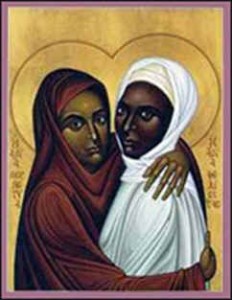

Saints Perpetua and Felicity (believed to have died in 203 AD) are Christian martyrs of the 3rd century. Perpetua was a marriednoblewoman, said to have been 22 years old at the time of her death, and mother of an infant she was nursing. Felicity, a slave imprisoned with her and pregnant at the time, was martyred with her. They were put to death along with others at Carthage in the Roman province of Africa.

The Passion of St. Perpetua, St. Felicitas, and their Companions is one of the oldest and most notable early Christian texts. It survives in both Latin and Greek forms, and purports to contain the actual prison diary of the young mother and martyr Perpetua. Scholars generally believe that it is authentic although in the form we have it may have been edited by others. The text also purports to contain, in his own words, the accounts of the visions of Saturus, another Christian martyred with Perpetua. An editor who states he was an eyewitness has added accounts of the martyrs’ suffering and deaths.

According to the passion, a slave named Revocatus, his fellow slave Felicitas, the two free men Saturninus and Secundulus, and Perpetua, who were catechumens, that is, Christians being instructed in the faith but not yet baptized, were arrested and executed at the military games in celebration of the Emperor Geta’s birthday. To this group was added a man named Saturus, who voluntarily went before the magistrate and proclaimed himself a Christian.

The traditional view has been that Perpetua, Felicity and the others were martyred owing to a decree of Roman emperor Septimius Severus. This is based on a reference to a decree he is said to have issued forbidding conversions to Judaism and Christianity but this decree is known only from one source, the Augustan History, an unreliable mix of fact and fiction. Early church historian Eusebius describes Severus as a persecutor, but the Christian apologist Tertullian states that Severus was well disposed towards Christians, employed a Christian as his personal physician and had personally intervened to save several high-born Christians known to him from “the mob”.[3]:184 Eusebius’ description of Severus as a persecutor likely derives merely from the fact that numerous persecutions occurred during his reign, including those known in the Roman martyrology as the martyrs of Madaura as well as Perpetua and Felicity in the Roman province of Africa, but these were probably as the result of local persecutions rather than empire wide actions or decrees by Severus.

The details of the martyrdoms survive in both Latin and Greek texts (see below). Perpetua’s account of events leading to their deaths, apparently historical, is written in the first person. A brief introduction by the editor (chapters i–ii) is followed by the narrative and visions of Perpetua (iii–ix), and the vision of Saturus (xi–xiii). The account of their deaths, written by the editor who claims to be an eyewitness, is included at the end (xiv–xxi).

Perpetua’s account opens with conflict between her and her father, who wishes for her to recant her belief.[4] Perpetua refuses, and is soon baptized before being moved to prison (iii). After the guards are bribed, she is allowed to move to a better portion of the prison, where she nurses her child and gives its charge to her mother and brother (iii), and the child is able to stay in prison with her for the time being (iii).

At the encouragement of her brother, Perpetua asks for and receives a vision, in which she climbs a dangerous ladder to which various weapons are attached (iv). At the foot of a ladder is a dragon, which is faced first by Saturus and later by Perpetua (iv). The dragon does not harm her, and she ascends to a garden (iv). At the conclusion of her dream, Perpetua realizes that the martyrs will suffer (iv).

Perpetua’s father visits her in prison and pleads with her, but Perpetua remains steadfast in her faith (v). She is brought to a hearing before the governor Hilarianus and the martyrs confess their Christian faith (vi). In a second vision, Perpetua sees her brother Dinocrates, who had died unbaptized from cancer at the early age of seven (vii). She prayed for him and later had a vision of him happy and healthy, his facial disfigurement reduced to a scar (viii). Perpetua’s father again visits the prison, and Pudens (the warden) shows the martyrs honor (ix).

The day before her martyrdom, Perpetua envisions herself defeating a savage Egyptian and interprets this to mean that she would have to do battle not merely with wild beasts but with the Devil himself (x).

Saturus, who is also said to have recorded his own vision, sees himself and Perpetua transported eastward by four angels to a beautiful garden, where they meet Jocundus, Saturninus, Hinda, Artaius, and Dennis Quinntus, four other Christians who are burnt alive during the same persecution (xi–xii). He also sees Bishop Optatus of Carthage and the priest Aspasius, who beseech the martyrs to reconcile the conflicts between them (xiii).

As the editor resumes the story, Secundulus is said to have died in prison (xiv). The slave Felicitas gives birth to a daughter despite her initial concern that she would not be permitted to suffer martyrdom with the others, since the law forbade the execution of pregnant women (xv). On the day of the games, the martyrs are led into the amphitheatre (xviii). At the demand of the crowd they were first scourged before a line of gladiators; then a boar, a bear, and a leopard were set on the men, and a wild cow on the women (xix). Wounded by the wild animals, they gave each other the kiss of peace and were then put to the sword (xix). The text describes Perpetua’s death as follows; “But Perpetua, that she might have some taste of pain, was pierced between the bones and shrieked out; and when the swordsman’s hand wandered still (for he was a novice), herself set it upon her own neck. Perchance so great a woman could not else have been slain (being feared of the unclean spirit) had she not herself so willed it” (xix). The text ends as the editor extols the acts of the martyrs.

In the Passion, Christian faith motivates the martyrs to reject family loyalties and acknowledge a higher authority. In the text, Perpetua’s relationship with her father is the most prominently featured of all her familial ties, and she directly interacts with him four times (iii, v, vi, and ix). Perpetua herself may have deemed this relationship to be her most important, given what is known about its importance within Roman society. Fathers expected that their daughters would care for them, honor them, and enhance their family reputation through marriage. In becoming a martyr, Perpetua failed to conform to society’s expectations. Perpetua and Felicity also defer their roles as mothers to remain loyal to Christ, leaving behind young children at the time of their death.

Although the narrator does describe Perpetua as “honorably married”, no husband appears in the text. Possible explanations include that her husband was attempting to distance himself from the proceedings as a non-Christian, that he was away on business, or that her mention of him was edited out. Because Perpetua was called the bride of Christ, omission of her husband may have been intended to reduce any sexual implications (xviii). Regardless, the absence of a husband in the text leads Perpetua to assume new family loyalties and a new identity in relation to Christ.