HAPPY HUMP DAY, P.O.U.!

We continue our series on African American Hoteliers…

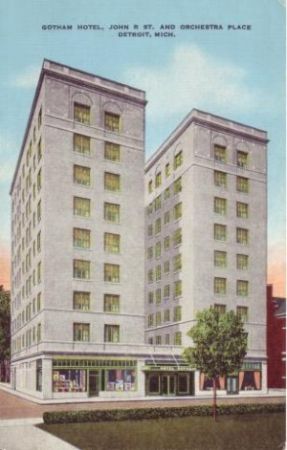

THE GOTHAM HOTEL

Detroit, Michigan

Detroit’s Gotham Hotel exuded glamour

RoNeisha Mullen and Dale Rich

February 3, 2011 at 1:00 am

Sitting on the edge of Detroit’s downtown district, the Gotham Hotel was a shining example of the city’s glamour.

The twin-towered hotel at 111 Orchestra Place offered a décor and service that rivaled that of the country’s fanciest hotels.

But there was something about the Gotham besides its magnificent fixtures and cream-of-the-crop clientele that set it apart from other first class hotels in the city.

It was black-owned.

“It was the pride of Detroit and black America. They advertised it everywhere,” said Edward Vaughn, a former state representative and professor of African-American history at several area universities.

“I knew all about the hotel at 111 Orchestra (Place) before I even got to Detroit.”

The nine-story, 200-room inn one block north of Mack and John R was built in 1925 by Albert Hartz for his personal residence.

In 1943, Hartz sold the hotel to John J. White and Irving Roane, two Detroit black businessmen, for $250,000. They turned it into a social center for Detroit’s black community.

Black people were especially proud of the Gotham because it gave them the opportunity to patronize a superior hotel of their own. At its peak, it had 1,000 guests a week.

Famous guests included Olympic great Jesse Owens, author Langston Hughes and civil rights activist and later Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and entertainers Ella Fitzgerald, Sammy Davis Jr. and Duke Ellington.

On the local front, heavyweight boxing champ Joe Louis often could be found in the Ebony Room, the hotel’s restaurant, eating breakfast.

Bow-tie wearing waiters served meals of “tunaflake cocktail lamaze” and “roast dindonneau turkey with oyster stuffing” in the Ebony room, named after Ebony magazine.

Gwen Estes Jones, a former Detroit resident who now lives in Pontiac, remembers visiting the Ebony Room in the 1950s with her husband, Claude Estes.

“There weren’t any black (owned) restaurants that equaled the Gotham,” said Jones, 78. “It was as close to five-star as blacks could get. It was like a step up in life.”

Rooms cost $3-$5 a day and suites, which featured solid mahogany furniture, cost between $7-$8 a day.

The Gotham also featured a drugstore, barbershop and permanent apartments for Detroit’s rich.

Maxine Powell, co-founder and instructor for Motown Record’s in-house finishing school, lived at the Gotham and worked as a manicurist at the hotel in the 1940s, before opening her own finishing and modeling school.

The Gotham ceased its hotel operations in September 1962 after falling on hard times. In November, the building, which had become an illegal gambling den, was raided by more than 100 federal, state and Detroit police officers in what some African-Americans called “Negro removal,” in which blacks were uprooted from the more prominent areas of Detroit.

Police broke down every door in the 200-room hotel, smashing a gambling operation that netted as much as $30 million a year, according to news stories.

“I don’t think there was any reason for it, other than they wanted to move us out of that area,” said Vaughn. The raid “was just the best way for them to do it.”

The building on Orchestra Place was razed in 1963.

Almost 40 years after the Gotham was demolished, a parking lot and deck were constructed on the land.

White died in 1964 awaiting trials on federal gambling charges related to the numbers operation at the hotel.

The old Gotham hotel is gone, but its legacy is often resurrected in documentaries, books and stage plays based on Paradise Valley and the “finest Negro hotel in America.”