(from Our Kind Of People, Chapter 1)

The Evil Sun

All my life, for as long as I can remember, I grew up thinking that there existed only two types of black people: those who passed the “brown paper bag and ruler test” and those who didn’t. Those who were members of the black elite. And those who weren’t.

I recall summertime visits from my maternal great-grandmother, a well-educated, light-complexioned, straight-haired black southern woman who discouraged me and my brother from associating with darker-skinned children or from standing or playing for long periods in the July sunlight, which threatened to blacken our already too-dark skin. “You boys stay out of that terrible sun,” Great-grandmother Porter would say in a kindly, overprotective tone. “God knows you’re dark enough already.”

As she sat rocking, stiff-lipped and humorless, on the porch of our Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard, summer home, she would gesture for us to move further and further into the shade while flipping disgustedly through the pages of Ebony magazine. “Niggers, niggers, niggers,” she’d say under her breath while staring at the oversized pages of text and photos of popular Negro politicians, entertainers, and sports figures who were busy making black news in 1968. Great-grandmother Porter, the daughter of a minister and a homemaker, was extremely proud of her Memphis, Tennessee, middle-class roots. While still a child, she had worn silk taffeta dresses, had taken several years of piano lessons, and had managed to become fluent in French.

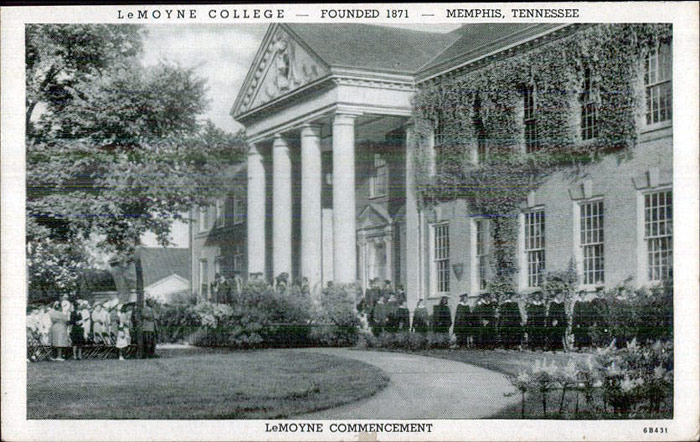

Her only daughter had followed in her footsteps, wearing similarly elegant dresses, taking music lessons, and attending the private LeMoyne School a few years ahead of Roberta Church, the millionaire daughter of Robert Church, the richest black man in the South. She often reminded us that one of her sisters, Venie, then grown and married, had lived for years on Mississippi Boulevard next door to Maceo Walker, the most affluent and powerful black man in Memphis. Great-grandmother was proud of many things, such as being a Republican like the Churches and most other well-placed blacks in those early years.

Like all blacks in racist southern towns in the early 1900s, she despised the insults, the substandard treatment, and the poor facilities that the Jim Crow laws had left for blacks. But like many blacks of her class, she was able to limit the interactions that she and her family had with such indignities. Rather than ride at the back of the bus and send her daughter to substandard segregated public schools, she and her husband bought a car and paid for private schooling. For my great-grandmother, life had been generous enough that she could create an environment that buffered her family against the bigotry she knew was just outside her door.

Even though it was 1968, a period of unrest for many blacks throughout the country, Great-grandmother—like the blue-veined crowd that she was proud to belong to—seemed, at times, to be totally divorced from the black anxiety and misery that we saw on the TV news and in the papers. In public and around us children, her remarks often suggested that she was satisfied with the way things were. She often said she didn’t think much of the civil rights movement (“I don’t see anything civil about a bunch of nappy-headed Negroes screaming and marching around in the streets”), even though I later learned that she and her church friends often gave money to the NAACP, the Urban League, and other groups that fought segregation.

She said she didn’t think much of Marvin Gaye or Aretha Franklin or their loud Baptist music (“When are we going to get beyond all this low-class, Baptist, spiritual-sounding rock and roll music?”), even though she would sometimes attend Baptist services. She was proud when a black man finally won an Academy Award, but was disappointed that Sidney Poitier seemed so dark and wet with perspiration when he was interviewed after receiving the honor. An outsider might have looked at this woman and wondered whether she liked blacks at all. Her views seemed so unforgiving. The fact was that she was completely dedicated to the members of her race, but she had a greater understanding of and appreciation for those blacks who shared her appearance and socioeconomic background.

“Young men—young men,” her voice called from the rear bedroom, “you aren’t back in that sun, are you?” “No, ma’am. We’re in the shade, ma’am,” my eight-year-old brother, Richard, called back with complete conviction as he stopped just out of my great-grandmother’s range of vision, thrusting his bare brown chest and oval face into the ninety-six-degree July sun, boldly willing his skin to grow blacker and blacker in defiance of her query.

Even at age six, I knew the importance of class distinctions within my black world. As I moved quickly to the safety of the shade, beckoning my brother to protect his complexion from the blackening sun, I gave legitimacy to my great-grandmother’s—and many of my people’s— fears. At age six, I already understood the importance of achieving a better shade of black. Unlike my brother, I already knew that there was us and there was them. There were those children who belonged to Jack and Jill and summered in Sag Harbor; Highland Beach; or Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard; and there were those who didn’t. There were those mothers who graduated from Spelman or Fisk and joined AKA, the Deltas, the Links, and the Girl Friends, and there were those who didn’t. There were those fathers who were dentists, lawyers, and physicians from Howard or Meharry and who were Alphas, Kappas, or Omegas and members of the Comus, the Boulé, or the Guardsmen, and there were those who weren’t.

There were those who could look back two or three generations and point to relatives who owned insurance companies, newspapers, funeral homes, local banks, trucking companies, restaurants, catering firms, or farmland, and there were those who couldn’t. There were those families that made what some called “a handsome picture” of people with “good hair” (wavy or straight), with “nice complexions” (light brown to nearly white), with “sharp features” (thin nose, thin lips, sharp jaw) and curiously non-Negroid hazel, green, or blue eyes—and there were those that didn’t.

I had a precious few of the above, while many I knew and played with were able to check off all the right boxes. In fact, I knew some who not only had complexions ten shades lighter than that brown paper bag, and hair as straight as any ruler, but also had multiple generations of “good looks,” wealth, and accomplishment. And, of course, I also knew some black kids who could claim nothing at all. It was a color thing and a class thing. And for generations of black people, color and class have been inexorably tied together. Since I was born and raised around people with a focus on many of these characteristics, it should be no surprise that I was later to decide—at age twenty-six—to have my nose surgically altered just so that I could further buy into the aesthetic biases that many among the black elite hold so dear. During my youth, it was often painful for me to acknowledge that I had one foot inside and one foot outside of this group. I never quite had enough of the elite credentials to impress the key leaders in the group, but my family and I checked off enough boxes to be embraced by a segment of this community. Sometimes I knew where I was lacking and sometimes I didn’t.

For example, I knew that my complexion was a shade lighter than the brown paper bag, but that my hair—while not coarse like our African ancestors’—had a Negroid kink that made it the antithe sis of ruler-straight. I knew that we lived in the right neighborhood, summered at the right resorts, and employed the right level of household help, but that we had not attended the right private schools or summer camps. While my grandparents owned businesses and property that brought them and their children an unusually high standard of living, none of them had gone to the right schools.

My mother was accepted by the old guard’s most exclusive women’s social club, but my father belonged to a fraternity that the elite group considered to be “distinctly middle-class.” My brother and I grew up in the country’s most exclusive black children’s group, yet we were never invited to serve as escorts in the best debutante cotillions. But whether it was mainly the skin color, the hair texture, the family background, the education, the money, or the sharpness of our features that set some of us apart and made some of us think we were superior to other blacks—and to most whites—we were certain that we would always be able to recognize our kind of people.