Good Morning POU!

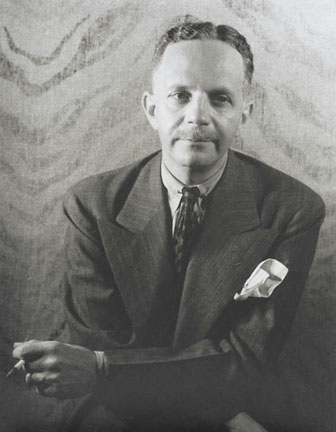

Today’s feature is a former head of the NAACP. Walter White used his light complexion to investigate lynchings by posing as a white man in the dangerous Jim Crow South. His actions, if discovered by anyone at these murderous events, would have led to his own immediate and brutal demise.

Walter Francis White (July 1, 1893 – March 21, 1955) was an American civil rights activist who led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for almost a quarter of a century and directed a broad program of legal challenges to segregation and disfranchisement. He was also a journalist, novelist, and essayist. He graduated in 1916 from Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), a historically black college

In 1918 he joined the small national staff of the NAACP in New York at the invitation of James Weldon Johnson. He acted as Johnson’s assistant national secretary and traveled to the South to investigate.

Within a few weeks of joining the national office of the NAACP a report came in about the lynching of Jim McIlherron in Estell Springs, Tennessee. Walter white volunteered to use his light complexion and blues eyes to investigate that lynching posing as a white man. He wrote afterwards,

“Like most boastful people who practice direct action when it involves no personal risk, [lynchers] just can’t help talk about their deeds to any person who manifests even the slightest interest in them. Most lynchings take place in small towns and rural regions where the natives know practically nothing of what is going on outside their own immediate neighborhoods.

In any American village, North or South, East or West, there is no problem which cannot be solved in half an hour by the morons who lounge about the village store”

He wrote an article about this lynching for The Crisis magazine. He would go on to investigate more lynchings or mob violence and write about them in popular magazines.

White used his appearance to increase his effectiveness in conducting investigations of lynchings and race riots in the South. He could “pass” and talk to whites, but also identified as black and could talk to members of the African-American community. Such work was dangerous. “Through 1927 White would investigate 41 lynchings, 8 race riots, and two cases of widespread peonage, risking his life repeatedly in the backwaters of Florida, the piney woods of Georgia, and in the cotton fields of Arkansas.”

In his autobiography, A Man Called White, he dedicates an entire chapter to a time when he almost joined the Ku Klux Klan undercover. White became a master of incognito investigating. He started with a letter from a friend that recruited new members of the KKK. After correspondence between him and Edward Young Clark, leader of the KKK, Clark clearly tried to interest White in joining. Invited to Atlanta, to meet with other Klan leaders, White declined, fearing that he would be at risk of his life if his true identity were discovered.White used this access to Klan leaders to further his investigation into the “sinister and illegal conspiracy against human and civil rights which the Klan was concocting.” After deeper inquiries into White’s life, Clark stopped sending signed letters; White was threatened by anonymous letters stating his life would be in danger if he ever divulged any of the confidential information he had received. By this time, White had already turned the information over to the US Department of Justice and New York Police Department. He believed that undermining the hold of mob violence would be crucial to his cause.

He first investigated the October 1919 riot in Elaine, Arkansas, where white vigilantes and Federal troops in Phillips County killed more than 200 black sharecroppers. The case had both labor and racial issues. Black sharecroppers were meeting on issues related to organizing with an agrarian union, which whites were attempting to suppress. They had established guards because of the threat, and a white man was killed. The white militias had come to the town and hunted down blacks in retaliation for that death and to suppress the labor movement.

Granted press credentials from the Chicago Daily News, White gained an interview with Arkansas Governor Charles Hillman Brough, who would not have met with him as the NAACP representative. Brough gave White a letter of recommendation to help him meet people, and his autographed photograph.

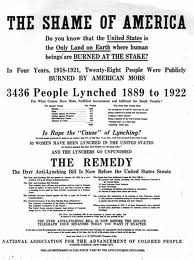

Walter White used his investigations to push fo federal anti-lynching bills, which were unable to get past the Southern Democratic block in the Senate. One of White’s many surveys within his undercover work showed that 46 of 50 lynchings during the first six months of 1919 were black victims, 10 of whom were burned at the stake. After the Chicago Race Riot of 1919, White concluded the causes of such violence were not rape of a white woman by a black man, as was often rumored, but rather the result of “prejudice and economic competition.” This was also the conclusion of a Chicago city commission that investigated the 1919 rioting; it noted specifically that ethnic in South Chicago, who were considered highly political and strongly territorial against other groups, including more recent European immigrants, had led the anti-black attacks.

In the late 1910s, newspapers reported a decreasing number of southern lynchings but postwar violence in Northern and Midwestern cities increased under the competition for work and housing by returning veterans, immigrants and African American migrants. In the Great Migration, hundreds of thousands of blacks were leaving the South for jobs in the North. The Pennsylvania Railroad recruited thousands of workers from Florida alone.

Rural violence also continued. Walter White investigated violence in 1918 in Lowndes and Brooks counties, Georgia; the worst case was when “a pregnant black woman [was] tied to a tree and burned alive after which (the mob) split her open, and her child, still alive, was thrown to the ground and stomped by some of the members”.

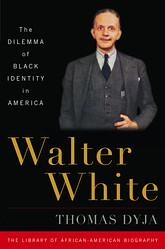

Below, an excerpt from “Walter White: The Dilemma of Black Identity in America” by Thomas Dyja.

Chapter Three: Undercover Against Lynching

On the morning of February 13, 1918, White and Johnson headed to the office, bundled up against another chilly day in New York. The winter so far throughout much of the United States had been dark and cold, and a coal shortage had forced President Wilson to shut down certain industries to conserve supplies. In the twelve days White had been up north, he’d rarely strayed far from Johnson, going to work together, taking lunch with him at the Automat, then stealing a few minutes at Brentano’s where the older man had him on a crash course in the sort of modern literature not taught at Atlanta University. The day before had been Lincoln’s Birthday, as well as the ninth buy pfizer viagra 50mg anniversary of “The Call.” But the paper they shared on the train downtown showed how little progress had been made since then: In a Tennessee hamlet halfway between Franklin, the birthplace of the Klan, and Sewanee, the height of Southern academe, a black farmer named Jim McIlherron had been burned alive for shooting two white youths. Few other details were forthcoming.

At the NAACP office the ugly symbolism of a Lincoln’s Birthday lynching made the usual telegrams of protest to the governor and president feel limp. As John Shillady went ahead and sent them anyway, suddenly White had an idea. What if he went to Estell Springs, site of the murder, pretending to be white, and got the details himself?

Johnson and Ovington had reservations, to say the least. Other African Americans had personally investigated lynchings before, Ida Wells-Barnett most notably, but never in this way. A black man caught passing in order to spy on whites would be lynched himself. Period. White knew that as well as anyone, but twenty-four years old, straight out of Georgia, looking, as the poet Langston Hughes would describe him, like a “little Irishman,” he kept at it, volunteering for this potentially deadly trip like a cocky new kid trying to prove himself.

Johnson knew this wasn’t a game, back in 1901 he’d nearly been lynched himself in Jacksonville, Florida; but he’d brought White to New York for exactly this reason, to stir things up. He was a spark plug, not a sociologist. And even if no one had ever considered this kind of mission before, White was without question uniquely qualified for it. Not only was his skin light enough to open doors and, hopefully, mouths, but he’d survived the edgy summer of 1915, learned the ways of sleepy Southern towns. How different would this be, really, from those days? Most of all, though, it was what George and Madeline hadn’t taught their son that mattered most: Walter White was not intimidated by white America.

There’s no record of what White said to convince them, but three days later he was on a train to Chattanooga, armed with the Life Insurance Temperament and a set of credentials from the New York Evening Post given to him by the paper’s publisher, Oswald Garrison Villard, the grandson of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and an often contentious member of the NAACP board. If he were caught out somehow, maybe pretending he was a reporter would help him squirm out of trouble.

The trip was shorter than White claims in his autobiography, where he says he spent “days” in Estell Springs, a place “as remote from the outside world as though it had been in Tibet.” In fact, after a night in Chattanooga, eighty miles east of Estell Springs, he arrived in the town early on the 18th, and immediately checked into Goddard’s boardinghouse across the road from the railroad station. After feigning interest in some cotton land for sale by the landlord, White proceeded to the general store and presented himself as a traveling salesman from the Exelento Medicine Company. The townspeople were suspicious of this new arrival, but White reached back into his salesman’s training and, in a word, played them. Instead of asking questions, he acted not just ignorant of the lynching but completely indifferent to it, changing the subject until finally the white folks couldn’t hold back their pride any longer and laid out all the ghastly details White had come for without him having to even leave his seat at the potbellied stove. McIlherron, it turned out, had owned a large plot of land envied by whites and blacks alike. He was also famously truculent. The teenage boys, well-known troublemakers, had thrown rocks at him. McIlherron had reacted violently and then tried to escape from the town, accompanied by a local minister. The farmer was caught, tortured, and burned, the minister executed.

As he was busy with this “sleuthing,” as White calls it, he had the composure to write a remarkable letter to Shillady from the Goddard House, explaining the whole plan in buoyant terms that make it seem as if he’s down there playing a practical joke. It’s heroic in its way, the product of someone who’s already preparing to dine out on his adventure, and finishes with a request that Shillady tell Johnson that they hadn’t “lynched his Corona yet.” Still, White knew when to get out; the next morning, already back in Chattanooga, he sent a telegram to the office asking whether he should go on to Fayetteville, Georgia, where another lynching had just taken place. A few days later he was back in New York, safe and sound. He never looked back at Atlanta.

Within two weeks of finding his desk, White had proven himself invaluable to the NAACP. Through 1927 he would eventually investigate forty-one lynchings, eight race riots, and two cases of widespread peonage, risking his life repeatedly in the dank backwaters of Florida, the piney woods of Georgia, and the cotton fields of Arkansas in search of the truth. He didn’t so much enter the scene that February 1918 as he exploded, initiating nine years of nonstop work that placed him near the center of every sphere of black political, social, and artistic life in the 1920s. This experience in turn formed his power base in the following decades. What he accomplished for the NAACP in the teens and twenties investigation, congressional testimony, lobbying, fund-raising, speeches, writings, and close management of two landmark legal cases along with his literary accomplishments and social connections made White in many ways the epitome of the New Negro emergent in post World War I America, a man no longer willing passively to accept white oppression or simply beg for help.

But the sum of what White achieved in the nine years after Estell Springs doesn’t fully explain the role he came to play in the imagination of much of black America that decade. It wasn’t just his willingness to cheat death for the cause. It was how he did it that made him special. Every chance he had, Walter White got in the face of ignorant white America. He was a provocateur, dodging in and out of the clutches of danger, tweaking The Man’s nose as he did it, a trickster as annoying and funny and confounding as any you’d find in a folktale. And as soon as White stood up in a church basement or on the stage of an auditorium to tell his stories, that’s what he became, a character in a folktale.

Except, his tales were true.