Good Morning POU! We continue reading the Equal Justice Initiative’s report on the period of Reconstruction.

On the question of racial equality, there was often little distinction between slavery’s white supporters and detractors. “God has made the negro an inferior being not in most cases, but in all cases,” leading pro-slavery New Yorker John H. Van Evrie wrote in the 1850s. Even New England abolitionist Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe openly expressed the view that Black people were naturally inferior to white people. He tried to drum up support for abolition by assuring white people that Black people would “dwindle and gradually disappear from the peoples of this continent” if freed. Clearly an end to enslavement alone would not emancipate Black people from racism. But first things would have to come first.

Beginning in 1861, Southern states determined to maintain enslavement seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America.

In South Carolina, the first state to secede, legislators declared that “[a]n increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery” was a primary catalyst for their action. As Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee followed, the Confederacy developed a platform of “states’ rights” and “home rule” that aimed to preserve white supremacy and enslavement.

Even before the war’s end, Confederate hatred for Black autonomy and power led to brutal attacks. Black soldiers in the Union Army symbolized the height of Black “disobedience” and became immediate targets for violence that exceeded even the bounds of war.

When an outnumbered “colored” unit of the Union Army surrendered Fort Pillow, Tennessee, to Confederate forces on April 12, 1864, the rules of war required the Confederates to take the 262 Black soldiers as prisoners. Instead, the Confederates massacred the Black men, along with nearby Black civilians. A later federal investigation concluded: “It is the intention of the rebel authorities not to recognize the officers and men of our colored regiments as entitled to the treatment accorded by all civilized nations to prisoners of war.”

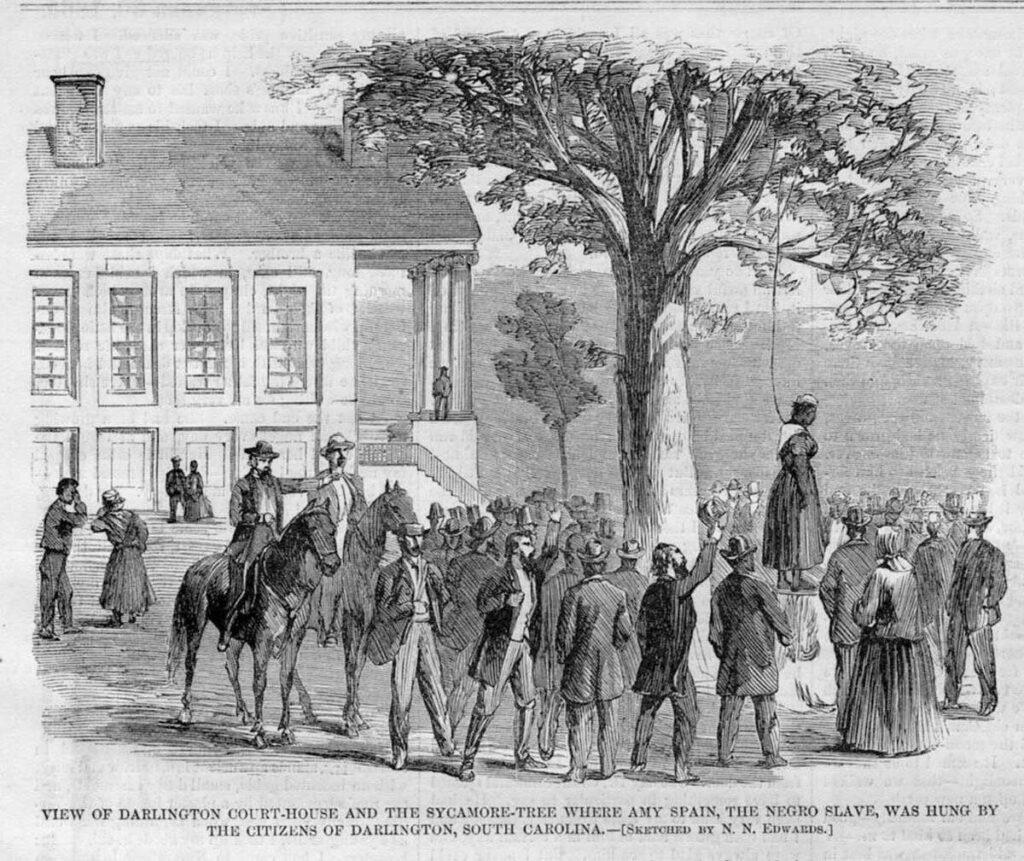

On March 10, 1865, Confederate soldiers in Darlington, South Carolina, hanged a young Black woman named Amy Spain from a sycamore tree on the courthouse lawn. Accused of “treason and conduct unbecoming a slave” for aiding Union forces who had briefly occupied the town, Ms. Spain was killed just weeks before the end of the Civil War.

By the time the war ended with Confederate surrender to the Union on April 9, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln had issued an Emancipation Proclamation abolishing slavery in the rebel territories and Congress had advanced a constitutional amendment that aimed to abolish slavery nationwide. “Slavery is dead,” read an editorial in The Cincinnati Enquirer published days after the surrender. “The negro is not; there is our misfortune.”17

If the end of the war led the United States government to abandon the millions of Black people still living in the war-torn South amidst a beaten Confederacy, those emancipated people’s futures in freedom would be bleak and short-lived. In a November 1865 letter to Major General Steadman of the Union Army, 125 freedmen in Columbus, Georgia, begged federal troops to stay in the city:

We wish to inform you that if the Federal Soldiers are withdrawn from us, we will be left in a most gloomy and helpless condition. A number of Freedmen have already been killed in this section of country; and . . . we have every reason to fear that others will share a similar fate.

Formerly enslaved Black people understood that federal intervention was necessary to require white Southerners to honor their rights as Americans. Their letter ended by pleading for federal troops “not to leave us to the tender mercy of our enemies—unprotected.”19

Decades later, in his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois described the reality Black people faced. “Not a single Southern legislature stood ready to admit a Negro, under any conditions, to the polls,” he explained.

Not a single Southern legislature believed free Negro labor was possible without a system of restrictions that took all its freedom away; there was scarcely a white man in the South who did not honestly regard Emancipation as a crime, and its practical nullification as a duty.

After the Confederacy’s defeat, the United States was preserved but devastated, and faced an uncertain future. Many of the day’s most pressing questions asked: what would happen to the entrenched institution of slavery? And what fate would befall the millions of Black people who had been enslaved at the war’s start?

The 1863 Emancipation Proclamation left these questions unanswered. How the nation would travel from war to peace depended on how it would chart Black Americans’ path from slavery to freedom. Reconstruction became that path, but its initially hopeful promise proved to be short-lived, dangerous, and deadly.