Good Morning POU!

Today’s feature in our Women In The Negro Leagues series should have a movie made of her life! A mini-series even!

Effa Manley

Business woman. Community leader. Socialite. Baseball executive par excellence. Keeper of the Negro Leagues’ flame. Hall of Famer. Throughout her lifetime Effa Manley wore all these hats and more, but none more proudly than that of her beloved Newark Eagles, the Negro National League franchise that she and husband Abe Manley owned and operated from 1934 until 1948. The Most Famous Woman in Baseball, Bob Luke’s biography of her, shows us how Effa left her indelible mark on the Eagles, the community of Newark, and the game of baseball.

Manley’s racial background is not completely known. It has been written her biological parents may have been white, but she was raised by her black stepfather and white mother, leading most to assume her stepfather was her biological father and therefore to classify her as black. Daryl Russell Grigsby wrote, “…some insist she was a white woman exposed to black culture, who identified as black. Regardless of her ethnic origins, Effa Manley thought of herself as a black woman and was perceived by all who knew her as just that.” Author Ted Schwarz wrote, “She was a white woman who passed as a black…She could stay in any hotel she desired.”

According to the book The Most Famous Woman in Baseball by Bob Luke, Effie was born through an extramarital union between her African American seamstress mother, Bertha Ford Brooks, and Bertha’s white employer, Philadelphia stockbroker John Marcus Bishop; therefore she may actually have been of mixed heritage.

In an interview she gave, she seemed to enjoy the confusion her skin color created. She related a story of when her husband, Abe Manley took her to Tiffany’s in New York for an engagement ring. She picked out a huge five-carat stone. She remarked at how every salesgirl in the store was on hand to get a glimpse of this “old Negro man buying this young white girl a five-carat ring” and how she got a kick out it.

Following this extramarital union, Effa’s mother and her first husband divorced, and she soon remarried an African-American man. Effa was thus raised in an African-American family alongside five black step-siblings.

Early in her life she identified as white, sometimes using it to her advantage to gain employment in shops that didn’t hire African-Americans. That said, she was still thoroughly a member of the black community in her social and family life, and would later become active in racial causes in the city of Newark.

Abe Manley, Effa’s future husband, hailed from Hertford, North Carolina. As a young man he made his way up the Eastern seaboard working a variety of jobs before settling in Camden, New Jersey, where he began making serious money running numbers. He became treasurer of the Rest-A-Way Club, Camden’s all-purpose social club for the city’s Negro elite, an establishment with an $8,000 piano and poker pots worth twice that much. In 1932 a bombing of the club led Abe to relocate to Harlem where he began courting Effa. In the summer of 1933 they were married, Abe lavishing his new bride with a five-carat ring, mink coats, and other luxuries.

Both Abe and Effa grew up loving baseball, and Abe had briefly owned a ballclub, the Camden Leafs, for part of the 1929 season. With his large bankroll and an enthusiastic business partner in Effa, Abe applied for and won a franchise in the Negro National League in late 1934. He and Effa became owners of the NNL’s Brooklyn Eagles, but before getting to work building the team, they turned their attention to league matters at the owners’ meeting of January 1935.

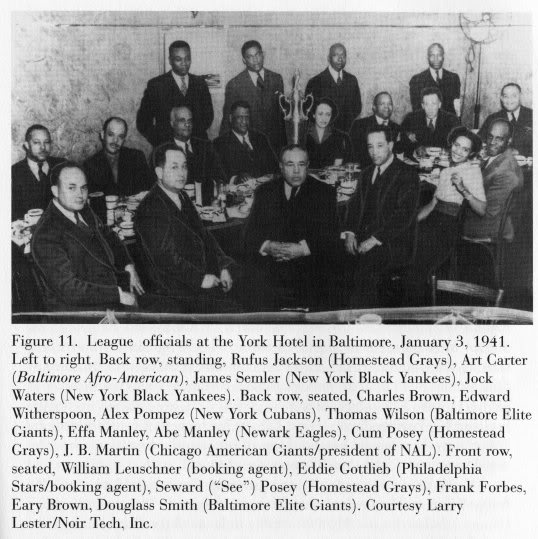

In the biography, of Effa, Bob Luke describes in detail the pressing financial and organizational issues that faced the owners: adopting a constitution, preventing players from breaking their contracts for better offers overseas, protecting umpires from abuse, and establishing a central league office. As would become a theme of NNL owners’ meetings though the years, the proceedings were acrimonious and not always productive. The strong-headed Effa frequently found herself at odds with fellow owners like Cum Posey of the Homestead Grays and Tom Wilson of the Baltimore Elite Giants, particularly with regard to the the appointment of an impartial, outside party as commissioner.

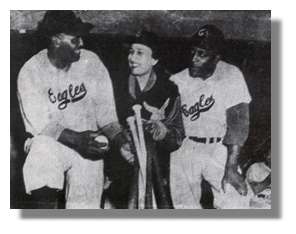

Effa and Abe worked out distinct roles in managing the Eagles, their division of labor reflecting their personalities. Effa, the more vociferous partner, handled much of the player negotiations and was the primary public face of the team. Abe was quieter, more reserved, and concerned himself with player evaluation and trades. As the financier behind the operation, Abe also exerted more influence over big-picture financial decisions, like departing the crowded New York City baseball market for neighboring Newark, New Jersey following the 1935 season. Abe bought the Newark Dodgers and combined their roster with that of his Brooklyn Eagles. They were christened the Newark Eagles, and in the spring of 1936 they began play at Newark’s lighted Ruppert Stadium.

“The Manleys were a very unusual combination,” says Monte Irvin. “Mrs. Manley was a very astute businesswoman and she became very knowledgeable about baseball affairs.”

She took over day-to-day business operations of the team, arranged playing schedules, planned the team’s travel, managed and met the payroll, bought the equipment, negotiated contracts, and handled publicity and promotions.

Fellow owner Cumberland Posey of the Homestead Grays once wrote that “Negro baseball owners can take a few tips from the lady member of the league when it comes to advertising.”

Thanks to her rallying efforts, more than 185 VIPs — including New York Mayor Fiorello LeGuardia, who threw out the first pitch, and Charles C. Lockwood, justice of the Supreme Court of the State of New York — were on hand to watch the Eagles’ inaugural game in 1935. But the Eagles proved unable to rise to the occasion, and dropped the opener to the Homestead Grays, 21-7.

George Giles, the Eagles first baseman at the time, recalled that Manley did not take the loss well.

“The Homestead Grays near killed us! … Mrs. Manley left (the ballpark),”said Giles. “When she was displeased, the world came to an end. She’d stop traffic. …

“Mrs. Manley loved baseball, but she couldn’t stand to lose. I was a pretty hard loser myself, but I think she’d take it more seriously than anybody.”

So seriously that she was unwilling to suffer it for long. When the Eagles finished with a losing record that first season, Manley insisted that manager Ben Taylor be fired and replaced with Giles. Giles said Abe Manley approached him and told him, “My wife wants you to manage the ballclub.”

Luke explores every aspect of Effa’s role with the team, including her romantic involvement with several Eagles players. Although she loved Abe, and remained married to him until his death in 1952, that didn‘t stop her from having relationships with ball- players. Terrie McDuffie, a young hurler with a wide array of pitches, was one of Effa’s lovers, and Luke notes that “she ordered [Eagles’ manager George] Giles to start McDuffie for games when she wanted to show him off to her lady friends.” About a decade later, when trying to recruit Monte Irvin to return for the 1946 season, Effa met him at home wearing just a negligee and invited him in, saying, “Abe won’t be back until tomorrow.” To his credit, Luke doesn’t sensationalize this aspect of Effa, and makes note of other times when she showed concern for players in completely non-romantic ways. She helped former Negro Leaguers like George Crowe break into Major League Baseball, served as godmother to Larry Doby’s first child, and helped other former players land jobs or make down payments on a first home.

As busy as Effa was with the Eagles, she was passionate about social issues, the nascent civil rights movement, and supporting the war effort. While living in New York in the early 1930s, she led boycotts of Harlem businesses which served mostly black customers without employing any African-American employees. After six weeks, the owners of the store (Blumstein’s Department Store) gave in, and by the end of 1935 some 300 stores on 125th Street employed blacks. Manley was the treasurer of the Newark chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and often used Eagles games to promote civic causes. In 1939 she held an “Anti-Lynching Day” at Ruppert Stadium. In Newark, Effa continued to push for reform of Jim Crow segregation, while also creating a haven for African-Americans at the ballpark. As she wrote in a letter to sportswriter Wendell Smith, “The important thing is large crowds of Negroes have somewhere to go for healthy entertainment.”

At this time most blacks were barred from practicing medicine. The Booker T. Washington Community Hospital, which offered training for colored doctors and nurses, opened due in a large part to money raised from the Newark Eagles. They played numerous benefit games to raise money for new medical equipment. They also raised money for black Elks lodges, a major part of urban black social life. The Eagles worked especially hard for groups that promoted the welfare of Newark’s black population. In an exhibit honoring the Negro leagues at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, there is a banner given to the team by the Newark Student Camp Fund in recognition of their efforts to help the community. Another example of the relationship Effa helped forge with the community was copying a practice of another team which allowed the city’s youth to attend games for free. Some children could afford the ten cent fare for the bus ride while others jump on the back of a moving bus to take advantage of the free ballgames. Because of Effa Manley, the Newark Eagles were as important to black Newark as the Dodgers were to Brooklyn.

Luke paints Effa as a reformer in all areas of her life. She was someone who saw possibility and then set out to achieve it, whether that meant creating better professional opportunities for blacks in Newark, ensuring that the Negro National League operated in a more transparent manner, or creating a better performing and more profitable ballclub within the confines of Ruppert Stadium. In the offseason of 1945–46, after years of playing second fiddle to the Homestead Grays, Abe and Effa redoubled their efforts to bring a championship to Newark.

The ’46 season began auspiciously with an opening day no-hitter from Leon Day, who was making his first start after three years in the Army. The war years had been hard on the Eagles’ line-up, as they lost about a dozen players to the draft, but at the gate it was a different story, with the war-time economic boom producing healthy attendance figures. Effa knew the team would be poised for a pennant run, with its coffers well stocked from the last few years and its roster augmented by returning stars like Day. Sure enough, the Eagles took the NNL by storm, capturing the first-half pennant, and after a brief June swoon, rebounding to take the second-half crown as well. Monte Irvin paced the club with a .389 average, and they advanced to face the Kansas City Monarchs, champions of the Negro American League, in the World Series.

The series went the distance and was contested in not two but four different ballparks: Ruppert Stadium for games two, six, and seven, the Polo Grounds for game one, Kansas City’s Blues Stadium for games three and four, and Chicago’s Comiskey Park for game five. The Eagles emerged victorious in the seventh game, helped by home-field advantage but also by the absence of Monarchs’ stars Satchel Paige and Hilton Smith, who had left the team before game seven to join a barnstorming tour. Abe and Effa rewarded their championship ballclub with diamond rings and a new $15,000 luxury bus. Meanwhile, the Satchel Paige All-Stars held their own against the Bob Feller All-Stars (a team made of MLB’s best), a surprising achievement since Paige’s team lacked such stars as Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Irvin, and Doby. To open-minded baseball observers, it was becoming abundantly clear that the stars of Negro ball could hold their own against major league competition.

Effa achieved another goal during the following offseason, when a non-owner commissioner, the Rev. John H. Johnson, was finally appointed to oversee the Negro Leagues. He drafted a new constitution that limited World Series venues to the two cities competing, included more protections for players and umpires, and re-affirmed a five-year ban on players who jumped their contracts to play abroad. But just as the Negro Leagues were becoming better organized, the foundation of the league, its most talented players, was starting to slip away. First went Jackie Robinson to Branch Rickey’s Brooklyn Dodgers. Then an Eagles’ star, Larry Doby, followed suit by signing with Bill Veeck’s Cleveland Indians. While Veeck compensated the Eagles to the tune of $15,000 (a figure Effa negotiated), many other Negro League stars would be signed away to the majors without their old clubs getting any compensation. In any case, money couldn’t buy players of the same skill level or cachet as those departing to MLB. As Luke keenly observes, these were times of mixed emotion for Effa and others who loved Negro League baseball and made it their life’s work. While it was rewarding to see black players finally integrate, and thrive in, the major leagues, it was equally painful to witness the decline of the Negro Leagues.

It all happened relatively quickly. Following the 1948 season, Effa and Abe’s Eagles, along with the Grays and the New York Black Yankees, opted to disband. They sold the team for the paltry sum of $15,000 (the same amount Abe had ponied up for the team’s new bus just two years earlier), and the new owner relocated the club to Houston. Without the Eagles in her life, Effa stepped up her involvement in the local Newark NAACP chapter, becoming its treasurer. Baseball was still at her core though, and she remained as outspoken as ever. Effa condemned the way major league teams had raided the Negro Leagues of their top talent and did what she could to keep the collective memory of Negro baseball alive. As journalist Wendell Smith, her sometimes adversary, noted, she was “trying to fight off the inevitable and cling to the great days.”

Unfortunately for Effa, while integration came to MLB’s clubhouses in 1947, it would be decades before African-Americans had any real positions of influence within its executive halls. Some great baseball minds, like Effa and Abe, or John and Billie Harden of the Atlanta Black Crackers, were left on the outside looking in, with no role available to them in organized baseball.

In 1977, Manley was interviewed for an oral history project which is archived at the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries and is available online.

In the spring of 1981, her health had deteriorated to the point that she could no longer live in her apartment. She moved into a rest home run by former Negro league player Quincy Trouppe. She told Trouppe that she would go to the hospital to get checked out, even though the ambulance drivers did not think she was ill enough to go to the hospital. She had cancer of the colon, which progressed into peritonitis after surgery. She had a heart attack and died on April 16, 1981, having never returned to the rest home. She died just four days after the boxer, Joe Louis, her sports idol, who had been one of the most influential black athletes of that time.

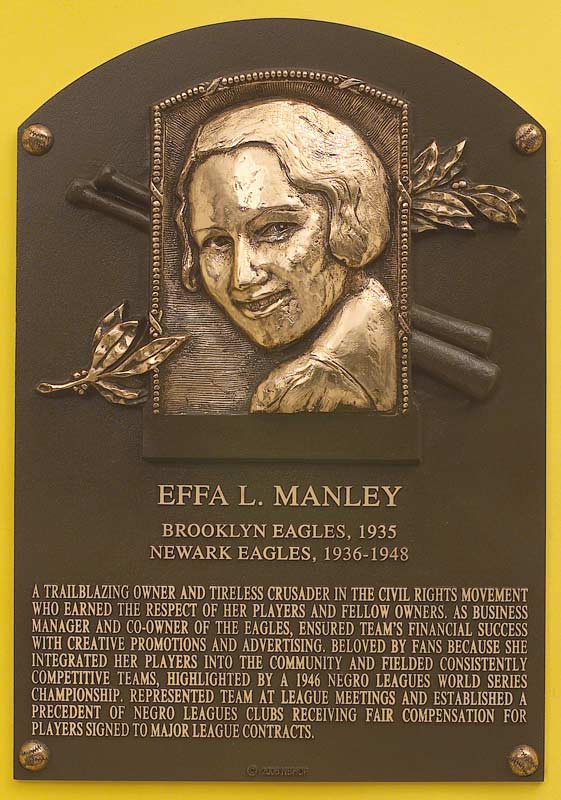

In 2001, the Baseball Hall of Fame formed a special committee of Negro Leagues scholars to examine the records of former players and the contributions of influential owners. Effa Manley was among the select group of past executives chosen for induction. In 2006, twenty-five years after her passing, she was enshrined in Cooperstown, the Hall’s first female inductee.