Good Morning POU!

We continue to look at the Exodusters Movement. Today, what led to former slaves moving to the southwest at such a great pace and why the southwest, particularly, Kansas?

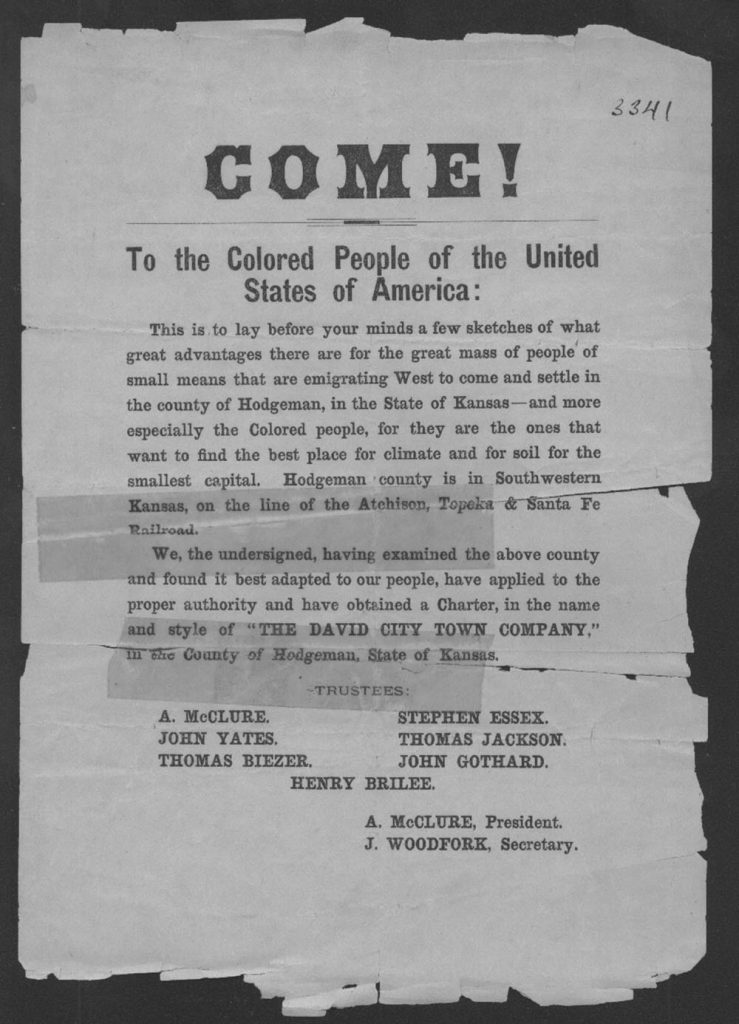

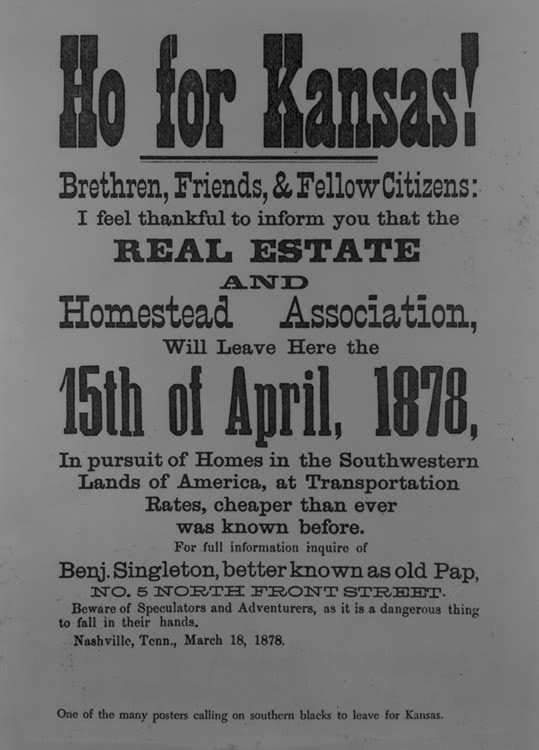

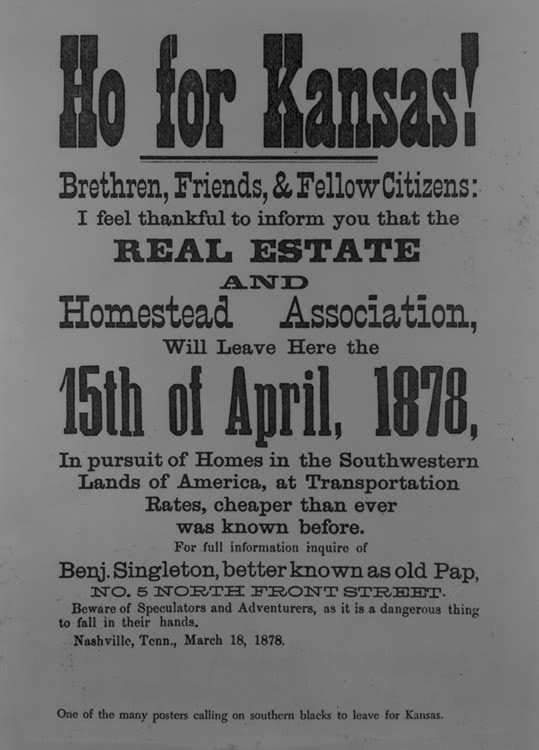

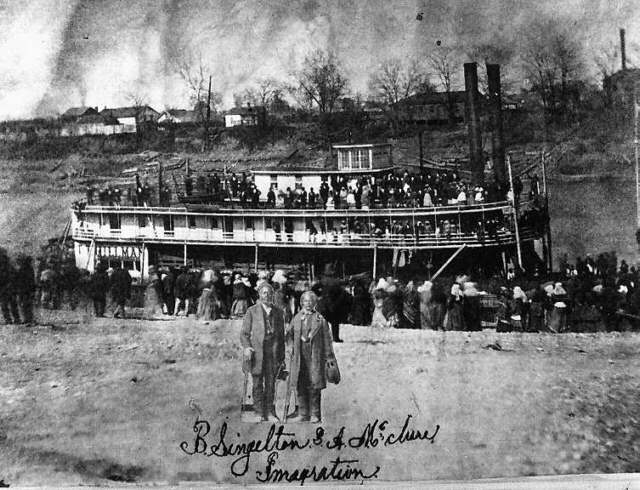

Benjamin Singleton, and S.A. McClure, Leaders of the Exodus, leaving Nashville, Tennessee with former slaves.

Conditions in the Post-War South

The post-Civil War era should have been a time of jubilation and progress for the African-Americans of the South. Slavery was nothing more than a bad memory; the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution had granted them citizenship; the Fifteenth Amendment outlawed suffrage discrimination based on race, color, or previous slave status. However, many Southern whites sought to keep blacks effectively disenfranchised and socially and economically inferior.

One way whites in power attempted to prevent black equality was through denial of African-American participation in the political process. Freed blacks were great supporters of the Republican Party, which was the party of Lincoln and emancipation. Much of the white South, however, remained loyal to the Democratic Party and professed hatred for all Republicans, black or white. When blacks turned out in droves to cast their ballots for Republican candidates, they were often met at the polls by whites employing creative means to keep the African-Americans from ever seeing the inside of the voting booth. Many African-Americans were prevented from casting their ballots and assuming their places as full members of the society. In addition to maintaining some semblance of the post-war balance of power, these methods also helped elect white Democrats.

Economic obstacles unique to their condition also prevented many freed blacks from moving ahead. After having been slaves for most of their lives, they knew only how to be farmers. Even for those that did possess or acquire alternative skills, the region’s lack of alternatives to farming as well as determined white supremacy blocked the freedmen’s advance. As farmers, they had no money to purchase land of their own, and many were actually forced to go back to work for the very same whites who had held them in bondage for so many years. The only difference was that the white landowners now paid them with a share of the crop which, after deductions for food and other necessities, amounted to a ridiculously low wage for their work. Though this did not technically constitute a master-slave relationship, it likely seemed hardly better than one to the African-Americans that had to endure such humiliation and frustration. Many of the freed blacks had few other skills, however, and often had families of their own to support. It must have seemed a no-win situation.

The era of Reconstruction in the South lasted from 1865 to 1877. During these years, federal troops occupied the states of the former Confederacy to ensure compliance with laws and regulations governing Southern states’ re-entry into the Union. Though the protection these troops provided to African-Americans was often minimal, it had been better than nothing. President Rutherford B. Hayes ended Reconstruction in 1877 and pulled the U.S. troops out of the South. This gave the white ruling class of the South free reign to terrorize and oppress freed blacks without interference from the U.S. Army or anyone else. Murders, lynchings and other violent crimes against blacks increased dramatically. It was likely at this point that many African-Americans began to feel that leaving the South forever was their only real chance to begin new lives. Movement to parts further west, such as Kansas, began almost immediately after the end of Reconstruction.

Black Migration to Kansas Prior to the Great Exodus

What was it about Kansas that particularly attracted African-Americans to that state? At the time that many blacks began to consider abandoning the South, there was certainly a good deal of frontier land available elsewhere. Besides slick (and often misleading) promotion of town sites, what drew freed men and women to Kansas?

First, purely logistical and geographic factors must be considered. Kansas, while certainly never considered a part of the South (except by pro-slavery Missourians prior to the Civil War), is much closer to the South than far-off spots like California and Oregon. Getting to Kansas was a much simpler and less expensive task than getting to such faraway places. For those coming from many parts of the South, a boat or train ride to St. Louis was the real beginning of their journey to Kansas. While conditions on these boats and trains were never ideal, riding in any form was certainly preferable to walking. Many arrived in St. Louis with little idea how they would get across Missouri and into Kansas. They must have felt, however, that whatever hardships they faced on that leg of the journey would be less significant than those left behind in the South.

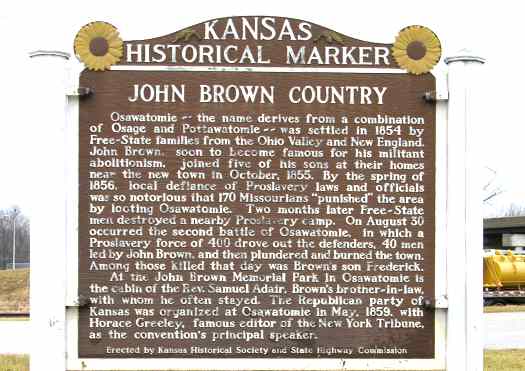

Another factor—a human one—also played a role in the selection of Kansas as the new Promised Land. The exploits of anti-slavery activists like John Brown gave Kansas an almost holy sacredness to many African-Americans. In Kansas, blood had been spilled to keep slavery out. The memories of John Brown and other abolitionist warriors lived on in the hearts and minds of freed men and women and made Kansas seem the ideal place to begin anew.

Many of the African-Americans that migrated to Kansas prior to the 1879 exodus came from Tennessee. There a popular movement sprang seemingly from nowhere in 1874, leading to a “colored people’s convention” in Nashville in May 1875. Many town promoters, including the notable Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, saw this convention as a way to convince people to migrate to Kansas. The convention resulted in the designation of a board of commissioners to officially promote migration to Kansas. This board would later stipulate that would-be migrants needed at least $1,000 per family to relocate to Kansas; very few interested in doing so had such funds. Nevertheless, many freed blacks determined to leave Tennessee anyway. Promoters like Singleton became known as “conductors” and began leading African-American families to Kansas.

Obviously, black migration to Kansas did not begin (or end) with the exodus of 1879. Thousands of freed blacks made their ways to Kansas throughout the decade of the 1870s. Since their migration was more gradual, however, few whites took notice. This was certainly not the case when the well-publicized exodus took place in 1879.

Tomorrow: the events of 1879