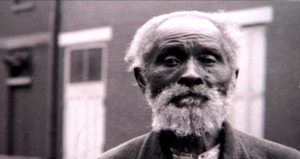

Fountain Hughes (1848 — 1957) was born a slave in Charlottesville, Virginia in the United States and freed in 1865 after the American Civil War. He worked as a laborer for most of his life, moving in 1881 from Virginia to Baltimore, Maryland. He was interviewed in June 1949 about his life by the Library of Congress as part of the Federal Writers’ Project of former slaves’ oral histories. The recorded interview is online through the Library of Congress and the World Digital Library.

Fountain was a grandson of Wormley Hughes and Ursula Granger, and great-great-grandson of Betty Hemings, the slave matriarch at Monticello. Wormley Hughes and his family were owned by President Thomas Jefferson at the time of his death.

After Thomas Jefferson’s death, Wormley Hughes (who had worked as a gardener) was among the “elite” slaves who were “given their time.” This was an informal freedom, a non-legally binding release from the demands of enslavement without legal release, awarded usually to respective members of the slave-holder’s own enslaved descendants and, at times, to other slaves deemed to have shown especially dedicated service. Despite this, Hughes’ wife Ursula and all their children were sold in 1827, along with all but five slaves from Monticello, to settle outstanding debts of the estate. Hughes appealed to Jefferson’s grandson to try to keep his family together; Thomas Jefferson Randolph purchased Hughes’ wife and his three sons and took them with Wormley to his plantation of Edgehill. Three daughters of Hughes were sold ultimately to people in Missouri and Mississippi; others stayed closer.

Fountain Hughes was born a slave near Charlottesville, Virginia and, with his mother, owned by “B”. His father, also owned by B, was killed in the American Civil War. As a slave child, Hughes was sometimes sent as a messenger to another house and would carry a pass to show he was allowed to travel. He said none of the slave boys were given shoes until they were about 12 or 13; they always went barefoot. He described their sleeping on pallets on the floor of their quarters; they did not have beds until after freedom. After being freed, he worked for ten dollars a month.

Hughes moved to Baltimore in 1881. For a time, he worked as a manure hauler for a man named Reed. A recorded interview was conducted with him on June 11, 1949, by Hermond Norwood (a Library of Congress engineer at the time). It has been included with other interviews done by the Federal Writers’ Project during the Great Depression. The recording is available online at the World Digital Library, as well as through the Library of Congress.

Hughes noted changes from how people lived in the early 20th century. He said that in the 1940’s, many people bought things on credit instead of saving up for them. He said, “If I’ve wanted anything, I’d wait until I got the money and I paid for it cash.” He also said that, when he was growing up in the 19th century, young people could not spend money until they were 21 because they would be suspected of stealing the money. Children never had money to spend on their own. When asked which life he preferred, Hughes said he would rather be dead than a slave again. Hughes died in 1957.