Good Morning POU!

“Environmental racism” was a term coined in 1982 by Benjamin Chavis (pictured below), previous executive director of the United Church of Christ (UCC) Commission for Racial Justice.

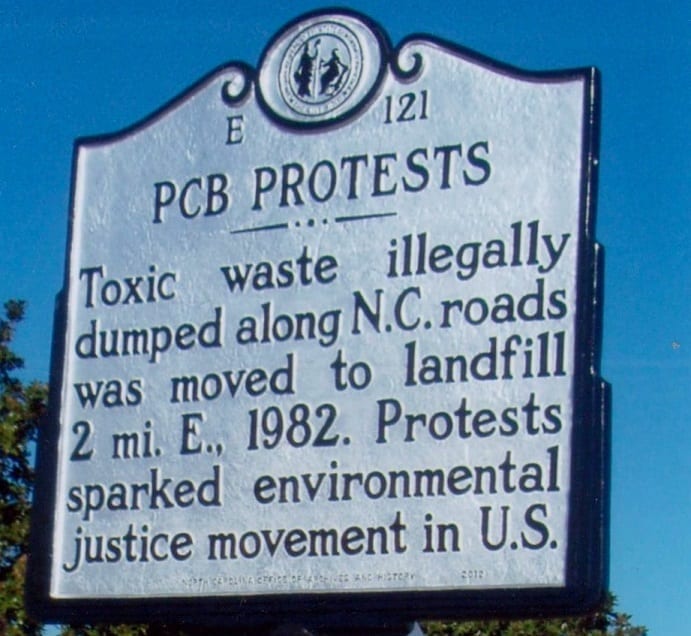

In a speech opposing the placement of hazardous polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) waste in the Warren County, North Carolina landfill, Chavis defined the term as:

racial discrimination in environmental policy making, the enforcement of regulations and laws, the deliberate targeting of communities of color for toxic waste facilities, the official sanctioning of the life-threatening presence of poisons and pollutants in our communities, and the history of excluding people of color from leadership of the ecology movements.

Recognition of environmental racism catalyzed the environmental justice movement that began in the 1970s and 1980s with influence from the earlier civil rights movement. Grassroots organizations and campaigns brought attention to environmental racism in policy making and emphasized the importance of minority input. While environmental racism has been historically tied to the environmental justice movement, throughout the years the term has been increasingly disassociated. Following the events in Warren County, the UCC and US General Accounting Office released reports showing that hazardous waste sites were disproportionately located in poor minority neighborhoods. Chavis and Dr. Robert D. Bullard pointed out institutionalized racism stemming from government and corporate policies that led to environmental racism. These racist practices included redlining, zoning, and colorblind adaptation planning. Residents experienced environmental racism due to their low socioeconomic status, and lack of political representation and mobility. Expanding the definition in “The Legacy of American Apartheid and Environmental Racism”, Dr. Bullard said that environmental racism:

refers to any policy, practice, or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (whether intended or unintended) individuals, groups, or communities based on race or color.

The Warren County PCB Landfill Case

Warren County PCB Landfill was a PCB landfill located in Warren County, North Carolina, near the community of Afton south of Warrenton. The landfill was created in 1982 by the State of North Carolina as a place to dump contaminated soil as result of an illegal PCB dumping incident. The site, which is about 150 acres, was extremely controversial and led to years of lawsuits. Warren County was one of the first cases of environmental justice in the United States and set a legal precedent for other environmental justice cases.

Beginning with Governor Hunt’s administration’s December 20, 1978, announcement that “public sentiment would not deter the state from burying the PCBs in Warren County,” the PCB landfill was surrounded by controversy. The landfill was located in rural Warren County, which was primarily African American. Warren County has about 18,000 people living in the county. Sixty-nine percent of the residents are non-white, and twenty percent of the residents live below the federal poverty level. The county has been determined as a Tier I county for economic development. The residence of the poor and predominantly African-American Warren County, North Carolina opposed the development there of a landfill designed to contain large quantities of soil contaminated with PCBs. Although the coalition lost the battle to stop the landfill, the protesters obtained numerous concessions from the state over the years. The state claimed that the Warren County site was the best available site; however, the site selection process was not based on scientific criteria — soil permeability properties or the distance to groundwater — but on other, less tangible criteria, including the demographics of the county. EPA and state officials claimed they could compensate for improper soil qualities and the close proximity to groundwater with the engineering design of their “state-of-the-art”, “dry-tomb”, zero-percent discharge landfill.

An article from 1996 said, “North Carolina’s PCB landfill in Warren County leaks about a half an inch of water a year”. State data on rainfall during 1996 and water levels inside the dump indicate 30,000 gallons of water flow into the site each year and 26,000 gallons flow out. During this time it is said that citizens and some members of the working group urge Governor Hunt to clean up the dump and detoxify the PCB contaminated soil. The PCBs came from dirt roads in the state where the chemical was dumped illegally in the 70s.

After four years, Warren County citizens officially launched the environmental justice movement as they lay in front of 10,000 truckloads of contaminated PCB soil. During the six-week trucking opposition, with collective nonviolent direct action, which included over 550 arrests, Warren County citizens mounted what the Duke Chronicle described as “the largest civil disobedience in the South since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., marched through Alabama.” It was the first time in American history that citizens were jailed for trying to stop a landfill, from attempting to prevent pollution. In an editorial titled “Dumping on the Poor,” The Washington Post described Warren County’s PCB protest movement as “the marriage of environmentalism with civil rights,” and in its 1994 Environmental Equity Draft, the EPA described the PCB protest movement as “the watershed event that led to the environmental equity movement of the 1980’s.” With public pressure mounting, Governor Hunt then pledged to Warren citizens that when technology became available, the state would detoxify the PCB landfill. The resulting controversy led to the coining of the phrase “environmental racism” and galvanized the environmental justice movement.

Soon after, academics and scholars began research and case studies to provide further evidence linking poor in minority neighborhoods across the country with a higher level of environmental hazards. The Warren County protest led the commission of racial justice to produce “Toxic Waste and Race”, the first national study to correlate waste facilities sites and demographic characteristics. Race was found to be the most potent variable in predicting where these facilities were located; more powerful than poverty, land values, and home ownership.