Good morning POU Family! It’s Tuesday. Continuing on with this week’s theme, we will continue to highlight events and people around the era entitled, “The Nadir of American Race Relations.”

Reconstruction Era Violence

For several years after the war, the federal government, pushed by Northern opinion, showed itself willing to intervene to protect the rights of black Americans. There were limits, however, to Republican efforts on behalf of blacks: in Washington, a proposal of land reform made by the Freedmen’s Bureau which would have granted blacks plots on the plantation land (forty acres and a mule) they worked never came to pass.

In the South, they stripped many former Confederates of the right to vote, but they resisted Reconstruction with violence and intimidation. James Loewen notes that between 1865 and 1867, when white Democrats controlled the government, whites murdered an average of one black person every day in Hinds County, Mississippi. Black schools were especially targeted: school buildings were frequently burned and teachers were flogged and occasionally murdered. The postwar terrorist group the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) acted with significant local support, attacking freedmen and their white allies; federal efforts under the Enforcement suppressed the group Acts of 1870–71, but did not disappear and had a resurgence in the early twentieth century.

Despite these failures, however, blacks continued to vote and attend schools. Literacy soared, and many African-Americans were elected to local and statewide offices, with several serving in Congress. Because of the black community’s commitment to education, most blacks were literate by 1900.

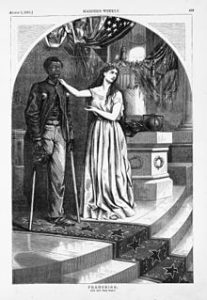

“Colored Rule in a Reconstructed(?) State”, Harper’s Weekly, March 14, 1874. Nine years later, Nast had given up on racial idealism. He caricatured black legislators as incompetent buffoons.

“Colored Rule in a Reconstructed(?) State”, Harper’s Weekly, March 14, 1874. Nine years later, Nast had given up on racial idealism. He caricatured black legislators as incompetent buffoons.

Continued violence in the South, especially heated around electoral campaigns, sapped Northern intentions. More significantly, after the long years and losses of the Civil War, Northerners had lost heart for the massive commitment of money and arms that would have been required to stifle the white insurgency. The financial panic of 1873 disrupted the economy nationwide, causing more difficulties. The white insurgency took on new life ten years after the war. Conservative white Democrats waged an increasingly violent campaign, with the Colfax and Coushatta Massacres in Louisiana in 1873 as signs.

The next year saw the formation of paramilitary groups, such as the White League in Louisiana (1874) and Red Shirts in Mississippi and the Carolinas, that worked openly to turn Republicans out of office, disrupt black organizing, and intimidate and suppress black voting. They invited press coverage. One historian described them as “the military arm of the Democratic Party.”

In 1874, in a continuation of the disputed gubernatorial election of 1872, thousands of White League  militiamen fought against New Orleans police and Louisiana state militia and won. They turned out the Republican governor and installed the Democrat Samuel D. McEnery, took over the capitol, state house and armory for a few days, and then retreated in the face of Federal troops. This was known as the “Battle of Liberty Place”.

militiamen fought against New Orleans police and Louisiana state militia and won. They turned out the Republican governor and installed the Democrat Samuel D. McEnery, took over the capitol, state house and armory for a few days, and then retreated in the face of Federal troops. This was known as the “Battle of Liberty Place”.

End of Reconstruction

Main article: Disenfranchisement after the Reconstruction Era

Northerners waffled and finally capitulated to the South, giving up on being able to control election violence. Abolitionist leaders like Horace Greeley allied themselves with Democrats in attacking Reconstruction governments. By 1875, there was a Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. President Ulysses S. Grant, who as a general had led the Union to victory in the Civil War, initially refused to send troops to Mississippi in 1875 when the governor of the state asked him to.

Violence surrounded the presidential election of 1876 in many areas, beginning a trend. After Grant, it would be many years before any President would do anything to extend the protection of the law to black people.