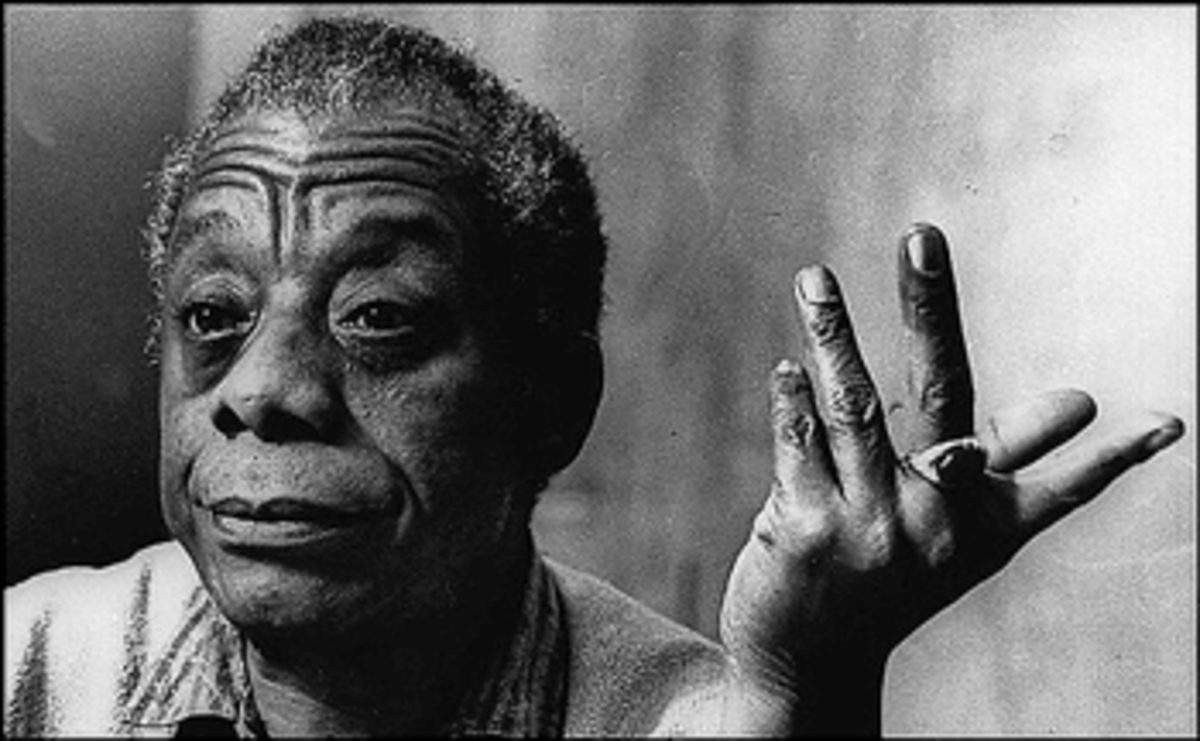

The writer James Baldwin once made a scathing comment about his fellow Americans: “It is astonishing that in a country so devoted to the individual, so many people should be afraid to speak.”

As an openly gay, African-American writer living through the battle for civil rights, Baldwin had reason to be afraid — and yet, he wasn’t. A television interviewer once asked Baldwin to describe the challenges he faced starting his career as “a black, impoverished homosexual,” to which Baldwin laughed and replied: “I thought I’d hit the jackpot.”

Several of Baldwin’s essays, speeches and articles are collected in a new book called The Cross of Redemption. Randall Kenan, who edited the collection, talks to NPR’s Steve Inskeep about Baldwin’s complicated identity — and how his work challenged black and white readers alike.

Baldwin wasn’t afraid to speak out, but that didn’t stop critics from trying to silence him. Kenan says Baldwin was “mysteriously” removed from the list of speakers for the March on Washington in August 1963.

His sexuality often came up when he dealt with conservative religious organizations, Kenan says. And when he tried to help the Black Panther Party in the 1970s, his sexual orientation was “thrown up at him in very hurtful ways.”

Baldwin was quite open about his sexual orientation, and Kenan says there was something almost “magical” about Baldwin’s frankness on the issue. At a time when major publishers wouldn’t consider taking on a book about homosexuality, Baldwin wrote his second novel, Giovanni’s Room, about a love affair between two white men.

“Right out of the box, Baldwin was going to blaze his own path,” Kenan says. “And he got away with it. It’s hard to imagine how he did — part of it was his charisma, his rhetoric … A lot of people would have had the door slammed in their face.”

Underneath The Veil

The collection includes a dramatic profile of the boxer Sonny Liston on the night of his historic 1962 showdown with Floyd Patterson. Though publicly Liston was known for being a criminal connected to the mob, Baldwin found him to be a “gentle teddy bear.”

Kenan believes Baldwin’s own background allowed him to see through the spin to get to know the man himself. He found Liston to be a “very complicated, very dedicated, and very spiritual” person.

Baldwin wrote that Liston reminded him of “big black men I have known who acquired the reputation of being tough in order to conceal the fact that they weren’t hard.”

For Kenan, the quote sums up the way Baldwin was so well-equipped to explore the complexity of black identity in America.

“There is a dichotomy between the way the world views a person and the way your folk see you,” he says. “I think that what we see in this piece is underneath that veil.”

‘An Insight Into Black America’

“You give me this advantage,” Baldwin once wrote to his white audience. “Whereas you never had to look at me — because you’ve sealed me away along with sin and hell and death — my life was in your hands and I had to look at you. I know more about you than you know about me.”

Kenan says that as members of the minority, African-Americans are observers of the majority culture — through television, newspapers and pop culture, blacks “are privy to so much about white folks’ lives” — but not vice versa.

Kenan points to Baldwin’s 1963 New Yorker profile of Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. “The Fire Next Time” turned into a “long peroration, a sermon about race,” Kenan says. “And it became a huge rallying point for black folk and white folk.”

During a tense time in America when blacks and whites didn’t have opportunities to communicate, Kenan says Baldwin’s writing gave them something to talk about. His descriptions of growing up poor and black and discriminated against helped open a window through which the majority could begin to truly see the minority.

“He lifts the veil,” Kenan says. “White people felt that they had an insight into black America that they didn’t have before.”

Read more at NPR