2 years ago, Sports Illustrated sat down with a group of African-American track and field athletes to discuss their encounters with racism. The conversation took place after the killing of George Floyd and these athletes prepared for the Summer Olympics the following year. This week we will share their experiences in their own words.

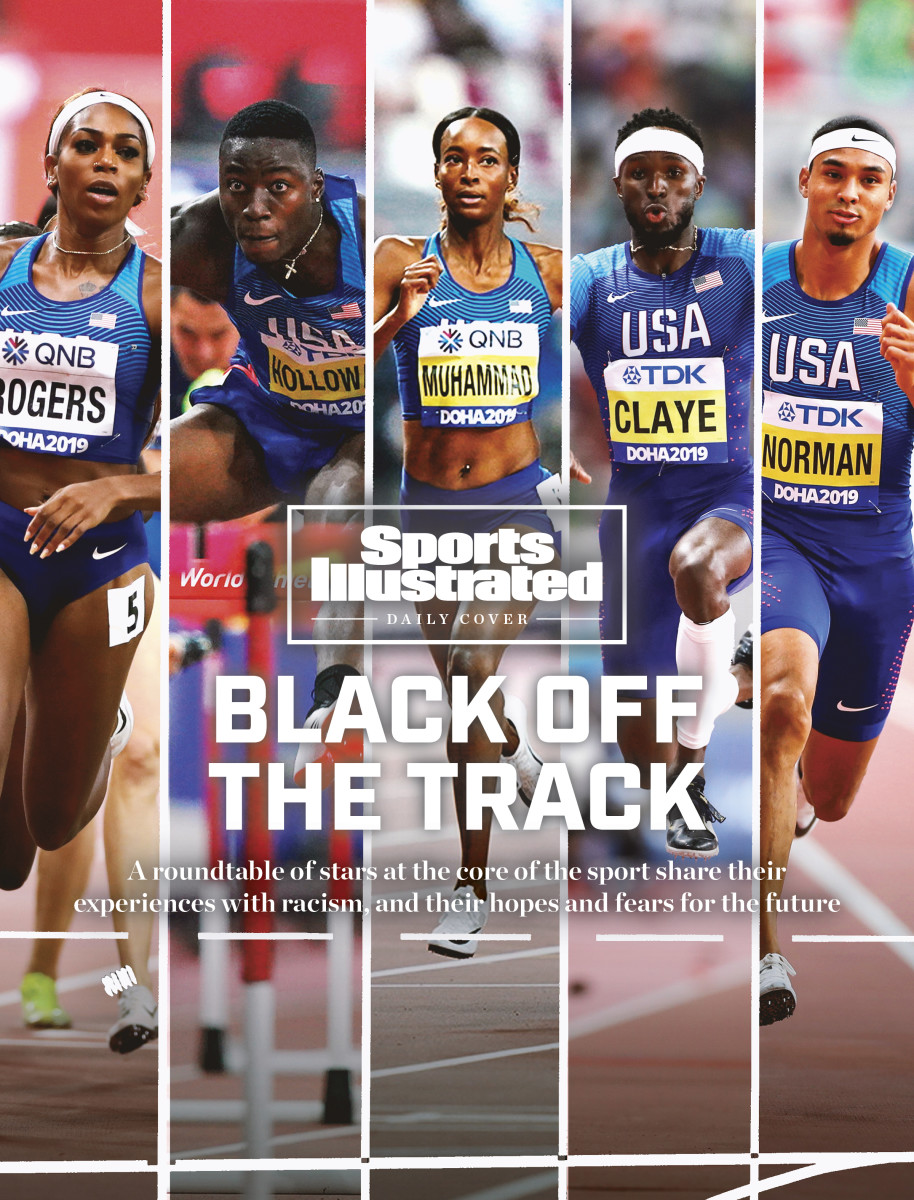

Black Off The Track: Track Athletes Share Their Encounters With Racism in America

A roundtable of stars at the core of the sport detail their experiences with racism, what it’s like to be Black in America and their hopes and fears for the future.

The violent killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer and the ensuing protests across the country have propelled nationwide activism and amplification of Black voices. Over the last week and a half, people have entered a period of self-reflection, reading, and talking and listening to the experiences of Black people in America. The conversations are new (and sometimes uncomfortable) and they are happening everywhere, including in a house of nine professional athletes training in Boulder, Colo., for next year’s Olympics.

“I’ve been able to share my experience, my fears and my hopes for the future with people who might not have had that conversation before,” says Aisha Praught-Leer, a middle distance runner who ran for the United States until 2015, when she switched to representing Jamaica. “Once that continues to grow, then we’ll have change, because Black people will have a voice in allies who want to change the dialogue and script for all Americans.”

There’s no question that Black track and field athletes are at the core of the sport and much of the reason why Team USA tops the medal table at global championships. But beyond stories of their successes as athletes, little has been shared or asked about their day-to-day life experiences and challenges when the color of their skin is seen as an obstacle.

Last week, SI reached out to 14 Black track and field athletes, asked a series of three questions and listened. The participants included:

• Dalilah Muhammad, 400-meter hurdles world record holder, Olympic champion and world championship gold medalist

• Will Claye, 6x world championship medalist, 3x Olympic medalist

• Michael Norman, 2021 Olympic 400 meter gold favorite

• Mohammed Ahmed, 2019 world championship 5000 meter bronze medalist

• Grant Holloway, 2019 world championship 110-meter hurdles gold medalist

• Aleec Harris, 2017 U.S. 110-meter hurdles champion

• Shamier Little, 2015 400-meter hurdles world championship silver medalist

• Marielle Hall, long distance runner and 2016 Olympian

• Rai Benjamin, 2019 400-meter hurdles world championship silver medalist

• Aisha Praught-Leer, 2018 Commonwealth Games steeplechase gold medalist

• Darrell Hill, 2016 Olympian, shot put

• Raevyn Rogers, 2019 world championship 800-meter silver medalist

• Jarrion Lawson, 2017 world championship long jump silver medalist

• Keturah Orji, 2016 U.S. Olympian and triple jump U.S. record holder

What was your first or most impactful experience with racism that has shaped you into the person you are today?

Dalilah Muhammad: In 2019, I remember the night before the 400-meter hurdles world championship final in Doha, someone said to me that I had to win the race. He wasn’t speaking to me on the track and field side of it, he just wanted to make sure I knew that coming in second place would be completely unmarketable for me. Sometimes in America, that’s how it feels. You either have to be the best or we’re not spoken about. Being in second place is not a luxury that we have.

There have been many times I’ve been told I might have this or that if I was white. It’s such a widely accepted view and reality that we face as Black athletes or Black women. Whether it’s true or not, because it’s such a widely accepted view, you can’t help but recognize it as true. Those experiences are so difficult.

Marielle Hall: There are things that happened when I was younger that I missed. I’ve been in elementary school classes where someone doesn’t want me to play with their crowns because I’m dirty. Someone told my sister that she was never going to get married because she was Black. You have these small run-ins with racism but when you’re younger, you have ignorance. You get into the world and think everything is equal. Because so many of those early experiences are with your family, everyone is kind of loving in that setting. You’re not callused to other people yet.

Now, you think about those moments where your mom comes storming into your classroom yelling at the teacher or calling up someone’s parents to tell them what a kid said. I remember being overwhelmed because I’m still in class and I still want friends, so I didn’t want to be isolated. My mom has always been very brash but now that I’m older, I recognize that she was being protective. You want your kids to have the best possible experience and to be themselves in the best way that they can. You’re protective of those experiences because they are so formative. If you internalize the things that people say to you at a young age, that will show up in how you feel about yourself in the world and what you think you can do.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/opinion/contributors/2020/10/29/canadian-olympian-10m-runner-mohammed-ahmed-shares-a-poem-observing-greatness-on-being-young-black-and-patient/mohammedahmed.jpg)

Mohammed Ahmed: During my time at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the Ferguson riots happened, and they had an indelible impact on how I thought about my interaction with the police. I’ve only been stopped by the police once.

In 2016, my teammates and I went back to Madison to do some heat and humidity training before the Olympics in Rio. We were staying in Middleton, which is 15 to 20 minutes outside of Madison. I asked if I could take the car to State Street and reminisce some of my old days. I went and dined at my favorite restaurant and walked around. When it was time to go back, I took a glimpse of Camp Randall Stadium and my old neighborhood from my five years in the city. I pulled over and slowly drove through my neighborhood for 10 minutes or so. Then, I got on the road and left.

Within one or two minutes of being on the road, sirens start blaring. There were a number of cars near me and I figured it was for something that happened somewhere so I pulled over. All of a sudden, I saw the police officer come up right behind me.

I couldn’t believe it. I wondered if I did something wrong, and Ferguson came to mind. I turned off the car, rolled down the window, put my hands up and didn’t say anything. I didn’t know how to interact with the police officer. I don’t think I was speeding but maybe I was five miles over the limit.

He asked me a number of questions, including, “What were you doing driving around that area?” So I determined he had been following me for at least 20 to 30 minutes. I felt like I had not broken any rules, but I remember I had trouble with the interaction—this was my first with an officer. At one point, he asked me if I was high or drunk. I said I wasn’t, but he said I seemed flustered.

I was reminded of Ferguson and I recalled in my mind what the police can do. He has a gun. That probably gave me anxiety and so I wasn’t able to speak or articulate as well as I could have. I was shocked to be pulled over like that, but I tried to compartmentalize things in a manner so nothing crazy would happen.

The experience that shaped me more than anything was being detained at the border. Visibly being a person of color, being Muslim, being a Somali and carrying a Muslim name—all of those identities went against me from a very young age. An Ethiopian Canadian poet named Boonaa Mohammed, who is also Muslim and Black, says in one of his poems, “I’m black and Muslim, everywhere I go someone hates me.”

For me, I’ve had that experience based on my name, based on the war on terror and what that created. I can’t even count the number of times that I’ve been sent to the extra screening room at an airport. There’s also my color. I relate with that line in the poem a lot. Despite all the things I’ve accomplished as an athlete, I have to confront those two realities.