Happy Hump Day POU!

As with just about every genre of music popular in the United States, it should come as no surprise that the bluegrass music of Appalachia, was created by African Americans.

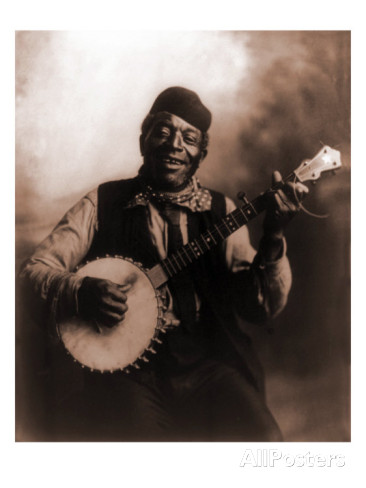

One of the most iconic symbols of Appalachian culture— the banjo— was brought to the region by African-American slaves in the 18th century. Black banjo players were performing in Appalachia as early as 1798, when their presence was documented in Knoxville, Tennessee.

After the Civil War, Black minstrel companies offered real African American music, not pale imitations, eclipsing the white minstrels’ popularity by 1900. African American banjo syncopation helped inspire ragtime, a combination of folk, popular, and art music born in the Black Midwest that became internationally popular in the 1890s and 1900s. Scott Joplin, the great ragtime composer, dedicated compositions to Black banjoists. More ragtime banjo records than piano records appeared in the early 1900s. As banjo playing became a vital part of turn of the century popular music, Black Banjoists like Horace Weston, the Bohee Brothers, Hosea Eason, and James Bland became international stars. Black banjo playing probably reached its height before World War I. Black banjoists swung old time dances and starred in shows from London to Broadway.

Middle class African Americans formed banjo, mandolin, and guitar clubs. The most prominent, Washington’s Aeolians, played for thousands while Black newspapers across the country covered their concerts as society news. Black bandleader James Reese Europe, New York’s foremost bandleader who bridged ragtime and jazz, led a band that featured six banjoists among only ten musicians and formed concert orchestras with scores of banjos. New banjos without drone strings and played with flat picks arose in the 20th Century: tenor banjos, tuned like violas, six-string guitar banjos, mandolin banjos, and plectrum banjos, modeled on the five string banjo without the fifth string. The jazz banjoists that played them included musicians like Elmer Snowden, Zach White, Johnny St. Cyr, Noble Sissle, and Freddie Green, who became major jazz guitarists, band leaders, and composers.

Across the 20th century, the banjo declined. Musicians, white and Black, abandoned the banjo as the old time dances died out. Though Memphis five-string banjoist Gus Cannon made thirty-three blues and rag records from 1927 to 1930, pianos and steel stringed guitars dominated the blues. In jazz the new large arch top and, later, electric guitars replaced banjos. Even in country music, the banjo became chiefly a prop for hayseed comedians until Earl Scruggs changed everything in 1945. Yet, African American traditional banjoists survived even if their music was no longer popular. Folklorists and banjo enthusiasts found and documented surviving Black banjoists like Dink Roberts, Nate and Odell Thompson, Rufus Kasey, Elizabeth Cotton, Lewis Hairston, and Etta Baker. Scholars like Dena Epstein and Cece Conway, reaffirmed the African ancestry, Caribbean origins, and Black American history of the banjo. Starting with 1960s folk blues performers Taj Mahal and Otis Taylor, a new generation revived Black banjo playing.

The 2005 Black Banjo Gathering in Boone, North Carolina brought this revival to a new stage. Featuring scholars and players of West African music; Black banjoists like Jazz banjoist Don Vappie; the Ebony Hillbillies, New York’s Black string band; the young Black musicians who later formed the Grammy-winning Carolina Chocolate Drops; banjo historians like Robert Winans and Cece Conway; and leading banjoists like Mike Seeger and Bela Fleck, the gathering celebrated both African American banjo heritage and the Black banjo revival.

African American musicians at the 2010 Black Banjo Reunion at Appalachian State University Boone, North Carolina, 27 March 2010.

The banjo is believed to have been popularized among white musicians through blackface minstrelsy, which was performed in the Appalachian region throughout the 19th century. African-American blues, which spread through the region in the early https://bea-skincare.com/wp/buy-accutane-online/ 20th century, brought harmonic (such as the third and seventh blue notes and sliding tones) and verbal dexterity to Appalachian music, and many early Appalachian musicians, such as Dock Boggs and Hobart Smith, recalled being greatly influenced by watching black musicians perform.

The Birth of Bluegrass

Bluegrass grew in interactions among black musicians who employed banjo and African tonalities and white ones who played fiddle tunes and sang ballads and hymns brought from England, Ireland and Scotland.

The musicians who in 1945 created the style now known as bluegrass freely acknowledged their debt to black music. Bill Monroe, the Kentuckian and bluegrass founder who once broadcast on the powerful Raleigh radio station WPTF-AM, always cited black fiddler and guitarist Arnold Shultz as one of his prime influences.

The Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, two foundational acts of country and bluegrass, drew heavily on blues and other black styles, sometimes putting their names on songs or lyrics that had long circulated informally. Songs such as “John Henry” and “Sittin’ on Top of the World” were popular across the board.

The genre-crossing blue notes in those songs also emerged in vocal and instrumental styles of bluegrass founders such as Monroe, Scruggs and the Stanley Brothers.

After bluegrass gained commercial popularity in the late 1940s and ’50s, its key performers toured constantly, something that was more difficult for black performers. Black string band musicians such as Mebane’s Odell and Joe Thompson became less visible.

But in the 21st century, Joe Thompson made an indelible mark on the young black musicians who started the Chocolate Drops.

“When you have the opportunity to meet Joe and sit with him, this music becomes less of a distant thing,” Jenkins said.

Mainstream bluegrassers continued to draw inspiration from more contemporary blues, gospel, R&B even rock ’n’ roll, with Grand Ole Opry stars Jim & Jesse McReynolds recording an entire album of Chuck Berry songs and the award-winning Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver recreating tunes by Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers.

But many bluegrass festivals and clubs tended to be segregated in fact if not by law, and the music took on associations with the old South, said Allen Farmelo, a New York scholar and musician.

“What I found was that bluegrass festivals were a scenario in which nobody I know who was black would have felt comfortable attending,” he said, adding that exclusionary signs were more cultural than official.

“Did I see the Confederate flag hanging from motor homes?” Farmelo said. “Absolutely.”

Scholars and musicians such as Lexington’s Bob Carlin have put years into studying the West African origins of the banjo and its links to Southern string music.

IBMA artist Fleck, probably the best-known player to perform many different styles on the banjo, made the documentary “Throw Down Your Heart” to illustrate the links between the instrument that can play “Rocky Top” or “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” and the similar one still played in Africa.

The Carolina Chocolate Drops perform “Genuine Negro Jig” live at Mass MoCA 5/29/10

And of course the roots of Square Dancing are inspired from where else but….Africa

Square dance at Howard University, following a reception for Mary McLeod Bethune, 1949

Researcher and Scholar Phil Jamison discusses his research into the origins of American square dance in the south, and describes the key role that African-American musicians played . There are the well-known musical elements—the role of the banjo, for example—and Phil also points out that the first callers were African-American. Even some distinctive square dance features such as Birdie in the Cage may have African roots.