Happy Hump Day POU!

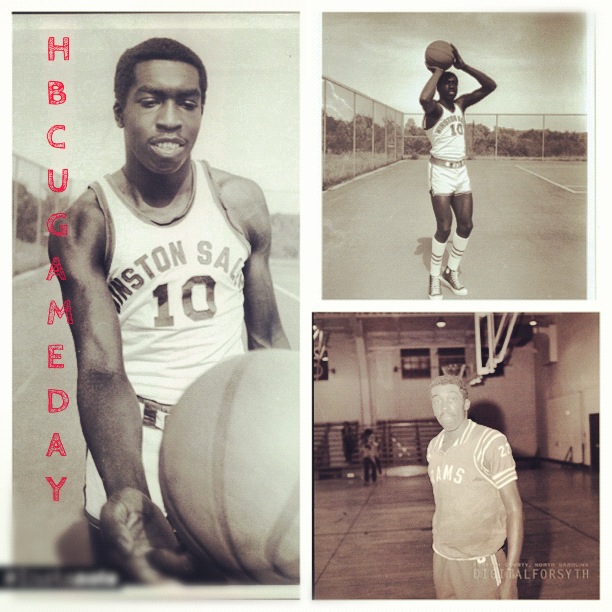

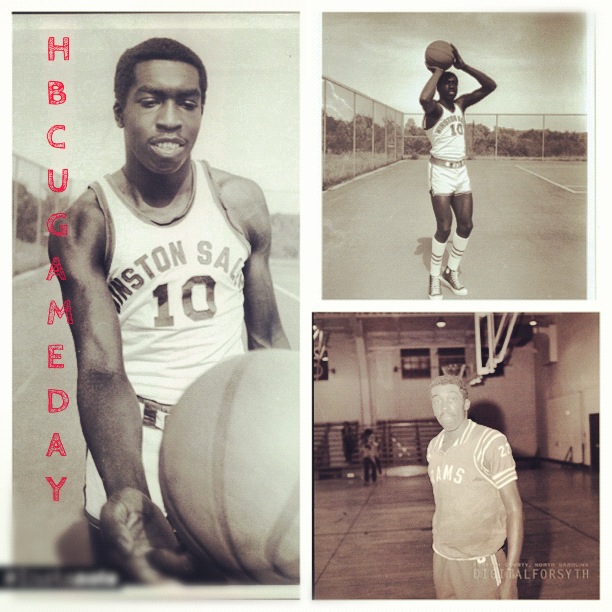

Today we honor the legendary Earl “The Pearl” Monroe and his impact on HBCU basketball and integration.

Vernon Earl Monroe was known for his flamboyant dribbling, passing, and play-making. He was nicknamed both “Earl the Pearl” and “Black Jesus”.

Born in Philadelphia, PA, Monroe was a playground legend from an early age. His high school teammates at John Bartram High School called him “Thomas Edison” because of the many moves he invented.

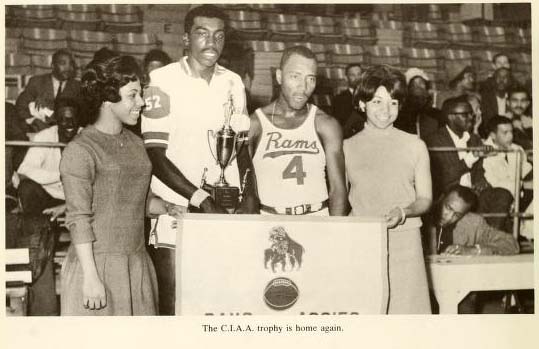

Monroe rose to prominence at a national level while playing basketball at then Winston Salem State College in North Carolina. Under Hall of Fame coach Clarence “Big House” Gaines, Monroe averaged 7.1 points his freshman year, 23.2 points as a sophomore, 29.8 points as a junior and an amazing 41.5 points his senior year. In 1967, he earned NCAA College Division Player of the Year honors and led the Rams to the NCAA College Division Championship.

The Pearl’s impact on the game of basketball is legendary. Known as the father of the spin move, Earl captured the imagination of the nation’s basketball fans in his rookie year with the Baltimore Bullets. However, before gaining national acclaim in the NBA, he captured the hearts of many southerners, both black and white, with his defining game and brilliant play in his four years at Winston-Salem State College (now Winston Salem State University). In the 1966-67 season Earl led his team to a national championship in the NCAA’s College Division averaging 41.5 points per game. Ask many old timers in North Carolina and Earl Monroe’s greatest contribution as a basketball player was helping to break down racial barriers in North Carolina.

Ralph Wiley’s brilliant article, “Seeing the Game Through Pearl Vision,” captures the essence of Earl’s game and impact:

“Earl Monroe had better than fame. He had genius. He had rep. And he had them at all meaningful levels of the game. He was a genius at the playground level, a genius at the collegiate level, a genius at the NBA level, a genius at the upper echelon All-Star NBA level, and a genius at the NBA championship level. He is all-time. He is legend. Pearl.”

“What happened then? Well … Earl the Pearl Monroe helped integration even before Martin Luther King did — anyway, to tell you the truth, at just about the same time. Later, as a pro, he’d read King’s speeches before he played and let that inspire him. Back then, the legend went from the playgrounds of Philly moved to Tobacco Road, where tales were told about a young man with the ball on a string who could move your soul with his inspired improv.”

“The story spread underground, like wildfire, across Hoop Nation. It was said he could not be described. He could only be seen, and even then unseen. He required faith — the evidence of things not seen. His improv was a revelation, as much science as art. You could no more describe Pearl’s game than you can describe color, music or literature.”

“All you can say is there’s a right way to play, and a not-right way to play, and an inspired way. Earl originated the spin move, yes, and on first sighting it moved the soul like water turning to wine. But, see, the thing is … Earl always spun toward the basket.”

From the autobiography, ‘Becoming Earl the Pearl”:

MY SENIOR YEAR STARTED OUT with us playing some important scrimmages against the Wake Forest University basketball team that had been arranged by the Demon Deacons’ head coach Jack McCloskey and his assistant coach, Billy Packer. Coach McCloskey had coached at the University of Pennsylvania when I was going to high school in Philadelphia, so he knew about me. Billy Packer had played at Wake Forest and had gone back there as an assistant coach (later, he would become a famous basketball color analyst for CBS), and he loved Cleo Hill as a basketball player. Anyway, Billy set up these practice sessions and our team and Wake Forest had about six of them at their gym. I remember when we got there, Coach McCloskey, who was a friend of Coach Gaines, saw that our ankles weren’t taped and he told Coach Gaines they weren’t going to let us play until he had us tape our ankles, which he did.

Now, we weren’t used to playing with our ankles taped–it was a cost factor at Winston-Salem because the administration didn’t have the money–and it almost felt like we were wearing casts. It was that stiff at first. So in that first scrimmage they beat us because we couldn’t hardly move. But then we got used to our ankles being taped and we beat them five straight games. I remember me and their star player, Paul Long, having some spirited sessions. I also remember Coach Packer asking me to show the Wake Forest players my spin move. I tried, but the move was too quick and new for them–they were all white guys and weren’t used to trying nontraditional basketball moves–to absorb. So he asked me to slow it down some so they could get it and I tried to do that, but my move was too intuitive, improvised, and spontaneous for them to wrap their heads around it.

After I realized I couldn’t explain it to them verbally–it’s hard to explain improvisation to someone who has never had to do it–I just stopped. One of my favorite sayings around that time was that whoever was guarding me couldn’t ever figure out what I was going to do with the ball because I didn’t know myself until I did it. So teaching them the spin move was out of the question. They had to feel their way through to learning and doing it and maybe, you know, their culture got in the way a bit. Perhaps the way they had been brought up in the game prevented them from being able to execute an improvised move. I don’t know, but it’s something to think about when comparing black basketball culture to its white counterpart. Still, those early scrimmages pulled our team together and got us off and running. Knowing that we could beat a major college team like Wake Forest gave our squad a lot of confidence going into the season. It also injected more purpose into my game.

I remember playing in the Chicago Invitational Tournament in late December of my senior year. I had been scoring a lot of points during the first games of the season, and a Chicago sportswriter said that I wouldn’t get 50 points when I came out there to play. So in the first game of the tournament I just stopped shooting with two or three minutes to go, after I had already scored 48 or 49 points and we had established a manageable lead. I just wouldn’t shoot anymore because I didn’t want to get 50, just to let them know I was in control. Later, in the championship game against Wilberforce University, we were down at the half and I had to shoot in order for us to win 101-100. I got 50 points on the nose, okay? Because I could get 50 points anytime I wanted to. So I’m standing with my guys when they announce the MVP award, which I just knew would go to me. But they gave the trophy to Melvin Clark, a guy on the team we had just beat. He was a black, classic-style player, a forward I think, and he scored maybe 30 points in the championship game. I scored 50, and we won! Their excuse was that they had voted on the award during halftime. Everybody was shocked, but the guy who won went up and picked up his trophy like he deserved it and didn’t even acknowledge me. I never saw or heard from him again after that. I don’t know what happened to him and I’d even forgotten his name until I looked it up for this book.

One of the most gratifying memories of my senior year was when we had to move our games from our home gym to the Winston-Salem Memorial Coliseum–the same place Wake Forest played–because the crowds were getting so big. We were beating everybody and I was scoring so many points that we were packing them in like sardines, with every seat sold for every home game. Black and white people, young and old. People were being turned away, couldn’t even buy seats, or find tickets anywhere. Even when we went on the road to play it was like this, with all of our games having to be moved from the school gym to the largest facility in any given town. All our games were sold out. Everywhere. It was something. Blew my mind.