We continue our look at the history of African Americans in the Communist Party.

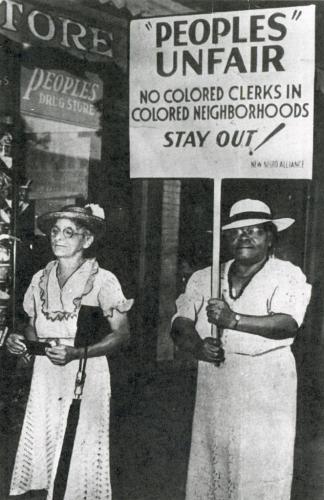

During the period from 1928-1935, The Communist Party of the USA made a point of campaigning against racial segregation. The CPUSA organized among African Americans in the North on local issues; it was, for example, either the first or one of the most active organizations in campaigning against evictions of tenants, for unemployment benefits, and against police brutality. In other instances during this period, the Communist Party joined in existing campaigns, such as the economic boycott, under the slogan of “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work,” launched against Jewish and Italian businesses in Harlem that refused to hire African-American workers.

The party’s relations with other groups in the black community was volatile during this period. The rigid communist orthodoxy dictated by the Comintern required the party to attack other, more moderate organizations which also opposed racial discrimination. During the late 1920s, the CPUSA denounced the NAACP and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters as “class enemies” or “class collaborators”.

In 1935, the Comintern abandoned the militancy of previous years in favor of a Popular Front, which sought to unite socialist and non-socialist organizations of similar politics around the common cause of anti-fascism. This confirmed its policy. The party had mended its relations, at least temporarily, with groups such as the NAACP and had developed relations with church groups, particularly in the North. The party had also started edging toward support of the New Deal by moderating its attacks on the Roosevelt administration, which had promoted programs alleviating the most severe economic problems.

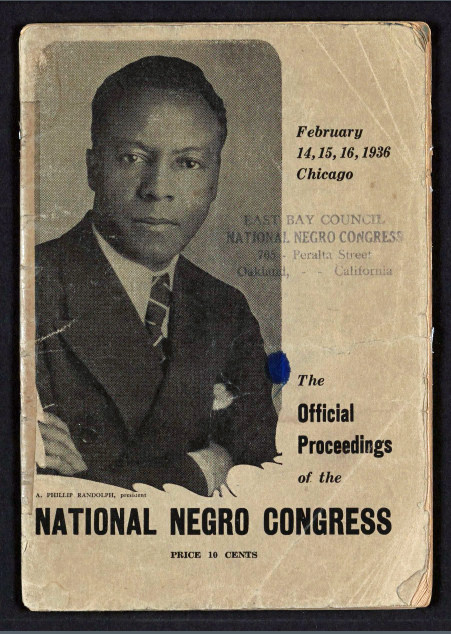

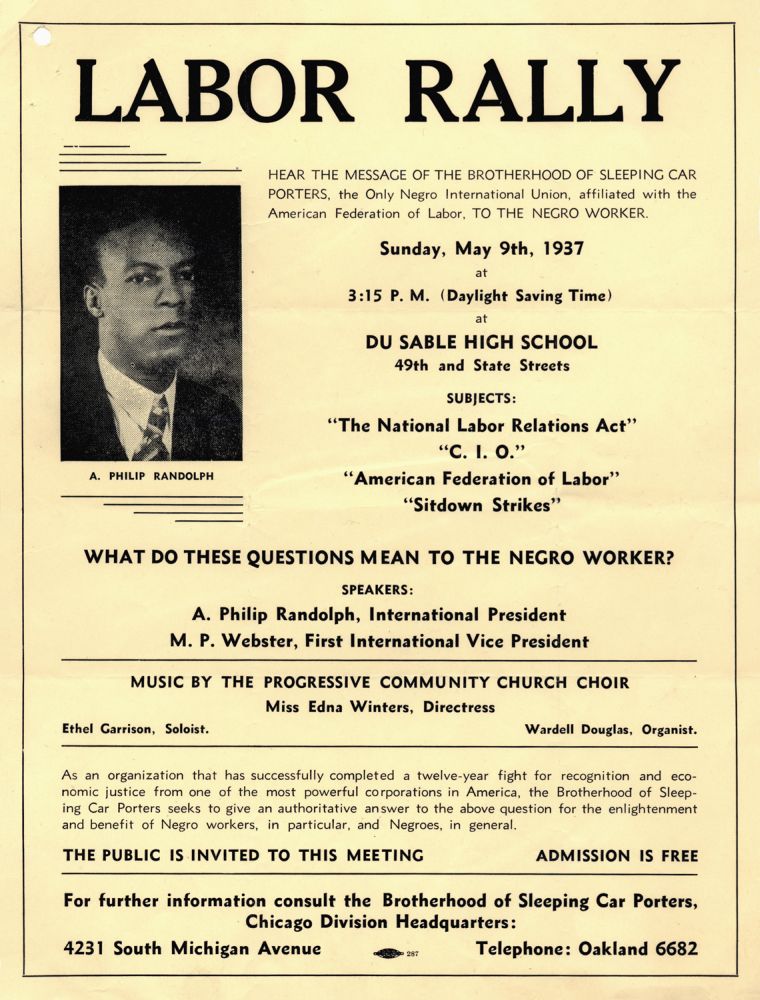

As a sign of its new approach, the CPUSA folded up the League of Struggle for Negro Rights and joined with other non-communist groups to create a new organization, the National Negro Congress. A. Philip Randolph, a longtime member of the Socialist Party and founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, served as its head. The NNC functioned as an umbrella organization, bringing together black fraternal, church and civic groups. It supported the efforts of the CIO to organize in the steel, automobile, tobacco and meat packinghouse industries. The NAACP kept its distance from the NNC, whose leaders accused the organization of ignoring the interests of working-class blacks.

National Negro Congress

The National Negro Congress (NNC) was formed in 1935 at Howard University as a broadly based organization with the goal of fighting for Black liberation; it was the successor to the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, both affiliated with the Communist Party USA. During the Great Depression, the party worked in the United States to unite black and white workers and intellectuals in the fight for racial justice. This period represented the Party’s peak of prestige in African-American communities. NNC was opposed to war, fascism and discrimination, especially racial discrimination.

Historically, many black workers were segregated and more often than not, racially discriminated in the labor force. In order to combat racism within their respective jobs, they had to establish a union. However, many of the unions around the depression era had exclusively white members, excluding African Americans from their protection and benefits. Black workers took initiative to unite against racism and classism.

The foundation of the National Negro Congress was a response to the historical oppression African Americans faced in the United States, in particular in the workforce. Given that black workers have been historically marginalized by being exploited from the time when they were slaved, the National Negro Congress advocated for black liberation through the many sectors of the African-American life. Forging alliances with organized labor, the Communist Party, and even mainstream civil rights groups, the NNC not only drew on the talents and resources of a cross section of organizations but also established a blueprint for subsequent generations of black activists.

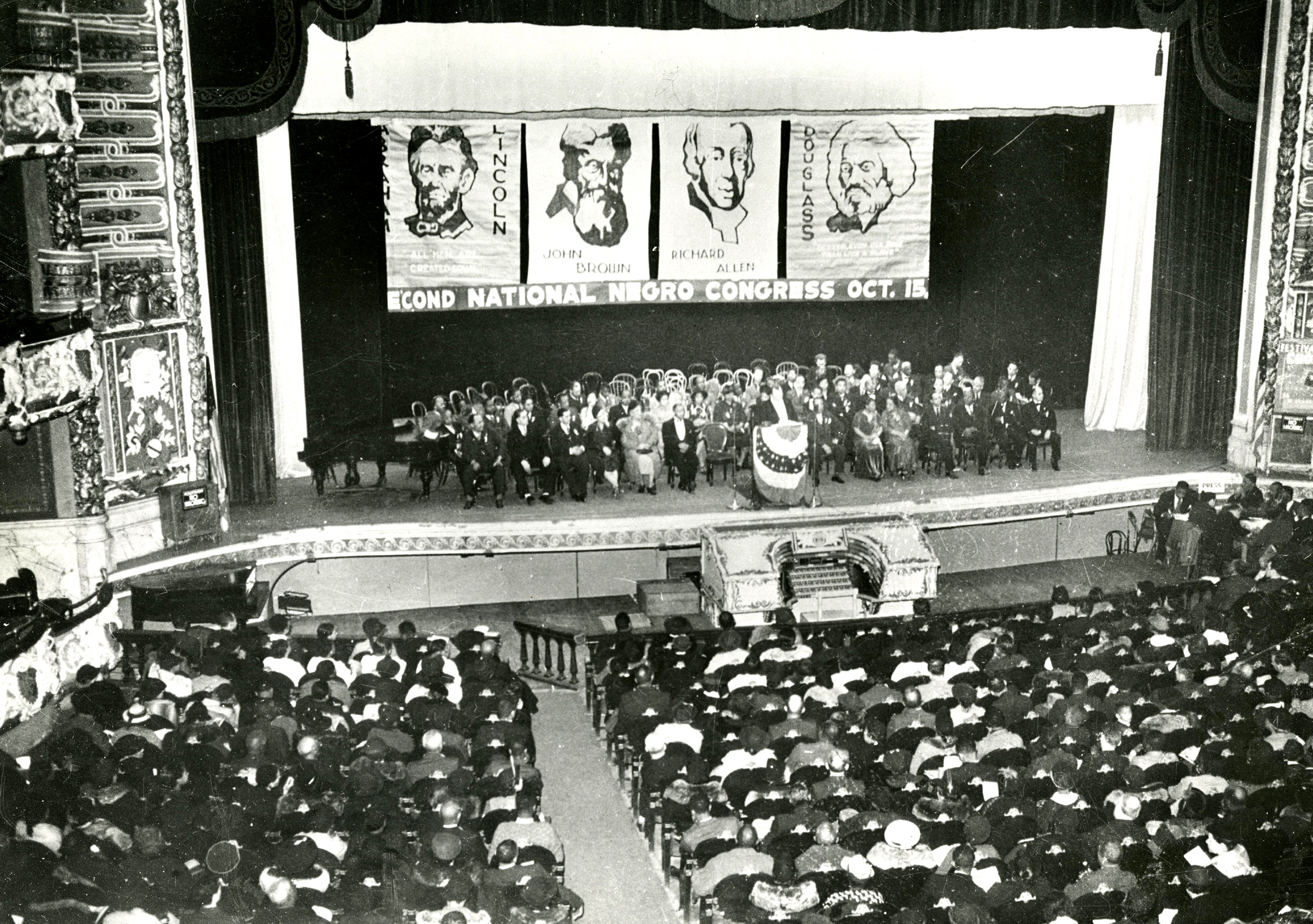

Participants included intellectuals from Howard University, civic and civil rights leaders, labor leaders and religious groups. White participation was not excluded. Black workers affiliated with the National Negro Congress advocated for integration into the larger and better funded unions such as the CIO. Although the CIO supported the foundation of the National Negro Congress to fight for civil rights and against racism, the communist aspect of the Congress deprived both organizations from having strong ties to each other: “During the late 1930s and 1940s, despite the efforts of the National Negro Congress and others, reactionary forces operating in the interest of capital increased their attacks on the CIO. The most backward anti-Communist propaganda was directed at the CIO. This was made more complex by organized labor’s positive relationship with Franklin D. Roosevelt and its support of his policy concerning World War II.”

There developed a division between those who supported communism, including its fight on behalf of African Americans, and those who only supported civil rights. With the loss of support from the CIO and AFL, African Americans were excluded from major unions. With the emergence of the National Negro Congress, the African-American community found refuge with activists identifying as communist. Even with having a safe space to discuss about class struggle, Black workers did not have any radical union that took a stand against capital within the race framework. In spite of not having the support of AFL-CIO, they relied upon the militancy and communist-led organization of the NNC. Aside from challenging the concept of racism, members of the National Negro Congress advocated against the fascism abroad and the new deal in the United States.

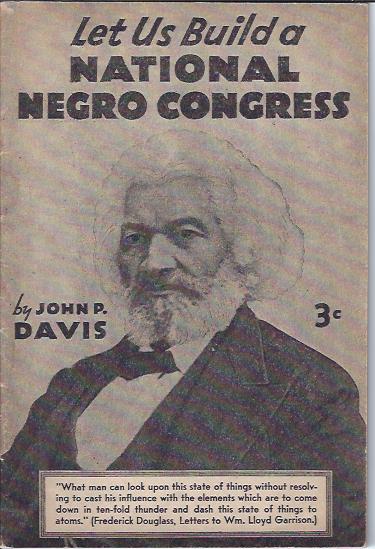

The election of Franklin D. Roosevelt resulted in a huge economic, political and social reform over the succeeding years. With the implementation of the New Deal, many African Americans in the North believed they had elected a new leader whose ideas were seemed radical. However most of these programs did not have any say or input of the African-American community. Therefore, most of the struggles that were faced for being black in the United States were neglected: On a whim, activist John Davis attended President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first National Recovery Administration hearing and noticed, in disbelief, that no one represented the interests of African-Americans. He contacted his friend Robert C. Weaver, another Harvard University graduate, and formed the two-man Joint Committee on National Recovery in 1933, challenging Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. The two were determined to become the first full-time lobbyists for civil-rights in American history. They traveled the back roads of the deep and dangerous – for a black man – South. They investigated lynchings, voting rights violations of black Americans, and the squalid working conditions of black agricultural, textile and factory workers.

Because of extensive disenfranchisement of African Americans in the South, the powerful Southern Block in Congress represented only their white constituents. The black community from different sectors of the community began to form their own institution to address issues that pertain within the black experience. The National Negro Congress consisted mainly of Blacks, but not exclusively.

In the course of discussions at the Joint Committee on National Recovery’s (JCNR) conference in May 1935 on the economic status of African Americans under the New Deal, John P. Davis and Communist Party activist James W. Ford expressed the need to consolidate the strength of disparate organizations dedicated to fighting racial discrimination. The JCNR conference concluded by forming a committee of sixty prominent activists charged with organizing a National Negro Congress the following year.

In February 1936, the first national meeting of the Congress was held in Chicago. It was a confluence of civic, civil rights, labor, and religious groups from across the nation; over 800 delegates representing 551 organizations and over 3 million constituents attended. A. Philip Randolph was elected President and John P. Davis was elected National Secretary. In keeping with their Popular Front orientation, the Communists in attendance did not attempt to hide their affiliation but consciously deferred to non-Communist delegates.

The National Negro Congress validated the struggle and existence of Black Americans in the United States. Noticing that the National Negro Congress was drifting into left-wing sectionalism, Randolph reinforced the tradition of prioritizing the black community first above organizations and ideologies. He rejected NNC affiliation with both major parties, the Communist Party, the Socialist Party and with the Soviet Union. None, he noted, placed the interests of Negroes “first”. The interests of numerous radical parties were not founded in the principles of race. As a matter of fact, they only saw class struggle as a problem for Americans. This negligence of race further deprived many African-Americans from amplifying their voice about their experience in the labor-work force.

Randolph believed that the National Negro Congress should never be subjugated or controlled by the Communist party for their own advantage: “Appealing to the Congress, he asked for a leadership that would be ‘free from intimidation, manipulation or subordination… a leadership which is uncontrolled and responsible to no one but the Negro people.” With no tying to any political affiliation, Randolph wanted the National Negro Congress to be free from any biased decision regarding the African-American struggle. By being independent from any political party, he wanted to create a space for grassroots organizing. “The interest of the people should come from the people” said Randolph. Although he advocated for the integration of black workers to the AFL-CIO, Randolph wanted the National Negro Congress to be a separate entity; a space where black workers from the AFL-CIO can use for their affirmation of their struggle as a black working class.

Despite lingering suspicion of Communist involvement, NNC delegates were able to agree on a broad program emphasizing the rights of African Americans to fair employment and housing, union membership and educational opportunities, an end to police brutality and lynching, bringing black laborers together in unions such as the Congress of Industrial Organizations, and international and interracial solidarity against fascism. Over the next few years, local NNC chapters in Harlem, Chicago, and elsewhere became locus points for broad-based community activism against racial discrimination.

The signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (Nazi-Soviet Pact) in 1939 signaled the beginning of the end for the NNC and damaged its reputation significantly in the black community. A. Philip Randolph resigned from the Negro National Congress in protest and black newspapers throughout the North condemned the party. The CPUSA attacked its opponents as warmongers. When Adolf Hitler’s forces invaded the Soviet Union, the party switched to an all-out support for the war effort. It denounced Randolph’s proposed March on Washington against employment discrimination in war industries, arguing that it might harm production. The Cold War further undermined support for the Communist Party in black communities and crippled the NNC as a movement vehicle.