Seneca Village was a small but vibrant community founded in 1825 by free African-Americans in uptown Manhattan. The area from West 82nd to 88th Streets between Seventh and Eighth Avenues was still farmland back then, a good six miles north of teeming downtown. The rural location had the marked advantage of offering working class African-Americans access to fresh air, space, and land, land that they could build homes on and cultivate to support their families.

When Andrew William bought the first three lots of land that would become Seneca Village on September 27, 1825, slavery was still legal in New York. Legislation passed in 1799 determined that enslaved people in the state would be emancipated on July 4, 1827., Andrew William paid John and Elizabeth Whitehead $125 for those three lots he purchased.

By 1850, black Seneca Village residents were 39 times more likely to own property than any other African-Americans in New York City. Andrew William wasn’t the only one to buy from the Whiteheads on September 27, 1825. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church bought six lots near 86th Street to use as a cemetery. One of the AME Zion Church trustees, Epiphany Davis, bought 12 lots for her own use, and a little community was born.

The village grew steadily from then on as black people moved out of lower Manhattan or migrated to the city from Virginia, Maryland, Connecticut, and New Jersey. The Whiteheads sold at least another 24 lots to African-Americans over the next 10 years. Black people weren’t the only ones to feel the lure of Seneca Village. In the 1840s, Irish and German immigrants joined the community. By 1855, census and property records put the population of the village at 264, 30 percent of them European, predominantly Irish.

By all accounts, the diverse community got along peacefully. Black and white worshipped together at the All Angels’ Church and were buried together in its cemetery. The one village midwife, Margaret Geery, delivered African-American babies and Irish and German babies alike.

As the population of Manhattan swelled—between 1821 and 1855 the population quadrupled—and the city expanded northward, rural land that had once been considered hinterlands started to feel the pressure. By the 1840s, the city was so crowded that people went to cemeteries like Green-Wood in Brooklyn for picnics and carriage rides. Prominent figures argued that New York City needed a public park like London’s Hyde Park. Privileged New Yorkers, keen for a congenial setting to drive their carriages and cut their fine figures, very much agreed.

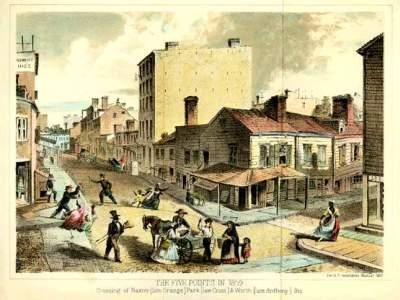

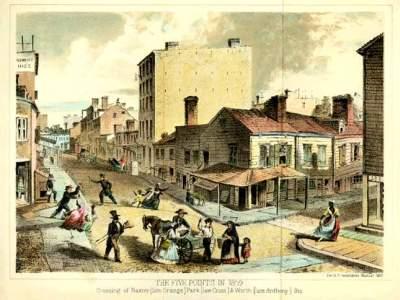

The newspapers advocating the new park smeared Seneca Village as a “shantytown” inhabited by “wretched and debased” “squatters.” The fact that they had owned their property and homes for decades made no difference. How could a working class enclave possibly compete with the prospect of a beautiful landscaped urban Eden?

The newspapers advocating the new park smeared Seneca Village as a “shantytown” inhabited by “wretched and debased” “squatters.” The fact that they had owned their property and homes for decades made no difference. How could a working class enclave possibly compete with the prospect of a beautiful landscaped urban Eden?

In 1853, the New York legislature picked a spot—700 acres from 59th to 106th Streets between Fifth and Eighth Avenues—and authorized the taking of the land by eminent domain. They set aside $5 million to buy the land from its current owners, approximately 1600 people over 7500 lots, just under 300 of them in Seneca Village. The property owners fought the law. For two years they petitioned the court and appealed decisions trying to save their homes, churches, school, cemeteries, their lives as they knew them. The law won.

In the summer of 1856, Mayor Fernando Wood sent the residents of Seneca Village a final notice, and in 1857 he sent the police to bludgeon them out. According to one newspaper, the violent clearing of Seneca Village was a glorious victory that would “not be forgotten [as] many a brilliant and stirring fight was had during the campaign. But the supremacy of the law was upheld by the policeman’s bludgeons.” On October 1, 1857, the city government announced that the land was free of pesky human habitation. The dwellings were demolished and Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux began to build Central Park.