Good Morning POU.

We continue to look at the unsolved cases of domestic terrorism perpetrated on African-americans during the Civil Rights Era. Today we review the murder of Wharlest Jackson.

Exerlena Jackson was proud of the job promotion her husband was offered in early 1967. He’d worked 12 hard years at the Armstrong Tire & Rubber plant in Natchez, and now was being offered a position in the chemical mixing plant.

Wharlest Jackson, her husband of 13 years, told her he’d be making 17 cents an hour, enough that she could quit her job as a cook at the black school and spend more time with their five children.

Exerlena felt Wharlest deserved a step up the short, elusive ladder available only occasionally to black employees. But she was not happy about the offer. The position had previously only been held by white men, and Jackson had won it over two white co-workers.

“I begged him not to take that job,” she would say later.

She reminded him that two years earlier, their good friend, George Metcalfe, had taken a promotion at Armstrong. It happened about the time Metcalfe had become president of the local NAACP and Jackson had been named treasurer.

In late August 1965, at about noon, Metcalfe crossed the parking lot at Armstrong Tire, got in his 1955 Chevrolet and turned the ignition switch. Instantly, an explosion shattered the calm.

He suffered broken limbs, facial lacerations and burns. Pieces of skin were torn from his body and his right eye was damaged. The Jacksons had nursed Metcalfe back to health and he was able to go back to work at Armstrong a year later. No one was ever charged.

Was Wharlest Jackson next? There was good reason to worry.

Scores of black men in the post-war civil rights era had been abducted, tortured, maimed and killed by Klansmen, some of them in law enforcement, with near impunity. Investigations, most by the FBI, were piling up, unsolved and unresolved. Many of those were in Southwest Mississippi and eastern Louisiana.

In Natchez and, across the Mississippi River, in Ferriday and Vidalia, Louisiana, and in many small towns around them, the close-knit black communities knew the victims, or their families or friends, and they knew the stories.

So Exerlena Jackson knew that Metcalfe had been fortunate. He had survived. She knew that many, like arson-murder victim Frank Morris in nearby Ferriday, had not. And she likely knew that some, such as Joe Edwards, whose parents lived in Natchez, had simply disappeared.

Edwards was a 25-year-old porter and handyman who had been working at the Shamrock Motel in Ferriday for about two years when the motel’s restaurant became the meeting ground for the Silver Dollar Group in 1964.

These were Klansmen who—as the 1964 Civil Rights Act was being passed in early July—believed the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the Original Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and the United Klans of America were not aggressive enough against civil rights. They signaled their oath by carrying silver dollars minted in the year of their birth; several were in law enforcement.

Near midnight on July 12, 1964, Edwards was stopped by a police car while driving his 1958 Buick. He had spent the day shuttling his mother and siblings to and from a family barbeque, and was headed to the Shamrock. The motel had a reputation for housing prostitutes who worked at a legendary brothel in Natchez; some of Edwards’ relatives said he had been enlisted to transport the women and had crossed the racial barrier in his own sexual liaisons.

Edwards never made it to the Shamrock that night. His car was found where police had stopped it; a banker who was driving by told the FBI he had seen the law enforcement vehicle and a group of men surrounding Edwards’ car. Where Edwards went, or was taken, and by whom, was never discovered.

Three years later, the FBI was still gathering evidence that pointed to top brass inside the sheriff’s office—evidence that came from inside the sheriff’s office, from a white pastor, from the white banker. One FBI agent who worked the case recalled that his office received a report that Klansmen had taken Edwards to a remote barn, “hung him up and skinned him alive,” before they “disposed of his body.”

By 1967 when Wharlest Jackson was offered a promotion, the Southwide resistance to civil rights had become less violent. Jackson sought the opinion and NAACP field secretary Charles Evers (who had replaced his brother Medgar, who was murdered in 1963), and received encouragement to take the job.

A month after taking the promotion, Jackson worked his new dayside shift plus four hours of overtime. Soon after 8 p.m., he got in his pickup truck and headed toward home in a cold rain.

As he got near home, he put on his turn signal, triggering a massive explosion from a bomb planted below the truck frame beneath the driver’s seat.

Exerlena heard the explosion and knew instantly. “Oh, Lord,” she cried. “That’s Jackson. They got Jackson.”

The FBI investigation into Jackson’s murder generated 10,000 pages of documents that pointed to suspects, including the Silver Dollar Group. But more than four decades later, Jackson’s killers—like those who caused Metcalfe’s injuries and Edwards’ disappearance—have escaped prosecution.

A Family Torn

When the sounds of an explosion reached the Natchez, Miss., home of Wharlest and Exerlena Jackson, an 11-year-old boy tore out the back door, grabbed his bicycle and peddled the 150 yards to Minor Street where he would find his father’s truck, contorted by a bomb.

“I saw a lot of metal twisted and tangled and torn to pieces,” Wharlest Jackson Jr. recollected of the 1967 incident. “I saw blood from the parts of him that were still in the truck. That is painted into my memory.”

Wharlest Jr. remembers that February night, 45 years ago, when his dad made a left turn on his way home. His father dutifully had used his signal light prior to the turn. That triggered a bomb placed below his seat.

The younger Jackson now lives in the same house he and his sisters grew up in, and he looks out the same kitchen window where his family gathered to peer into the dark on the night their father was killed. His mother, who was lying in bed, had a good idea of what just happened. “Oh, Lord, they got Jackson,” she cried out when she heard the explosion, using her nickname for her husband.

He remembers the fear of the Ku Klux Klan, and the unspoken message the black community heard louder than the explosion on Minor Street.

Denise Ford, Wharlest Jr.’s sister, also remembers being packed into the car and driving to find the wreckage of Wharlest Sr.’s truck. She remembers going to the hospital, and how Exerlena Jackson followed drops of blood on the floor to her husband’s hospital room, where she was denied access and told to go home.

Ford and Wharlest Jr. recall threatening phone calls that followed, and the way their mother reminded the children to watch their backs and be aware of their surroundings, even before the Klan killed their father, ostensibly for taking a supervisor’s position at the Armstrong Tire Company manufacturing plant in Natchez, a position heretofore not held by a black man. Local racists also did not like the fact that Jackson was involved with the Natchez branch of the NAACP.

His own family did not want him to take the new position for fear of violent reprisals.

“Our mother and father sheltered us from that,” Wharlest Jr. said. “What we saw, we learned from other people. We knew about boycotts, the marches and imprisonment. We also knew our father was involved with the NAACP.”

Even when Wharlest Jr. went to college at Mississippi State University, where he released anxiety and frustration on the football field, his mother feared for his safety.

“I don’t know that I feel safe now,” Wharlest Jr. said. “9/11 made me stop fearing the Klan. That’s when I thought, they were the real terrorists because they had installed a greater fear in all of us.”

The Jackson family has yet to find closure, let alone justice, for the murder of Wharlest Sr. Though they are certain of the Klan’s involvement, no individual or group has been marked responsible for killing their father. “I believe that a FBI agent came around to [Exerlena] and told her that they knew who it was, but it was up to the local authorities on what to do,” Ford said. “And nobody did nothing.”

Wharlest Jr. said it was a secret, but one which some members of the white community and African-American communities knew, though no one came forward. For him, the speculation blurred the line between truth and lies.

The investigation into the 45-year-old case is detailed in thousands of pages of FBI documents opened this fall by the National Archives at the behest of LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication Unsolved Civil Rights-Era Murders Project which had filed Freedom of Information requests two years ago. The evidence points to several now-deceased Klansmen from Concordia Parish, La., some of whom worked with Jackson Sr. at the Armstrong Tire Co.

“For a long time it didn’t matter to me who (the killers) were,” Wharlest Jr. said. “It mattered to me that I had to forgive them for what they’d done to our father. That’s the way to release myself. I was in a cage because of forgiveness. My life was a wreck; it went through drugs, cocaine and everything I went through with our father’s death. I thank God now I’ve been able to get my life back together.”

The son said he was haunted by the images of his father’s body he saw as a boy, which led to post-traumatic stress and a life scarred by the memory of a good father, known for his lighthearted teasing and dedication to his family, a father who was gone too soon.

“I have seen an explosion on the TV and it upsets me,” Wharlest Jr. said, tears sliding down his cheek as Ford lowered her head in grief. “I’ve seen a commercial where a candy thing just kind of explodes. And it kind of upset me.”

But life goes on, according to Wharlest Jr., who has lived in Dallas, Jackson, Miss., Los Angeles, Florida, New York and New Orleans. He said he heard the voice of God 10 years ago, telling him to return to Natchez.

Though he agrees race relations have improved in Natchez, he said some hatred has been passed down the generations, and Klansmen who once wore white sheets and hid their identity to the public now openly denounce diversity, face to face. Laws against hate crimes discourage violence, but Wharlest Jr. said bitterness still exists between the races.

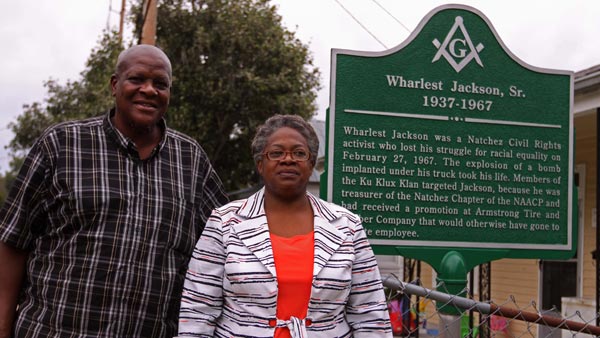

Wharlest Jr. and Ford, with help from members of the community, have placed a memorial sign in the spot where the bomb went off, and a well-attended unveiling was held.

“I lost my dad,” Wharlest Jr. said. “And to know that he sacrificed his life for his wife and children. Throughout the years, people actually forget about the people who sacrificed their lives for us to make this community better place.”

Wharlest Sr.’s children believe their father has left behind a legacy of sacrifice and hope for a better life for future generations, and they remember him as a man of integrity and infinite love.

“He used to come home from work, we used to play jacks on the front porch,” Ford recalled. “My dad was a lovable, funny person…To me he was a true dad and husband.”