Good Morning POU!

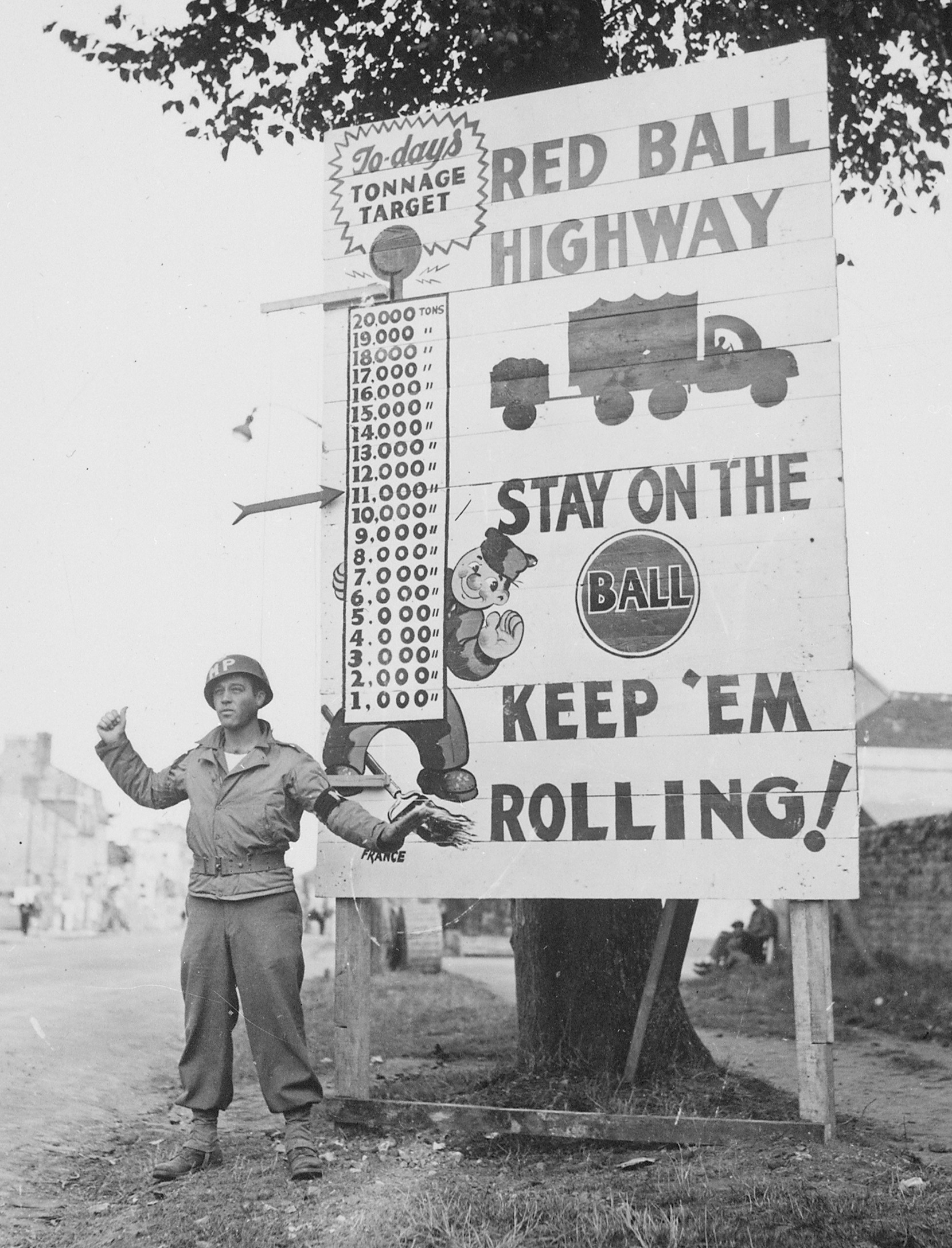

Today’s feature is about the Red Ball Express.

“When Gen. Patton said for you be there, you were there if you had to drive all day and all night. Those trucks just kept running. They’d break down, we’d fix them and they’d run again,” said James D. Rookard, a truck driver with the famous World War II Red Ball Express.

Army Gen. George S. Patton’s bold armored advance across France in 1944 is credited historically as a significant contribution to the Allied victory in Europe in World War II. The Allied breakout from Normandy and the French hedgerow country in the summer started a race to Paris and points north and east. Patton stretched his supply line to near-collapse.

Since an army without gas, bullets and food would quickly be defeated, the Army Transportation Corps created a huge trucking operation called the “Red Ball Express” on Aug. 21, 1944. Supply trucks started rolling Aug. 25 and continued for 82 days. Men like Rookard, then 19, played a major role in the Nazis’ defeat by ensuring U.S. and Allied warfighters had what they needed to sweep across France into Germany.

Nearly 75 percent of all Red Ball Express drivers, like Rookard, were African American. That’s because well before and during the war, U.S. commanders in general believed African Americans had no mettle or guts for combat. Consequently, the Army relegated blacks primarily to “safe” service and supply outfits and the Navy assigned them as mess stewards. All Marines are combat troops — the Corps refused to take blacks at all until 1942.

“Red Ball Express” was the Army code name for a truck convoy system that stretched from St. Lo in Normandy to Paris and eventually to the front along France’s northeastern borderland. The route was marked with red balls. On an average day, 900 fully loaded vehicles were on the Red Ball route round-the-clock with drivers officially ordered to observe 60-yard intervals and a top speed of 25 miles per hour.

At the Red Ball’s peak, 140 truck companies were strung out with a round trip taking 54 hours as the route stretched nearly 400 miles to First Army and 350 to Patton’s Third. Rookard recalled convoys rolling all day every day regardless of the weather. Night driving was hard because of blackout rules.

“We had to drive slowly at night because we had to use ‘cat eyes,’ and you could hardly see,” he said. “If you turned on your headlights, the Germans could bomb the whole convoy. So we had to feel our way down the road.” “Cat- eyes” were slitted headlight covers that reduced light to a dim beam on the highway.

Nobody wanted to invite air or ground ambushes — only some trucks had .50-caliber machine guns for defense, he said. The drivers carried only carbines.

The strain on personnel and equipment began to show. Drivers wanted to live up to their growing reputation among combat units and reporters, who sent home news stories about their exploits. They regularly began to ignore speed and weight limits and their own fatigue. The number of one- vehicle accidents climbed. The solution was easy — the Army assigned relief drivers to ride shotgun.

“We hauled anything Gen. Patton needed,” said Rookard, who was drafted into the Army in March 1943 and was discharged in December 1946. “We took supplies all the way to the front line, back and forth, back and forth. Some of the fellows ran into ambushes, but my company, Company C, 514th Quartermaster Regiment, wasn’t. We were lucky, because there was shooting all around us. The Germans had ‘buzz bombs’ (V-1 missiles). They were set to fly a certain amount of miles and (then) drop just like a bomb. We had to watch out for those.

“My worst memories of being in the Red Ball Express were seeing trucks get blown up and being afraid that I might get killed,” said Rookard of Maple Heights, Ohio. “There were dead bodies and dead horses on the highways after bombs dropped. I was scared, but I did my job, hoping for the best. Being young and about 4,000 miles away from home, anybody would be scared.”

Rookard (pictured above), who became a Cleveland city truck driver after the war and retired in 1986, said the only fond memory he has is that of the French people, who treated African Americans nice.

“Some of the white soldiers told the French people that black soldiers had tails and stuff like that,” he said. “But other than that, our company didn’t have too much trouble with segregation and discrimination.”

When the program ended in mid-November 1944, Red Ball Express truckers had delivered 412,193 tons of gas, oil, lubricants, ammunition, food and other essentials. By then, 210,209 African Americans were serving in Europe and 93,292 of them were in the Quartermaster Corps.

There have been a few references to the triumphs of the Red Ball Express truckers. The 1952 film Red Ball Express featured some African-Americans, including Sidney Poitier, although in a supporting role even though the majority of the truckers were African-American. In 1973, CBS aired a situation comedy called Roll Out! about the adventures of a largely African-American trucking company on the Red Ball Express. Following in the footsteps of the iconoclastic Korean War comedy M*A*S*H (1972-1983), Roll Out! used World War II for a commentary on segregated race relations. The show only lasted 12 episodes.

“You never hear anything about us in the media; it makes me bitter that we were never recognized” complains former “Red Baller” James Cranchall.

Now 82, Cranchall, a resident of Philadelphia, was a part of the historic June 1944 D-Day landing and invasion of Nazi-held France along with 120 African Americans of the all-black 427 Quartermaster Truck Battalion.

Below is a video created by the son of a Red Ball Express trucker.