There are three statues in the United States honoring Dr. James Marion Sims, a 19th-century physician dubbed the father of modern gynecology. Invisible in his shadow are the enslaved women whom he experimented on. Today, they are unknown and unnamed except for three: Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey.

On the shady northwest corner of the statehouse grounds in Columbia, South Carolina, a place wrought with controversy over its harsh, shameful tributes to slavery, sits a monument dedicated to James Marion Sims.

The monument honoring the South Carolinian from Lancaster County curiously dubbed “The Father of Gynecology” is one of the largest on the site. Directly beneath his image is a quote from Hippocrates, “Where the love of man is, there is also the love of art.” Etched in a panel to the left, an inscription touts, “The first surgeon of the ages in ministry to women, treating alike empress and slave.” On the panel to the right, the inscription continues, “He founded the science of gynecology, was honored in all lands and died with the benediction of mankind.”

Historians from South Carolina proudly proclaim that Dr. Sims innovated techniques and developed instruments that changed the landscape of women’s reproductive health. Outside accounts portray him quite differently. What is not in dispute is that between 1845 and 1849, on his property in Montgomery, AL, in a makeshift hospital he built in his backyard, Sims inaugurated a long, drawn-out series of excruciating, experimental gynecological operations on countless enslaved African women. This was all done without the benefit of anesthesia or before any type of antiseptic was used. Many lost their lives to infection. It is their story that history has failed to tell and their legacy of courage and endurance that should be honored, not their captor’s.

Enslaved African midwives were numerous throughout the South. For hundreds of years, childbirth was not considered a “sickness” and for the most part, physicians did not attend births. But in the mid-nineteenth century, the attitude of the white male medical practitioners towards midwifery was changing. Male-dominated medicine was now challenging female-governed childbirth. The African midwife’s spiritual traditions and knowledge of rituals and herbs handed down orally through generations earned her honor and respect among the enslaved. Just as the Southern physician was at the core of his social web, the midwife enjoyed the equivalent status. This could have fueled the white master’s need to remove them from positions of prominence. The early obstetricians chose to exclude midwives from their research and utterly dismissed their collective knowledge. Reminiscent of witch-hunts, persecution of midwives by white males was beginning to play out again on southern plantations.

By all accounts, Sims, like a vast majority of his antebellum Southern white counterparts, was a strong proponent of slavery. It was while administering medical care to a woman that came to him with a injured pelvis and retroverted uterus from a fall off of a horse, that he began his career in gynecology. In treating this patient, he developed a theory on how to treat the injury, but he needed more studies. Thus, when Sims wanted patients, he simply bought or rented the slaves from their owners.

Sims operated on at least 10 slave women from 1846 to 1849, perfecting his technique. It took dozens of operations before he finally reported success, having used special silver sutures to close the fistulas. Three of the slaves — Lucy, Anarcha and Betsy — all underwent multiple procedures without anesthesia, which had recently become available. Sims’s records show that he operated on Anarcha 30 times.

A common belief at the time was that black people did not feel as much pain as white people, and thus did not require anesthesia when undergoing surgery. Nevertheless, in a memoir he stated that “Lucy’s agony was extreme, she was much prostrated and I thought she was going to die”. After he operated on her in the presence of twelve doctors without anesthetics, she nearly died from septicemia following his experimental use of a sponge to wipe urine from the bladder during the procedure

Sims’s persistence aroused some alarm, and several physicians urged him to stop experimenting. In response, he later reported that the slave women had been ”clamorous” for the operation and had even assisted him with surgery.

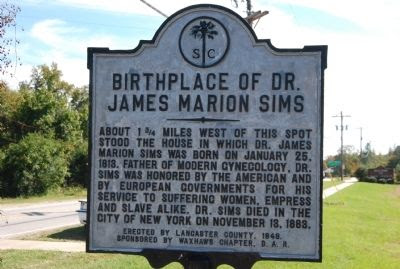

Sims’s contemporaries and early biographers heralded his feat. His skillful experiments, according to his obituary in The New York Times in 1883, ”were of great advantage to members of his profession in the treatment of female diseases.” An inscription near Sims’s birthplace termed him ”a blessing and a benefactor to women.”

Statues of Sims were erected in South Carolina, Alabama and New York City, where in 1855 he opened the first hospital exclusively for women. The New York statue stands in Central Park at Fifth Avenue and 103rd Street.

One of Sims’s modern legacies is the almost total absence of vesico-vaginal fistulas in the developed world, because of advances in childbirth and the operation he pioneered.

From this lofty perch, Sims had a long way to fall. And fall he did, beginning in the mid-1970’s, as Americans dealt with the volatile issues of racial and sexual equality. Historians, many of them sympathetic to the civil rights and women’s movements, saw an urgent need to revise Sims’s history.

One of the first scholars to weigh in was Dr. Graham J. Barker-Benfield, then a historian at Trinity College in England, who argued that Sims had used slave women as guinea pigs to advance his career.

During his early medical years, Sims also became interested in “trismus nascentium“, also known as Neonatal tetanus. It is a form of generalized tetanus that occurs in newborns. It usually occurs through infection of the unhealed umbilical stump, particularly when the stump is cut with a non-sterile instrument. Neonatal tetanus mostly occurs in developing countries, particularly those with the least developed health infrastructure. It is rare in developed countries.

“Trismus nascentium” is now recognized to be the result of unsanitary practices and nutritional deficiencies. At the time its cause was unknown, and it was an affliction of many African slave children. It is now believed that the conditions of the slave quarters were the cause. While Sims somewhat alluded to the idea that sanitation and living conditions played a role in contraction, he believed that the disease could be attributed to the idea that enslaved Africans were intellectually and morally superior. He described in his writing:

“Whenever there are poverty, and filth, and laziness, or where the intellectual capacity is cramped, the moral and social feelings blunted, there it will be oftener found. Wealth, a cultivated intellect, a refined mind, an affectionate heart, are comparatively exempt from the ravages of this unmercifully fatal malady. But expose this class to the same physical causes, and they become equal sufferers with the first.”

In addition to these racial beliefs, Sims thought trismus nascentium arose from skull bone movement during protracted births. To test this, Sims used a shoemaker’s awl to pry the skull bones of enslaved women’s babies into alignment; these experiments had a 100% fatality rate, and Sims often kept the corpses for autopsies and further research on the condition. He then blamed these fatalities on “the sloth and ignorance of their mothers and the black midwives who attended them,” as oppose to the extensive experimental surgeries that he conducted upon them.

The success of J. Marion Sims as “the father of gynecology” in the United States rested solely on the personal sacrifices of the enslaved African women he experimented on from 1845 to 1849. Had they not been his property,

giving him carte blanche to cut them open and sew them back up as he saw fit, he could have never devised the surgical technique that brought him international recognition. He never expressed any interest in the cause of

vesico-vaginal fistulas or in the health of the women themselves. Nor did he concern himself with the extent of recovery made by the patients. And never did he express moral uncertainty because he had kept several women

captive for the expressed purpose of painful surgical experimentation.

Undeniably, nineteenth century medical practices were crude and painful, but Sims’ contemporaries felt he was unnecessarily cruel. Other physicians of that

unfortunate era experimented on the enslaved, but among them, James Marion Sims was one of the worst.

Sources: Dr. J Marion Sims Dossier

Scholars Argue Over Legacy of Surgeon Who Was Lionized, Then Vilified

Dr. J. Marion Sims Medical Experiments on Enslaved Women and Children

Remembering Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey: The Mothers of Modern Gynecology