Good Mornng POU! We continue our look at former members of the Black Panther Party that are serving decades long prison sentences for crimes they more than likely did not commit. Today’s entry is taken from a 2016 article in the Lincoln Journal Star (Nebraska).

After 45 years in prison, question remains: Cop killer or political prisoner?

Each year, fewer people alive know firsthand who was behind the explosion in a vacant house in North Omaha that killed a young cop before dawn on Aug. 17, 1970.

Did Ed Poindexter and David Rice send a teenager to deliver a suitcase bomb and make the 911 call that sent patrolman Larry Minard and seven other officers into a trap?

Did someone plant 14 sticks of dynamite found in Rice’s basement, and did investigators turn the screws on 15-year-old Duane Peak to get him to connect the two men to the crime?

Tracked down years later living in another state under a new name, Peak told Sen. Ernie Chambers that he feared dying in the electric chair, but he stuck to his claim that no one forced him to say what he did. He said he told the truth at the trial.

This spring, Rice, who had taken the name Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa, died in the infirmary at the Nebraska State Penitentiary, denying until the end that he had anything to do with Minard’s death.

Poindexter, now more than 45 years into a life sentence, continues to claim his innocence as well, despite knowing that a show of remorse might help his chances at being set free.

Barring new evidence, which seems a long shot, the 72-year-old is not likely to go anywhere.

Many people, including the global human rights organization Amnesty International, believe the two were political prisoners, easy targets for police because of their ties to the Black Panther Party during a turbulent time.

Poindexter grew frustrated at the racism he saw when he served in the Vietnam War and when he got home. He turned to the party and wrote of taking up arms against police. “I have some regrets about it. But it can’t be undone now,” Poindexter said in a visiting-room interview at the penitentiary late this summer.

But first things first. Rewind to 1970.

The headline on the front page of The Lincoln Star on Tuesday, Aug. 18, 1970: “OMAHA OFFICER KILLED … Anger, Despair Grip Policemen.” The above-the-fold photo showed investigators sifting through debris for clues.

The booby-trapped suitcase exploded in Minard’s face while he checked the vacant house for a woman said to be screaming for help, according to an anonymous 911 call. The married father of five would have turned 30 three days later.

The blast knocked another officer out of the room, crumpled the one-story frame house and knocked down officers standing outside.

Omaha had become the latest blip on the radar during a time in which police and protesters clashed over the civil rights movement and Vietnam War. Alabama state troopers unleashed billy clubs and tear gas on black voting activists. Deadly riots broke out after Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down in Memphis and Ohio National Guardsmen killed four Kent State students during an anti-war protest.

In 1969, a white police officer called to a robbery in North Omaha shot Vivian Strong, a 14-year-old black girl, in the back of the head. Her crime: dancing at a party in a vacant apartment in the projects and running when the cops came. Her death sparked riots.

The Black Panthers had taken up arms to protect black neighborhoods from police brutality and got into shootouts across the country while the FBI worked quietly behind the scenes to dismantle it.

When the bomb killed Minard, Rice and Poindexter, then leaders of the National Committee to Combat Fascism, made perfect suspects. In the months before the explosion, they’d had bylines in newsletters expressing hatred for police and advocating violent, even lethal force, against them.

“They were Black Panthers, and a police officer died,” said Mary Dickinson of Lincoln, who was in high school in South Omaha then.

Even then, she said, she knew “this isn’t right.”

But the group’s headquarters was just two blocks away, and a month earlier the ATF had gotten a warrant to search it for dynamite and machine guns on the word of 12-year-old Marialice Clark, who later vanished. The search never happened.

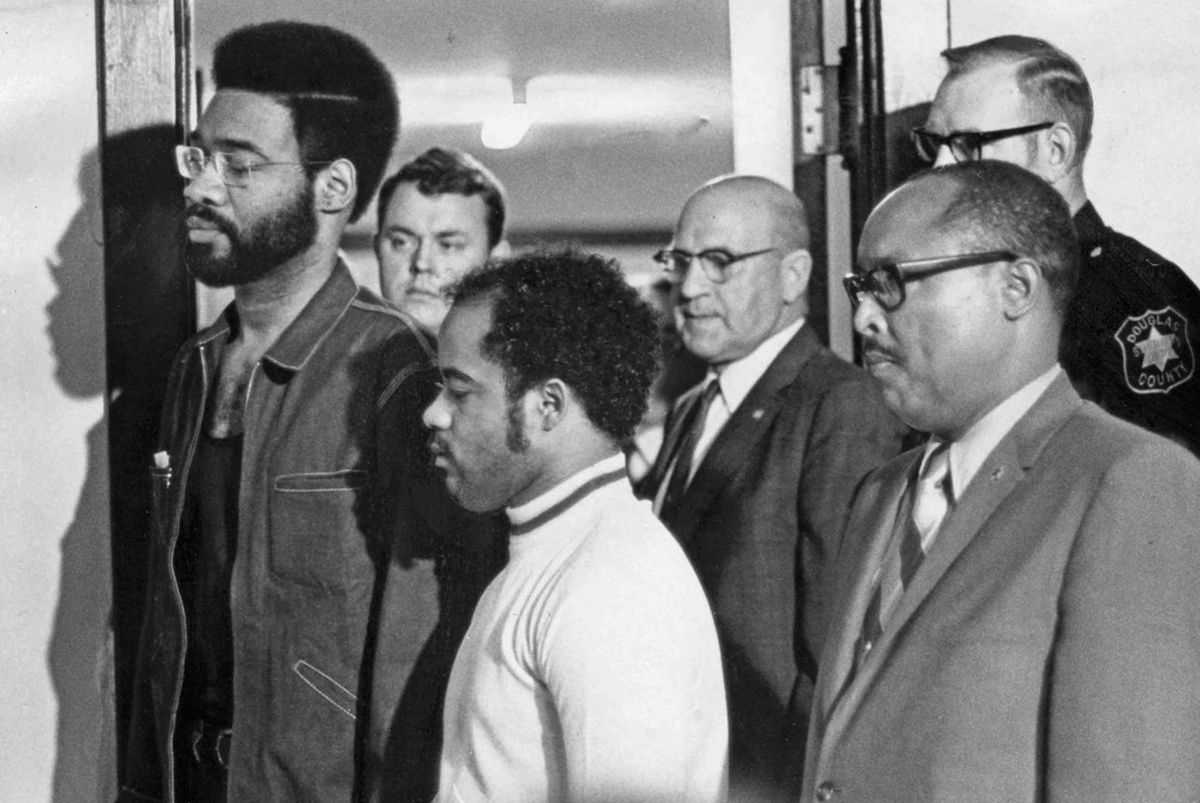

Omaha police began rounding up people who knew Rice and Poindexter and, before long, had warrants to arrest them and the young Duane Peak. What exactly the judge signed off on isn’t clear because the documents no longer exist, according to a later court opinion.

With little more to go on than Rice’s reputation as a black militant, police searched his house.

“We have been told in the past that Rice keeps explosives, at his residence, and also illegal weapons, which he has said should be used against police officers,” an officer wrote in the affidavit to get the warrant.

It wouldn’t be enough to get a search warrant today, but on Aug. 22, 1970, police went into 2816 Parker St. and left with 14 sticks of DuPont Red Cross brand dynamite, blasting caps, wiring, a battery and a pair of long-nosed pliers.

Soon after, they arrested Poindexter at his mom’s house at 3415 N. 25th St.

He remembers being upstairs washing up for a dinner of his mom’s beef stew when she called up and told him to look out the window. Cop cars were cruising up the block. Before he got downstairs, they were at the door. Holding his niece, his mom told them if they hurt him they were going to have to shoot her and a baby first.

“The rest is history, as they say,” Poindexter said.

Rice turned himself in to police on Aug. 27, 1970.

The case

From the beginning, both men said they’d been framed, that Peak was lying and the dynamite was planted.

Their trial started on April Fool’s Day 1971.

A chemist who analyzed their clothes found traces of dynamite in Poindexter’s jacket pocket and on Rice’s pants. Defense attorneys later would say the same particles could have come from matches. Another expert testified the pliers from Rice’s basement had been used to cut copper wire like that used in the bomb.

But the key witness for the state was Peak, by then 16.

At a pretrial hearing, he refused to say either was involved, then returned to the stand later with puffy eyes and said they were.

Chambers, not yet a state senator, was in the courtroom that day and felt sure Peak had been roughed up in between. Years later, Peak denied that he was.

He had given lots of stories about the bomb and how he got it. But at trial, over the course of two days, Peak said that a week before the bomb went off Poindexter told him “he had a beautiful plan to blow up a pig.” That same night, Peak said, he got a suitcase from someone else in the group and took it to Rice’s house. There were sticks of dynamite already inside.

Peak said he watched Poindexter make the bomb, then went with him the next night to see the vacant house on Ohio Street.

On the night of Aug. 16, 1970, Peak told the jury, he went back to Rice’s house to get the suitcase and the tacks he needed to arm it, then took a meandering path to 2867 Ohio St. and called 911.

The jury deliberated for 25 hours before finding Poindexter, 26, and Rice, 23, guilty on April 17, 1971. The nine women and three men gave them life sentences, not the death penalty the county attorney sought.

In the 45 years since, state courts affirmed their convictions, federal courts granted we Langa a new trial right up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reversed it. In the ’90s, the Nebraska Board of Parole recommended their sentences be commuted to a definite term of years, which would have made them eligible for parole at some point, but the state Pardons Board refused to give them hearings.

Lincoln attorney Bob Bartle, who represented Poindexter for years, found a raft of issues to challenge. Among the biggest:

* The 911 recording, which surfaced in the 1980s. Prosecutors hadn’t given it to trial attorneys, who could’ve played it for the jury. They tracked down Peak to record his voice and a voice identification expert compared it to the call and testified he was almost certain it wasn’t Peak’s voice.

* Inconsistent testimony from the officer who said he found the dynamite in Rice’s basement and the prosecutor’s failure to disclose that the same officer had arrested three men with 40 sticks of the same kind of dynamite in their car three weeks earlier. Prosecutors dropped charges against them four days after Rice and Poindexter were found guilty.

None of the issues was enough to get Poindexter a new trial.

Daughter: Appeals are hell

Minard’s daughter, Carol Booher, who was 11 when he was killed, notes that supporters of Rice and Poindexter have picked apart evidence for years, checked every angle and found nothing.

In 2006, she went to Poindexter’s post-conviction hearing. She never wanted to have to look him in the face, she said, but she did that day — and it was hard.

“I’m almost 60 years old and it still breaks my heart,” Booher said in a call from Florida.

Continued appeals put the family through hell, she said. “I’m sure the cops didn’t do everything exactly by the book,” she said, adding that cops sometimes make mistakes and her dad had a lot of friends on the force. “But I don’t think it was anything that would’ve changed the outcome of the trial.”

“This changed all of our lives,” she said.

She said she thought Rice’s death would bring her some peace or closure. It didn’t. “He died in prison where he needed to die,” Booher said.

Her sister Charlotte Hyland still lives in Nebraska and said she has forgiven them. “But do I believe they are both guilty? Without a doubt,” she said. “Now, all I can do is pray that he (Poindexter) stays where he is, and trust in my Lord,” she said.

At this point, Bartle said, it would take compelling new evidence that someone else is responsible for Minard’s death.

“There’s not a whole lot of legal options left.”

Or, he said, the Nebraska Pardons Board could commute his sentence, something rarely done and only when an inmate has expressed remorse for his crime.

“Their position all along has been, ‘We are political prisoners,'” said Bartle.

Because a police officer was killed, it’s tough to convince people the two were framed, said Tariq Al-Amin, a 25-year Omaha cop who retired 10 years ago.

He wasn’t living in Omaha when the bomb exploded but has studied the case for years and talked to other black officers who were with the department at the time and felt Poindexter and Rice were just two guys investigators thought needed to be taken off the street.

“This was coming from a lot of officers I respected,” Al-Amin said.

It would’ve been an easy set-up, he said, and he has seen from the inside what police were willing to do to protect their own.

“I believe some of those retired cops who worked the case know, but it’s something they’ll take to their grave,” Al-Amin said. “I would like to make an appeal to anyone who knows anything to please come forward.”

Asked why Peak would continue to lie all these years later if he’d sent two innocent men to prison, he said he thinks Peak always was protecting his family.

Even if Peak came forward now and changed his story, Al-Amin said he doesn’t know how much weight the court would give it.

To Poindexter, it comes down to this: “There’s still another murderer out there.”

Life in prison

Poindexter went before the Parole Board in 1972 and again in 2013. The last time, he tried to make the case that his sentence should have expired in 1988. Lifers of his generation historically served 18 to 20 years, he argued. The argument went nowhere.

He’ll be 79 when he comes up for parole again in 2024.

“What they do is they just keep you in forever,” Poindexter said.

He recalls being outraged when he heard a lifer say back in 1974 that he wished he’d asked for a death sentence.

“Had I known then that I was gonna be down this long I woulda asked for it,” Poindexter said.

Today, fewer people may recognize his and we Langa’s names. But for years they were known in certain circles around the world, with big-name supporters behind them, like Angela Davis, Amnesty International and actor Danny Glover.

Many have come and gone, but one group, Nebraskans for Justice, still works for Poindexter’s release.

“A lot of people get frustrated and give up, and their voices are no longer heard. They don’t know what else they can do,” he said.

“I know I’m going to be out of here one of these days.”

Friends said we Langa wasn’t interested in compassionate release even though he suffered from a chronic lung disease. He wanted to be exonerated.

“I feel the same way,” Poindexter said. “But out is out.”

One day this fall, he blacked out while eating breakfast. It wasn’t anything serious, he said, just anemia.

“Yeah, man. I’m getting old,” said Poindexter, who turned 72 on Nov. 1.

On March 11, the day his old friend died, Poindexter got permission to see him in the prison hospital. We Langa, usually busy behind a typewriter, was unconscious but breathing. Poindexter remembers his palms were dry and warm.

“When I got there the room was full of people,” he said.

Just two weeks earlier, we Langa had mailed out a poem he’d written, “When it Gets to This Point,” about recent deaths of unarmed black men around the country that sparked protests.

Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice.

“And after a while the pictures, the names, the circumstances run together like so much colored laundry in the wash that bleeds on whites,” he wrote.

“My memory is too encumbered with the names of so many before and since.”

This summer, East African artist Emma Maasai carried out we Langa’s wishes and scattered his ashes at the top of Mount Kilimanjaro.

“We know that he was in prison for many, many years. And he died in prison. So we honor him and symbolically give him the freedom he deserved,” Maasai said before he sent ashes into the wind.

What’s next?

In a letter to the Journal Star, Poindexter said he misses we Langa but that his comrade’s passing hasn’t dampened his spirit.

“In fact, it has energized me to play a more active role in my own defense,” he said. “When Mondo was with us, I was known as the quiet one. … From here on out, I’ll do my best to be heard loud and clear.”

Poindexter recalled how they met in December 1969. He was walking on Lake Street, just off 24th past a fire house converted into a dance hall, and heard blues spilling out into the streets.

Poindexter introduced himself during a break, and they chatted. He told Rice about a Black Panther meeting he’d gone to the day before.

They hit it off right away.

“I’ll never have another friend like him,” Poindexter said.

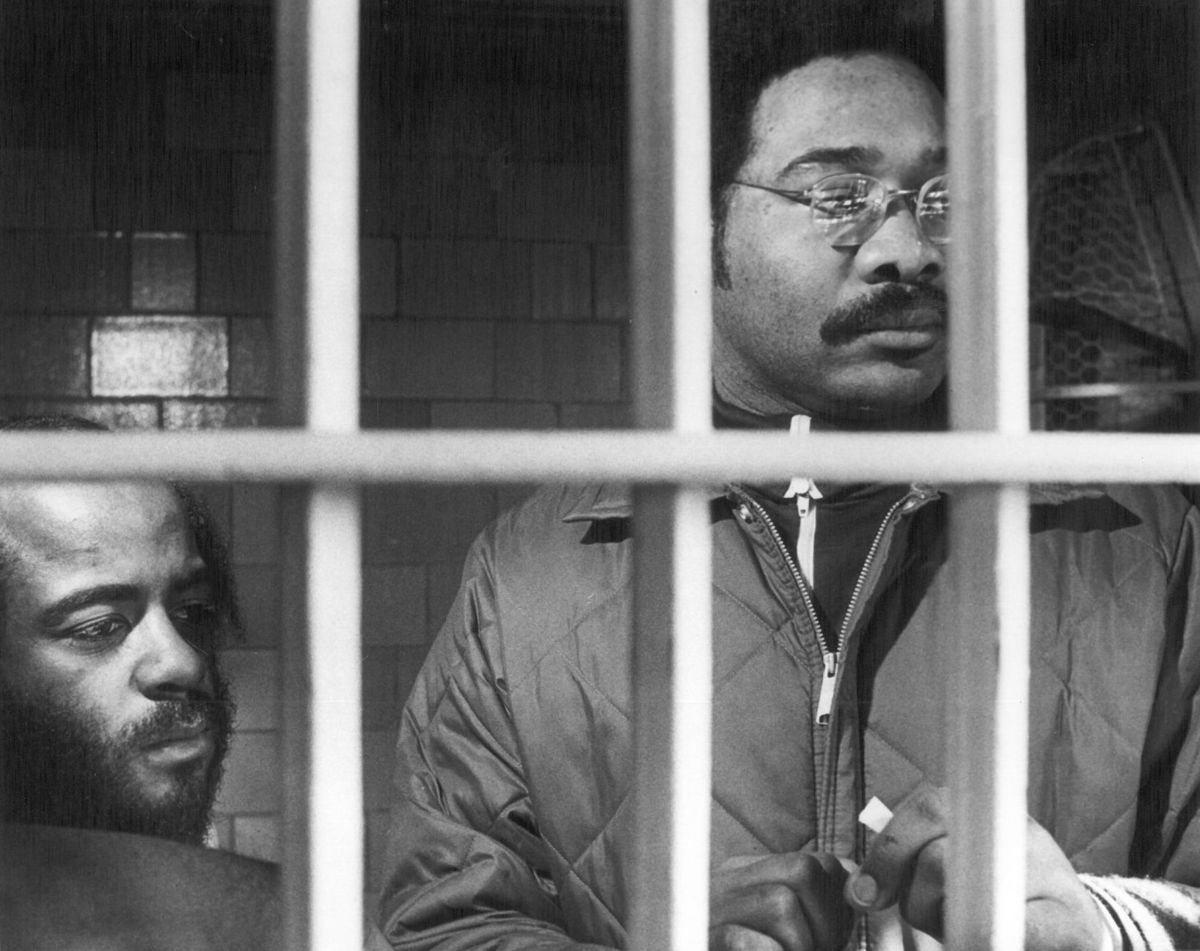

The friends in 2006.

The friends in 2006.

He served about half of his time in Minnesota, taking classes toward a master’s degree and developing a motivational program, but returned to Nebraska in 2006. For the past few years, he was in Cell 9 in a part of the prison reserved for older inmates, right around the corner from we Langa in 14.

Poindexter talks now about what he’ll do when he gets out, not if he gets out.

“I just keep focused on the future. Eye on the prize,” he said.

A born-again Christian since 2010, he said that’s what keeps him going. Even if, in the next breath, he talks about how his appeals are about done. Poindexter said he’s made it official: He wants his ashes spread in his old North 24th Street neighborhood in Omaha, the projects of his youth.

“I wish I could go back there,” he said.

Asked if he would say he is guilty if it meant he could get out, he said he would just be making a fool of himself.

“It’s all about the truth with me. Regardless of the consequences.”