Good Morning POU!

I’ve heard this question so many times, and I’ve asked it myself. I never knew there was a origin to it, now I know.

“Who are your people?”

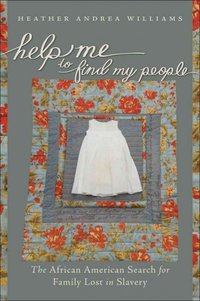

It’s a question exchanged often by black Southerners to identify kith and kin. But few remember that its roots can be traced to the aftermath of the Civil War. Once emancipated, former slaves desperately searched for family members who had been sold away from them. Their plaintive entreaty — “Help me to find my people” — provides the title and the subject of an important historical book by Heather Andrea Williams.

After the Civil War, African Americans placed poignant “information wanted” advertisements in newspapers, searching for missing family members. Inspired by the power of these ads, Heather Andrea Williams uses slave narratives, letters, interviews, public records, and diaries to guide readers back to devastating moments of family separation during slavery when people were sold away from parents, siblings, spouses, and children. Williams explores the heartbreaking stories of separation and the long, usually unsuccessful journeys toward reunification. Examining the interior lives of the enslaved and freed people as they tried to come to terms with great loss, Williams grounds their grief, fear, anger, longing, frustration, and hope in the history of American slavery and the domestic slave trade.Williams follows those who were separated, chronicles their searches, and documents the rare experience of reunion. She also explores the sympathy, indifference, hostility, or empathy expressed by whites about sundered black families. Williams shows how searches for family members in the post-Civil War era continue to reverberate in African American culture in the ongoing search for family history and connection across generations.

Excerpt: Help Me To Find My People

It is not possible to even begin to estimate how many people acted on their hope and searched for family members or sent messages or received news through the grapevines that stretched from Canada to Texas, from Boston to California, and frayed under the strain of the distance and the silence. Some people, unable to cope with the dissonance of caring for someone who might already be dead and, in any event, would not likely return, surely erased loved ones from their memories. But others carried the memories with them as they went about the labor of slavery, passed through the hands of one owner to another, and created new families. They were slaves with few material resources and severely constricted mobility, yet some made efforts to search for their families. They had to be opportunistic, willing to seize any chance to make contact with a lost relative. And they had to be strategic, devising targeted appeals for help. When they were able, they sent out missives and messengers who might bring back the dead.

Sella Martin’s mother sent such a messenger to find her son. Martin, along with his mother, Winnie, and his older sister, had been sold to break up the relationship between Winnie and the white man who was the father of her two children. The three were taken to Georgia and sold to a man whom Martin referred to only as Dr. C. After some time, Dr. C’s gambling debts led to the seizure of his slaves, and Martin, still a young boy, was taken away from his mother and sister and became the property of a man who owned a hotel in Columbus, Georgia, frequented by gamblers. The young boys in the neighborhood adopted gambling as a pastime, and Martin traded his skills as a proficient marble player for reading lessons from a white boy. As he accumulated the money he won at marbles and funds he earned by reading to other enslaved people, Martin made a plan. “I was laying up my money,” he said, “to pay my traveling expenses in going to see my mother, and to purchase something to carry to her as proof of my love.” The problem was that he had no idea where his mother was.

One day Martin encountered a “coloured man from the country who had brought in a load of cotton.” The man was looking for Winnie’s son. “I trembled all over,” Martin recounted, “as I asked her son’s name, for I was sure he knew where my mother was. I stopped, and sat down on a stump to collect myself, and when I got the strength I told him who I was.” The man replied, “‘Winnie told me to give you dis ‘ere’; and he handed me a rag of cotton cloth, tied all about with a string. I opened it, and found some blue glass beads — beads given to my mother by her mother as a keepsake when she died. I knew,” Martin said, “by that token that he was a messenger from my mother, though of course my mother and myself had had no time to agree to any such thing before we were parted. But I had often heard her say that nothing would make her part from these beads.”

Sella Martin’s mother sent material objects loaded with history, sentiment, and significance to ensure that her son would recognize and respond to her messenger. The blue beads that she wrapped in cloth and tied all about with a string were much like the blue glass beads that enslaved people in New York City; Newton Cemetery, Barbados; Montpelier Plantation in Jamaica; and Parris Island, South Carolina, wore, carried, and sometimes buried in the graves of their loved ones. These particular beads held meaning to Winnie because they were keepsakes, a possession that her mother had prized enough to pass on to her. Now the daughter risked sending the treasured beads on the road with a man she hoped would use them to find her son. As they went about doing the work of slavery, some enslaved men experienced a degree of mobility. Taking messages for owners, picking up the mail at the post office, making deliveries, fetching the doctor, and transporting goods to market or to a storehouse, these men moved about the landscape and became couriers of information able to deliver news and messages from enslaved people to friends and relatives, thereby establishing a physical connection between them. Winnie knew that this man who was a part of her community would travel within miles of the place where she had last seen her son, and she enlisted his help.

Martin spent more than a year gathering the courage to run away to find his mother, but eventually, as many other African Americans did, he took to the roads. All who did so assumed great risks; they might be caught by patrollers and beaten and sold by their owners, or they might be caught and sold by strangers. Their experiences constitute the backstories of the ads that owners placed in newspapers offering rewards for escaped slaves. They had no road maps, few were familiar with areas beyond a few miles of their homes, and they moved about amidst the presumption that every black person belonged to someone and had to account for his or her movements. Martin was more prepared than others. He now had a good sense of where his mother lived, and he was literate. He wrote a pass for himself, took pen and ink with him in case he could convince his mother to run away too, and set out to walk the sixty miles to her plantation. It took three nights to reach her.

His mother said that in the year since she had found out where he lived, she had run away three times, intending to make her way to him in Columbus. Each time she had been captured and beaten, leaving “terrible furrows made by the cow-hide” on her back. Martin could not convince her to try escaping one more time. She had lost her nerve. “I have borne a great deal in my life,” she told her son, “so much that my spirit is crushed and all courage is gone from me, and my body is worn out with labour and the lash.” She believed it would not be long before she died, and as she despaired of ever living with her children again on earth, she welcomed the prospect of death. “There is no hope of our ever being together on earth,” Martin recalled his mother saying, “and therefore, the sooner I start on my journey to heaven the sooner will my misery from our separation and from slavery cease.” Their reunion was short-lived; mother and son were still slaves, after all. Winnie’s owner caught Martin and returned him to his owner, who soon sold him. For a long time both Sella Martin and his mother had held on to hope that they would see each other again. Martin made plans, but his mother acted, first sending her messenger, then attempting to run away. But now her hope had been transformed into despair. The beads had served as a code between mother and son, representing their ties to each other and to a family history, but all they had remaining was his mother’s faith that they would meet again in heaven.

From Help Me To Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery by Heather Andrea Williams. Copyright 2012 by the University of North Carolina Press. Excerpted by permission of University of North Carolina Press.