Happy Hump Day POU!

Today’s feature is another incredible story that deserves the attention of a major motion picture studio.

Edward Allen Carter, Jr. (May 26, 1916 – January 30, 1963) was a United States Army Staff Sergeant who received the Medal of Honor for his actions during March 1945 during World War II. He was one of seven African-American soldiers who were awarded the Medal of Honor on January 13, 1997 by President Bill Clinton.

Carter was born in Los Angeles, California in 1916. He was the son of missionaries, with a black American father and an East Indian mother, he grew up in India and then moved to Shanghai, China.

While in Shanghai in 1932, Carter ran away from home and joined the Chinese Nationalist Army fighting against invading Japanese during the Shanghai Incident. He eventually had to leave the Nationalist Army because he was only 15. He eventually made his way to Europe and joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, which was an American volunteer unit supporting the Spanish Loyalists fighting against General Francisco Franco‘s regime during the Spanish Civil War.

Carter had entered the Army on September 26, 1941. As a result of his previous combat experience, he stood out among the other recruits. In less than a year, he had achieved the rank of staff sergeant.

He was member of a unique type of organization — the Seventh Army Infantry Company Number 1 (Provisional), 56th Infantry Regiment Company No. 1, 56th Armored Infantry Batalion, 12th Armored Division near Speyer, Germany.

The provisional companies generally were established during, and in the wake of, the Battle of the Bulge, which took place during the winter of 1944-1945. Black support and combat-support soldiers, and some whites, were allowed to volunteer for combat duty and were given training in small-unit tactics. Formed into provisional units, they were used to augment depleted divisions.

On March 23, 1945, Carter, a 28-year-old infantry staff sergeant, heroically acted when the tank on which he was riding was hit by bazooka fire. Dismounted, Carter led three soldiers across an open field. In the process, two of the men were killed and the other seriously wounded.

Carter continued alone and was wounded five times before being forced to take cover.

He waited patiently, bleeding into the frozen earth for two hours. When the eight-man German patrol stepped into the clear, he opened fire on them, killing six and capturing two. Carter used his prisoners as human shields to make his way back to his company. Fluent in German, he extracted information from his prisoners that helped the Army capture Speyer, Germany. For this he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Carter was refused re-enlistment in Army in 1949 because of unfounded allegations that, as a result of his affiliation with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and a Welcome Home Joe Dinner, he had communist contacts and allegiances. He died of lung cancer on January 30, 1963, in the UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. He was re-buried at Arlinton in 1997.

Following the award of the nation’s highest military honor for combat gallantry in 1997, Carter’s family pressed for the answer to a 50-year-old mystery: Why had the Army barred him from re-enlisting in 1949. When they learned earlier this year that the Army’s bar stemmed from a groundless concern he was a communist, they demanded justice and that his name be cleared. They got their wish Nov. 10 when the Army apologized during ceremonies in the Pentagon’s Hall of Heroes.

“We’re here to apologize to his family for the pain and humiliation he suffered so many years ago at the hands of his Army and government,” Army Vice Chief of Staff Gen. John M. Keane told Carter’s widow, Mildred, and about 30 other family members and friends in 1999. “No words can right the wrong or undo the injustice that was done to Sgt. 1st Class Edward Carter. We must, however, acknowledge the mistake, apologize to his family and continue to honor the memory of this great soldier.”

Carter’s two sons, Edward A. Carter III and William Carter accompanied their mother to accept the apology. Also present was Edward’s wife, Allene, who spearheaded the three-year battle to clear her father-in-law’s name and to set the record straight.

Carter’s Lincoln Brigade service apparently caused Army officials to investigate him secretly and then keep close watch on him throughout his service. The note that triggered the watch intimated only that Carter’s time in Spain might have exposed him to communism. Another note mentioning his ability to speak Chinese was more “evidence.” The Army ignored two of his commanders who recommended the whole matter be dropped as groundless. Despite an extensive investigation, the Army never found any evidence that Carter was a communist, a sympathizer or in any way disloyal.

Keane said recounting Carter’s bravery and determination reveals the depth of the injustice done him after the war.

“We are here today to set the whole record straight, to acknowledge that a man of great personal courage who served his country with honor and dignity was denied the opportunity to re-enlist — without explanation and without the opportunity to defend his good name and preserve his honor,” the general said.

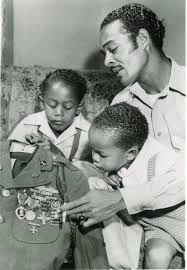

Army Vice Chief of Staff Gen. John Keane presents William Carter, left, and Edward A. Carter III a shadow box filled with the Medal of Honor and other awards and decorations earned by their father, Army Sgt. 1st Class Edward A. Carter Jr. during World War II.

Keane said Carter fell victim to the wave of anti-communist hysteria that engulfed America after the war. Though Carter was honorably discharged on Sept. 21, 1949, his papers noted “not eligible for re-enlistment except upon permission of the adjutant general.”

He spent the rest of his life trying to find out what was behind those 11 words. He died of lung cancer in 1963 at age 47 with his question unanswered.

When the seven African American heroes received Medals of Honor in January 1997, Allene Carter and other family members used the occasion to press for answers. The Army’s secret records came to light, and the Army Board of Correction of Military Records recently determined the Army’s treatment had been unjust. It ordered Carter’s 1949 discharge certificate expunged.

Keane presented Carter’s widow with a new discharge certificate, back-dated to Sept. 21, 1949, that now indicates Sgt. 1st Class Edward A. Carter is fully eligible for re-enlistment. The general also presented the family with three military awards Carter earned but never received — the Good Conduct Medal, Army of Occupation Medal and the American Campaign Medal.

Carter’s picture hangs with Medal of Honor recipients in the Pentagon’s Hall of Heroes.