“Grabbing Our Stuff and Ruining It”

The white people are pushing themselves among the colored. —Chandler Owen, “The Black and Tan Cabaret”

Depending who you talk to, Carl Van Vechten was either a trusted friend and confidant to 1920s Harlem or an interloping tourist who used his privilege to get close to the period’s leading black culturati. That the white music critic-writer-portrait photographer dedicated his energies to the cultural life of Harlem is undisputed—Van Vechten used his massive trust fund to live a life on the wild side, partying and photographing in Harlem by night, resting and writing in his Upper West Side apartment by day.

In modern terms, Van Vechten was a hipster.

As an appreciator of the arts, noted Negrotarian Carl Van Vechten was extremely intrigued by the explosion of creativity which was occurring in Harlem. He was drawn towards the tolerance of Harlem society and its draw towards black writers and artists. He also felt most accepted there as a gay man (though he was married for more than 50 years). Van Vechten promoted many of the major figures of the Harlem Renaissance, including Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, Ethel Waters, Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston and Wallace Thurman (members of Hurston’s self proclaimed Niggerati ensemble).

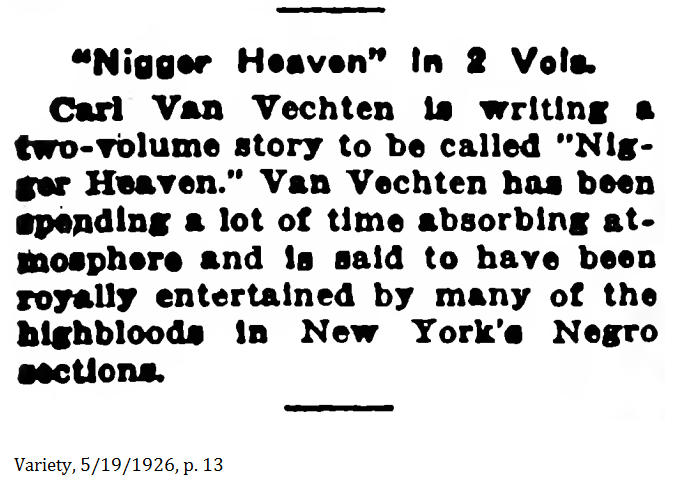

It was Van Vechten’s controversial novel Nigger Heaven, published in 1926, that for many black writers, crossed a line that once again exposed the “Negrotarian’s” arrogant familiarity. His essay “Negro Blues Singers” was also published in Vanity Fair in 1926. Biographer Edward White suggests Van Vechten was convinced that Negro culture was the essence of America, and his right to make it his own.

Van Vechten, as did many Negrotarian patrons, played a critical role in the Harlem Renaissance and helped to bring greater clarity to the African American movement. However for a long time he was also seen as a very controversial figure. In Van Vechten’s early writings he claimed that Black people were born to be entertainers and sexually “free”. In other words he believed that black people should be free to explore their sexuality and singers should follow their natural talents such as jazz, spirituals and blues (but not classical music).

In Harlem, Van Vechten often attended clubs and cabarets. He was credited for the surge in white interest in Harlem nightlife and culture. He was also involved in helping well respected writers like Langston Hughes and Nella Larsen find publishers for their first works (which meant they had to put up with his ass).

At a time when literature was the social currency of public debate, the arts were at the heart of the Harlem Renaissance. Believing that accurate representations of blacks would turn the tide of American racism, black artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance “promoted poetry, prose, painting and music as if their lives depended on it.” In the words of diplomat, writer, editor, and activist James Weldon Johnson, “the final measure of the greatness of all peoples is the amount and standard of the literature and art they have produced. . . . ‘Through his artistic efforts the Negro is smashing the race barriers faster than he has ever done through any other method.’”

Given those stakes, it should not be surprising that Harlem’s black writers watched with dismay as white writers including Van Vetchen became more successful for depicting black life than they were.

No book ignited as much of a firestorm in Harlem as Van Vechten’s 1926 novel, Nigger Heaven. Having lauded the “wealth of novel, erotic, picturesque material” available to the artist who tackles “the squalor of Negro life, the vice of Negro life,” Van Vechten evidently decided to exploit the material himself. Nigger Heaven is a fairly predictable story of a troubled romance between a black Harlem librarian and her would-be writer lover as they battle racism in New York against a violent and sometimes sensationalized backdrop of Harlem’s nightlife.

Most of the novel is sympathetic to middle-class blacks and a serious treatment of such important Harlem Renaissance themes as interracial marriage, passing, racial solidarity, patronage, the idea of Harlem as “a sort of Mecca,” the “one-drop rule,” race discrimination, primitivism, and black arts. But the opening pages in particular are peopled with enough sensational Harlem figures—“jigchasers,” “high yellows,” “Bolito” players, “ofays,” “dicties,” “pink-chasers,” “bulldikers,” “arnchies,” “creepers,” and “Miss Annies”—to necessitate a “Glossary of Negro Words and Phrases” for white readers. Van Vechten’s black people have “a primitive birthright . . . that all civilized races were struggling to get back to . . . this love of drums, of exciting rhythms, this naïve delight in glowing colour . . . this warm sexual emotion.”

Van Vechten discussed the title with poet Countee Cullen, who was enraged by it, and they had several arguments over it. According to reviewer Kelefa Sanneh, one interpretation is that because Van Vechten had cultivated many professional and personal relationships in Harlem, he felt he, a white man, had license to use the pejorative, but Van Vechten also suggested that he knew most would still be offended and not forgive him. Van Vechten was not averse to having the controversy serve as publicity, and he knew at least some in Harlem would defend him. The book was successfully marketed to whites to exploit their fascination with the other side of town. Cullen found the novel so offensive that he refused to talk to him for 14 years.

The book fueled a period of “Harlemania”, during which the neighborhood became en vogue among white people, who then frequented its cabarets, bars, and so on.