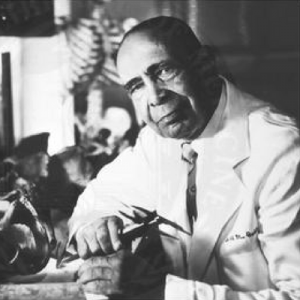

William Montague Cobb’s career from its inception paralleled nearly the entire history of professional physical anthropology in the United States. As a leading activist scholar in the Afro-American community and the only black physical anthropologist Ph.D. before the Korean War, Cobb was the sole representative of Afro-American perspectives in physical anthropology for many years.

During his last tenure at Howard University Medical School, the school was in a state of transition. The first appointed black president felt that the black students in the medical school were not getting the best education that they could receive from the mostly all white faculty. So he began to recruit black faculty, which was very hard to do during this time period.

To combat this, the dean of the school picked the top students to send to graduate school. Dr. Cobb was one of three chosen and he was sent to Western Reserve Universityto receive training in gross anatomy and physical anthropology. Dr. Cobb began his training under T. Wingate Todd, one of the leading anthropologists during the time. Todd believed that there were no racial differences between whites and blacks. He studied the brains of children and came to the conclusion that there were no biological differences in the development of the brain, but that physical conditions, and the toll of life produced slower growth in some children.

To combat this, the dean of the school picked the top students to send to graduate school. Dr. Cobb was one of three chosen and he was sent to Western Reserve Universityto receive training in gross anatomy and physical anthropology. Dr. Cobb began his training under T. Wingate Todd, one of the leading anthropologists during the time. Todd believed that there were no racial differences between whites and blacks. He studied the brains of children and came to the conclusion that there were no biological differences in the development of the brain, but that physical conditions, and the toll of life produced slower growth in some children.

This way of thinking would shape Dr. Cobb, and influence his work in later years. Upon his completion of graduate school he returned to Howard University eager to start work in his own laboratory. Dr. Cobb went on to publish multiple journals and dissertations. In his work he sought out to highlight African Americans in a positive light considering their circumstances instead of highlight the negative. Dr. Cobb began attending meetings of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. At these meeting anthropologists could come together and have think tanks. From these meetings Dr. Cobb developed life long friends but also experienced racism. While most of his colleagues came to accept him they did not want him to have powerful positions that could end with him having power over them.

Growing up Dr. Cobb was athletically gifted; training himself in boxing and also track and cross-country. This predisposition to sports drew him to study the relationship between race and athletics. The 1936 Olympics that took place in Berlin, Germany caused much uproar when Jesse Owens, a black man, won four gold medals. Many came to believe that blacks had certain biological characteristics that would make them better at sports than their white counterparts. Dr. Cobb disagreed. He argued that there was not sufficient evidence to support this claim.

He measured Jesse Owens’ legs and other body parts and determined that statistically he had body parts on average measure with both whites and blacks. Cobb came to the conclusion that Owens’ training is what caused him to perform well and not his biological make up. Cobb published his findings in Race and Runners. Dr. Cobb utilized all of his experiences in life, and different mentors and colleagues to develop his own way of thinking.

Dr. Cobb’s impact can be found not only in the scientific community but also in the progress African Americans have made since the 1900s. Cobb made an impact everywhere he went. From 1932 to 1969 Cobb worked at Howard University Medical school and the impact of his work can be seen today on campus. During his tenure at Howard University, Dr. Cobb took on many roles in organizations on Howard University campus and in the surrounding D.C community. He served as a member of the of the board of directors of the Friends of the National Zoo, chairman of the D.C. Public Health Advisory Council and the D.C. Citizens Advisory Committee to Reduce Litter , secretary of the Anatomical Board of the District of Columbia and on the executive committee of the White House Conference on Health.

Located on the second floor of Fredrick Douglass hall on Howard University’s campus, the W. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory houses the Cobb Human Skeleton Collection. The collection contains the records of about 987 people and more than 700 documented skeletons. What makes this collection different from any other in the world is that it contains the skeletons of African Americans in the D.C area. Currently the lab is working with remains from the New York African Burial Ground under the director of the lab, Dr. Fatimah Jackson. Dr. Cobb’s lab is currently carrying out his mission of training the next generation of physical anthropologists.

Outside of Howard University, Dr. Cobb had an impact that changed the face of medicine. In November of 1929, Aleˇs Hrdlicka founded the American Association of Physical Anthropologists with a goal to prove that White Europeans were genetically superior to Blacks and other minority races. Hrdliˇcka, however, faced opposition in his research from several scientists. Franz Boas, the father of American anthropology, and T. Wingate Todd criticized the idea that the differences in the genetic makeup of the different races made one race superior to the other.

When Cobb entered the field of physical anthropology, the debate over racial determinism was at an all time high. Some physical anthropologists believed that African Americans were naturally inferior to Whites due to their genetic makeup while others aimed to disprove scientific racism. When Cobb first opened his lab he made it a point to note that the purpose of his lab was to prove that African Americans are not physically or mentally inferior simply because of their race. In order to prove that African Americans were not inferior to Whites based on race, Cobb had to do something no other scientist had dared to do before, Cobb had to create a collection of African American skeletons and records.

(Read more at Cobb Research Lab)