Good Morning POU!

The South Side Writers Group was a circle of African-American writers and poets formed in the 1930s in Chicago, which included Richard Wright, Arna Bontemps, Margaret Walker, Fenton Johnson, Theodore Ward, Garfield Gordon, Frank Marshall Davis, Julius Weil, Dorothy Sutton, Russell Marshall, Robert Davis, Marion Perkins, Arthur Bland, Fern Gayden, and Alberta Sims. Consisting of some twenty authors, the group championed Social Realism. Social Realism refers to the work of writers, artists and filmmakers who draw attention to the everyday conditions of the working classes and the poor, and who are critical of the social structures that maintain these conditions.

It was Wright, who in 1936, founded the South Side Writers Group in order to provide inspiration and encouragement to budding writers and space to experiment with new themes and subjects. The group met at the Abraham Lincoln Centre on South Cottage Grove Avenue near the Bronzeville District.

Gwendolyn Brooks

When Brooks was six weeks old, her family moved to Chicago during the Great Migration; from then on, Chicago remained her home. Brooks first attended a leading white high school in the city, Hyde Park High School, transferred to the all-black Wendell Phillips, and then to the integrated Englewood High School. After completing high school, she graduated in 1936 from Wilson Junior College, now known as Kennedy-King College. Williams noted, “These four schools gave her a perspective on racial dynamics in the city that continued to influence her work.

After these early educational experiences, Brooks never pursued a four-year degree because she knew she wanted to be a writer and considered it unnecessary. “I am not a scholar,” she later said. “I’m just a writer who loves to write and will always write.” She worked as a typist to support herself while she pursued her career.

She would closely identify with Chicago for the rest of her life. In a 1994 interview, she remarked on this,

“Living in the city, I wrote differently than I would have if I had been raised in Topeka, KS…I am an organic Chicagoan. Living there has given me a multiplicity of characters to aspire for. I hope to live there the rest of my days. That’s my headquarters.”

Brooks’ published her first book of poetry, the highly acclaimed A Street in Bronzeville (1945), with Harper and Row, after strong show of support to the publisher from author Richard Wright. He said to the editors who solicited his opinion on Brooks’ work,

“There is no self-pity here, not a striving for effects. She takes hold of reality as it is and renders it faithfully…She easily catches the pathos of petty destinies; the whimper of the wounded; the tiny accidents that plague the lives of the desperately poor, and the problem of color prejudice among Negroes.”

The book earned instant critical acclaim for its authentic and textured portraits of life in Bronzeville. Brooks later said it was a glowing review by Paul Engle in the Chicago Tribune that “initiated My Reputation.” Engle stated that Brooks’ poems were no more “Negro poetry” than Robert Frost’s work was “white poetry.”

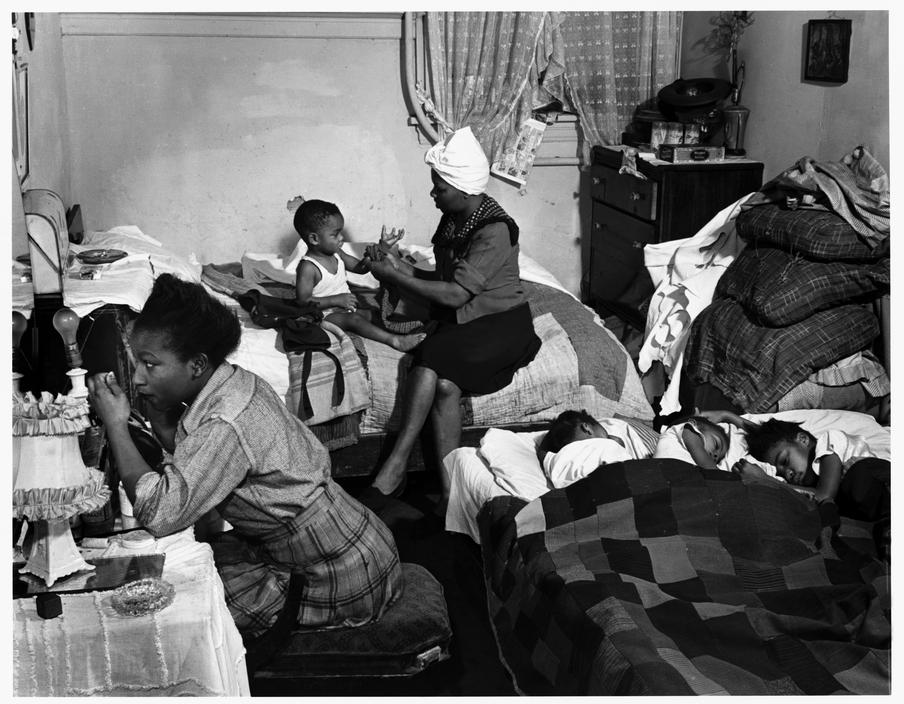

The end of World War II was the start of discriminatory housing practices and unofficial segregation aimed at African-American families in inner-city Chicago. These cramped kitchenette buildings were usually run by predatory landlords and kept in poor condition. The kitchenettes were often just one small room, and bathrooms and kitchens were shared with several other families. (Sharing a bathroom with your own siblings seems bad enough; now imagine having to share with other people’s siblings.)

Like many of Brooks’s poems, “Kitchenette Building”explores the lives of African-Americans living in a time of extreme discrimination without ever coming out and saying that. She approaches the subject of discrimination not from a political standpoint, but from the speaker’s personal experience. It’s because of this point of view that Brooks’s poems never read like a history lesson, but an intimate glimpse into someone’s life.

We are things of dry hours and the involuntary plan,

Grayed in, and gray. “Dream” makes a giddy sound, not strong

Like “rent,” “feeding a wife,” “satisfying a man.”

But could a dream send up through onion fumes

Its white and violet, fight with fried potatoes

And yesterday’s garbage ripening in the hall,

Flutter, or sing an aria down these rooms

Even if we were willing to let it in,

Had time to warm it, keep it very clean,

Anticipate a message, let it begin?

We wonder. But not well! not for a minute!

Since Number Five is out of the bathroom now,

We think of lukewarm water, hope to get in it.