Good Morning POU! Let’s talk about the Louisville Cardinals and the infamous Dr. Dunkenstein and the Doctors of Dunk!

Banned from college basketball in 1967, the dunk was ostensibly outlawed because of damaged equipment, injuries and aesthetics. But because the decision came down shortly after Lew Alcindor led UCLA to the NCAA championship at Freedom Hall, it became informally known as the “Alcindor rule.”

“Nobody would admit that that was the case,” said Denny Crum, then a UCLA assistant and later Louisville’s Hall of Fame coach. “But it had to be the overflowing factor. There was no one impacting the game like he did at that particular time in his career. For them to say that he didn’t influence that, believe me he had a huge influence on that.”

Enter Darrell Griffith.

Griffith was enormously influential in popularizing the dunk after the NCAA ban was lifted preceding his 1976-77 freshman year. “When we came to town,” Griffith said, “it was a road show.”

Reflecting on the cultural impact of his Louisville teams, Griffith said the college game had previously been “a little boring.”

“The dunk really brought the excitement back into the game,” he said. “It changed the trajectory. We were a team that pioneered all that.”

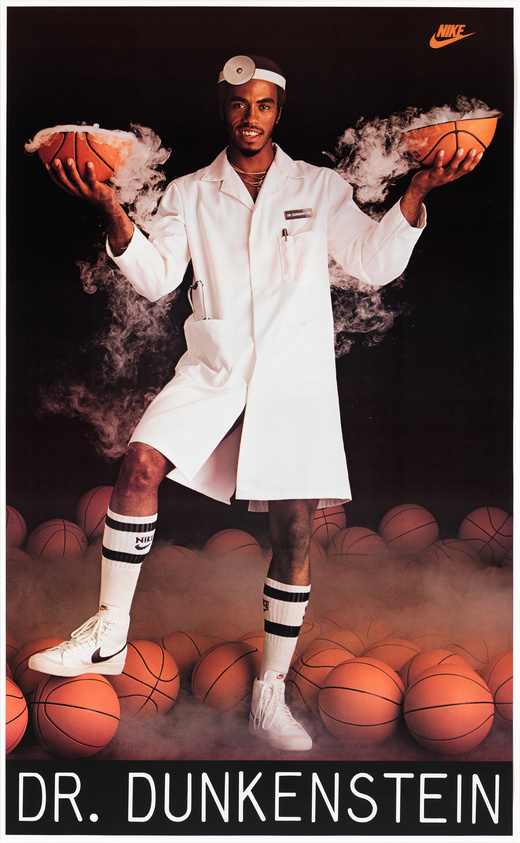

With their white lab coats and their high-altitude exploits, the Doctors of Dunk became a distinct basketball brand before Houston’s Phi Slamma Jamma or Michigan’s Fab Five. Dunks would become so synonymous with Louisville basketball that the school have been keeping track of them as a quasi-official statistic since before the NBA added a dunk contest to its NBA All-Star showcase in 1984.

Griffith’s 156 career dunks have since been surpassed by Montrezl Harrell (221) and Pervis Ellison (162) at U of L, but no Cardinal is so closely associated with basketball’s highest-percentage shot. When Griffith was inducted in the National College Basketball Hall of Fame in 2014, former LSU coach Dale Brown recalled his memorable fast-break windmill dunk in the 1980 Midwest Regional championship game.

“When he got that dunk, it was like someone threw a javelin in my heart,” Brown said. “We recruited Darrell Griffith, and when I first saw him, I thought I’d never have to ever meet an astronaut or a cosmonaut. He was further out in space than they were.”

Blessed with a vertical leap calculated as high as 48 inches, Griffith began dunking as a 7th grader. Prevented from demonstrating the full extent of his airborne abilities at Male High School by rules similar to the NCAA’s, Griffith recalled unauthorized dunking in layup lines until a trainer would wave a towel to alert players to the approach of the officials.

Freed from such constraints once he arrived at Louisville, Griffith and his teammates changed how college basketball was played and, to a large extent, how it was consumed.

“I don’t know if Coach Crum really knew the impact of our team till years later,” Griffith said Tuesday. “I knew we won the national championship (in 1980), but the impact culturally that we had on the landscape of college basketball — us being the team that brought the excitement back to college basketball. . .I’m pretty proud of that.”