Good Morning POU. This week we will look at the “Nadir of American race relations” (also called the Nadir of African American history) as described by historians as the period after Reconstruction through the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. A period overlooked in most history courses, as if African Americans disappeared after the end of the Civil War and popped up again at the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement.

According to historian Rayford Logan, the nadir of American race relations was the period in the history of the Southern United States from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 through the early 20th century, when racism in the country was worse than in any other period after the American Civil War. During this period, African Americans lost many civil rights gains made during Reconstruction. Anti-black violence, lynchings, segregation, legal racial discrimination, and expressions of white supremacy increased dramatically in retaliation for those gains.

Logan coined the phrase in his 1954 book The Negro in American Life and Thought: The Nadir, 1877–1901. Logan tried to determine the year when “the Negro’s status in American society” reached its lowest point. He argued for 1901, suggesting that relations improved after then. Others, such as John Hope Franklin and Henry Arthur Callis, argued for dates as late as 1923.

The term continues to be used, most notably in the books of James Loewen, but also by other scholars. Loewen chooses later dates, arguing that the post-Reconstruction era was in fact one of widespread hope for racial equity due to idealistic Northern support for civil rights. In Loewen’s view the true nadir began only when Northern Republicans ceased supporting Southern blacks’ rights around 1890, and lasted until the Second World War. This period followed the financial Panic of 1873 and a continuing decline in cotton prices. It overlapped with both the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, and was characterized by the nationwide sundown town phenomenon.

Logan’s focus was exclusively African-American and principally the American South. But the time period he identified also represents the worst period of anti-Chinese discrimination, harassment, and violence on the west coast of the U.S. (and Canada), particularly after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Why study “the nadir“

There are two places where we can count on finding African Americans in U.S. history textbooks: in discussions of Reconstruction and in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s. In the ninety-odd years that elapsed between the two events, black Americans rarely appear, save perhaps in the 1920s and 1930s, with a mention of the Great Migration or the cultural history of the Harlem Renaissance. In this simplified story, the heroes of the Civil Rights Movement arose directly from the ashes of slavery to challenge the South’s long-undisturbed system of racial oppression after World War II.

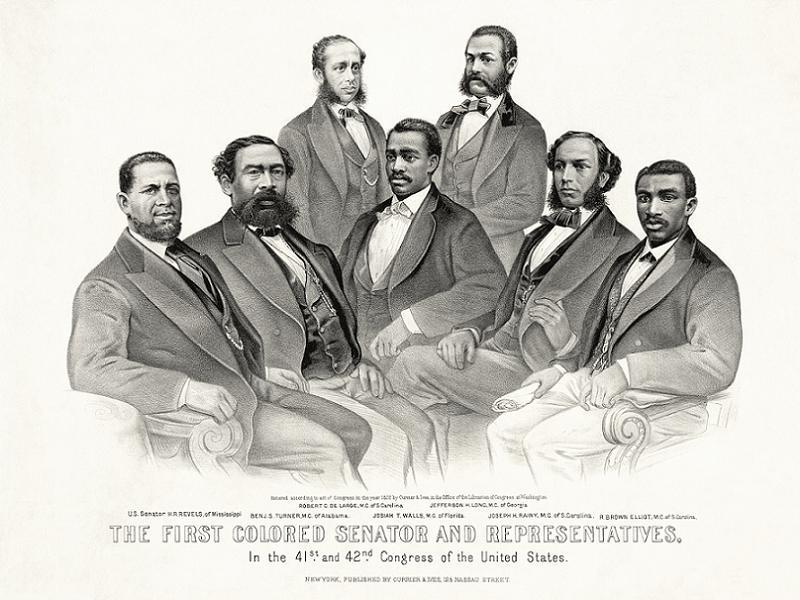

In reality, African Americans emerged from Reconstruction in the 1870s with the protection of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, and took their places as free and increasingly successful citizens in the 1880s. Because more than 80% of the nation’s African Americans lived in former slave states until well into the twentieth century, they had to exercise their new citizenship rights among ex-Confederates and their sons and daughters. During the 1880s in the South, African Americans continued to vote, serve on juries, be elected to public office, pursue education, and improve their economic status. Some white leaders accepted the outcome of losing the Civil War and the enfranchisement of the Freed people. One white man in Virginia commented in 1885, “Nobody here objects to sitting in political conventions with Negroes. Nobody here objects to serving on juries with Negroes. No lawyer objects to practicing law in court where Negro lawyers practice. In both branches of the Virginia legislature, Negroes sit, as they have a right to sit.”

Although textbooks tend to portray the history of African Americans as if not much happened between 1870 and 1954, the period was actually a long war for civil rights. White southerners continually reinvented new ways to impose white supremacy on their black neighbors. Black southerners fought back against disfranchisement and unequal treatment, the imposition of segregation, and the violent white people who perpetrated racial massacres and lynching. Because the rapidly industrializing South set up a system of racialized capitalism that left black people in segregated jobs at the bottom of the ladder, they sought the self-sufficiency of land ownership and started small businesses. Despite the onslaught of white supremacy, African Americans held hope that they would win the war for civil rights.

Since we enter a story at its end, sometimes we forget that what is past to us was future to the people whose stories we tell. Too often, what we lose in the telling is what made our subjects’ lives worth living: hope. African American’s visions of the future included equal opportunities and full citizenship, even as white supremacists took control of southern governments in the 1890s and consolidated their power in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

The period from 1890-1920, is often called the “nadir” of African American history, yet African Americans kept hope alive and forged new political weapons during this time. It may be helpful to think of southerners in 1890 as the baby boomers of the nineteenth century. Two decades after the Civil War, the southerners who came into power in that decade had been young during Reconstruction and educated after Emancipation. Members of this generation had not fought in the Civil War; nor had they been enslaved. When they came of political age, the white people were determined to find new solutions to “the Negro Problem,” and their black cohort was just as determined to win its fair share of opportunities and resources.

Tomorrow: Idealism from the generation after slavery