Good Morning POU! We continue looking at Zora Neal Hurstons “Barracoon: The Last Black Cargo”. A story of the last Africans to arrive on American shores, as slaves.

Kossola was born circa 1841, in the town of Bantè, the home to the Isha subgroup of the Yoruba people of West Africa. He was the second child of Fondlolu, who was the second of his father’s three wives. His mother named him Kossola, meaning “I do not lose my fruits anymore” or “my children do not die any more.” His father was called Oluale. Though his father was not of royal heritage as Olu, which means “king” or “chief,” would imply, Kossola’s grandfather was an officer of the king of their town and had land and livestock.

By age fourteen, Kossola had trained as a soldier, which entailed mastering the skills of hunting, camping, and tracking, and acquiring expertise in shooting arrows and throwing spears. This training prepared him for induction into the secret male society called oro. This society was responsible for the dispensation of justice and the security of the town. The Isha Yoruba of Bantè lived in an agricultural society and were a peaceful people. Thus, the training of young men in the art of warfare was a strategic defense against bellicose nations. At age nineteen, Kossola was undergoing initiation for marriage. But these rites would never be realized. It was 1860, and the world Kossola knew was coming to an abrupt end.

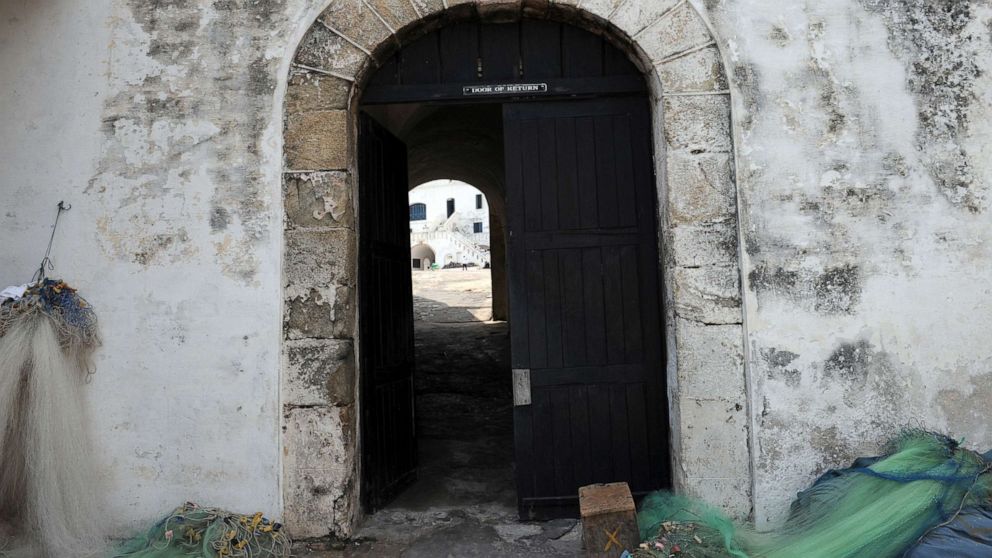

The Door Of No Return

From 1801 to 1866, an estimated 3,873,600 Africans were exchanged for gold, guns, and other European and American merchandise. Of that number, approximately 444,700 were deported from the Bight of Benin, which was controlled by Dahomey. During the period from 1851 to 1860, approximately 22,500 Africans were exported. And of that number, 110 were taken aboard the Clotilda at Ouidah. Kossola was among them—a transaction between Foster and King Glèlè. In 1859, King Ghezo was mortally shot while returning from one of his campaigns. His son Badohun had ascended to the throne. He was called Glèlè, which means “the ferocious Lion of the forest” or “terror in the bush.” To avenge his father’s death, as well as to amass sacrificial bodies for certain imminent traditional ceremonies, Glèlè intensified the raiding campaigns. Under the pretext of having been insulted when the king of Bantè refused to yield to Glèlè’s demands for corn and cattle, Glèlè sacked the town.

Kossola described to Hurston the mayhem that ensued in the predawn raid when his townspeople awoke to Dahomey’s female warriors, who slaughtered them in their daze. Those who tried to escape through the eight gates that surrounded the town were beheaded by the male warriors who were posted there. Kossola recalled the horror of seeing decapitated heads hanging about the belts of the warriors, and how on the second day, the warriors stopped the march in order to smoke the heads. Through the clouds of smoke, he missed seeing the heads of his family and townspeople. “It is easy to see how few would have looked on that sight too closely,” wrote a sympathetic Hurston.

Along with a host of others taken as captives by the Dahomian warriors, the survivors of the Bantè massacre were “yoked by forked sticks and tied in a chain,” then marched to the stockades at Abomey. After three days, they were incarcerated in the barracoons at Ouidah, near the Bight of Benin. During the weeks of his existence in the barracoons, Kossola was bewildered and anxious about his fate. Before him was a thunderous and crashing ocean that he had never seen before. Behind him was everything he called home. There in the barracoon, as there in his Alabama home, Kossola was transfixed between two worlds, fully belonging to neither.