Happy Hump Day POU!

We continue our series on Black Athletes and their involvement in social and political protests. Today we look back on The Orangeburg Massacre.

On a February night in 1968, a linebacker on the South Carolina State football team named Robert Lee Davis went with three or four teammates to a bowling alley just off the black college’s campus in Orangeburg. Theirs was not an act of recreation but of political protest.

As expected, the alley’s owner turned them away because only whites were admitted. Then the local police arrived to arrest the players for disturbing the peace. When other students nearby began to object, the officers drew their nightsticks and the beatings began.

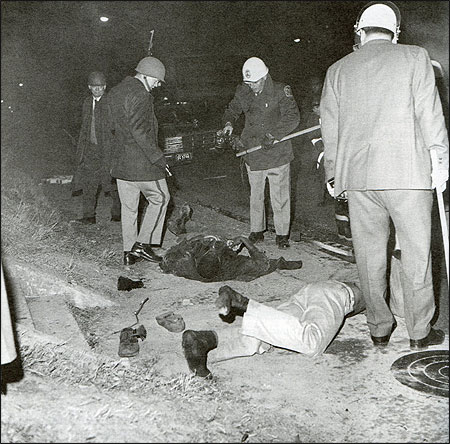

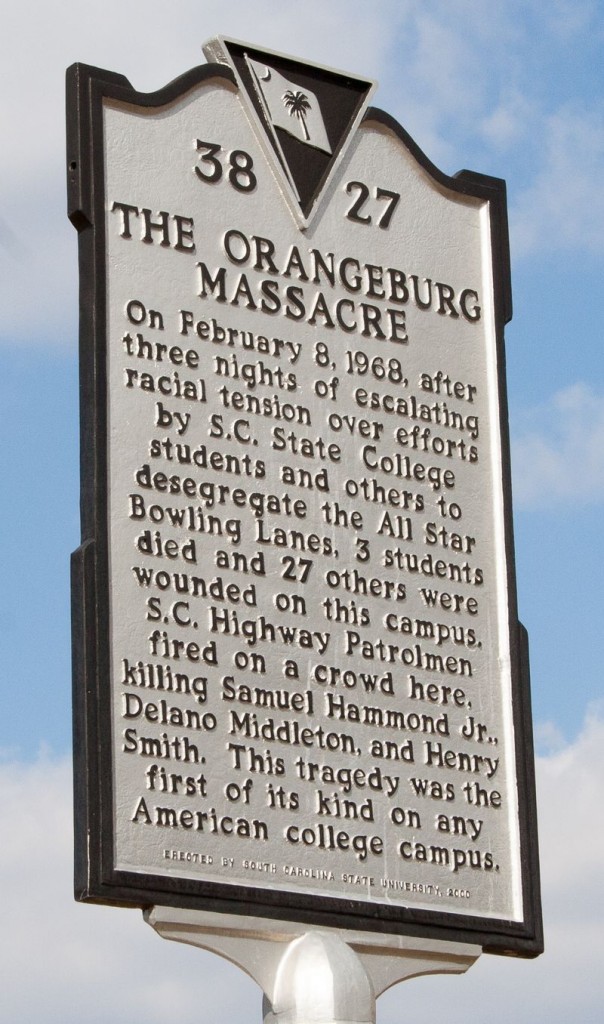

Two nights later, on Feb. 8, 1968, Davis and a larger group of football players joined their fellow students in building a bonfire near the campus entrance in a demonstration against the police assault. This time, an all-white force of state troopers responded. By the time the lawmen were done firing, 3 students lay dead and 27 had been wounded.

Those killed were 18-year-old SC State students Henry R. Smith and Samuel Hammond Jr., 17-year-old high school student Delano B. Middleton

The Orangeburg Massacre, as the event came to be called, has grown over time into a landmark in civil rights history. More specifically, it stands as a tragically valiant episode in the history of political activism by black athletes, specifically the football players and the coach of South Carolina State.

One football player, Samuel Hammond, died in the hail of fire from the state troopers. Several others were injured, Davis severely enough to be temporarily paralyzed. In the aftermath of the shooting, defensive back Willis Ham and three other student-athletes made a protest run 42 miles from Orangeburg to the state capital of Columbia.

The players’ protests at South Carolina State predated more famous examples of black athletic activism like the movement to boycott the 1968 Summer Olympics and the bowed-head, clenched-fist salutes from John Carlos and Tommie Smith on the medal stand during the Mexico City Games that year.

Black colleges on the whole were deeply involved in the civil rights movement, and though some athletes took up the cause, they tended to be the exception rather than the rule. Jesse Jackson was both a quarterback and a protest leader at North Carolina A&T. Willie Galimore, a star running back for Florida A&M and then the Chicago Bears, helped to integrate the Ponce de Leon Hotel in St. Augustine, Fla., a focus of civil rights protests. A defensive lineman for Grambling, Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick, helped found and lead the Louisiana group Deacons for Defense and Justice, which guarded civil rights volunteers.

Still, on Friday’s 45th anniversary of the Orangeburg Massacre, the movement at South Carolina State remains notable for the depth of commitment by athletes and for the bloody price the players paid.

“There was no play as vicious as that play,” one of the wounded players, Harold Riley, recalled in an interview conducted for the Orangeburg Massacre Oral History Project. “To see people crying and dying, you know, that kind of stuff. You don’t die on the football field. You miss a play, and you get up and run another one. This play here was a play you never forget.”

The story of the South Carolina State football team and the Orangeburg Massacre began several years earlier, in a certain sense, with the arrival of two men. One was Oree Banks, who became coach in 1965. The other was Cleveland Sellers, the national program director for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, who started mobilizing students on the campus in early 1967.

Many presidents of black colleges — as well as the coaches who worked for them — felt an excruciating tension between the white governors and legislatures that controlled their jobs and the righteously restive students who had grown up amid Brown v. Board of Education, the Montgomery bus boycott and the March on Washington.

In both age and temperament, Banks bridged the groups. Though born in Mississippi, he had experienced integration while serving in the Army and earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Kansas State. In the same year when he took the South Carolina State job, Banks joined the N.A.A.C.P., a daring move at a time when some Southern states had outlawed membership in the group and the organization was routinely likened to the Communist Party.

In Orangeburg, Banks quickly set about reversing South Carolina State’s football fortunes, going 22-4 in his first three seasons and developing such future pros as R. C. Gamble and James Johnson, known as Diesel. Just as significantly, he offered tacit approval when his players were drawn into the campus protest movement. Doing so put Banks at risk of being fired.

“It wasn’t easy for me,” Banks said in a 2011 interview. “Probably some of the coaches back then would’ve put the emphasis on players not being involved. That wasn’t what I was all about. I took an attitude that this is a part of the change in our country. This was a change that people needed to be concerned about.”

As for Sellers, when he started assisting a student protest group called The Cause, he deliberately sought out football players. “The football team had an organization of their own, they had leaders, they had influence over the coeds,” he said in an interview two years ago. “It was an important ingredient to have them.”

The South Carolina State campus and Orangeburg had seen demonstrations against segregation in 1957, 1960 and 1963, the last quashed by local police wielding fire hoses. Sellers had also surmised correctly that the football players had experienced inequality through the sport they loved: second-rate facilities and equipment, road trips without any stops at restaurants or to use public restrooms.

Some of the players from Charleston, like Ham, had already been exposed to civil rights activity. Others, like quarterback Johnny Jones, discovered the left-wing counterculture while working summer jobs in Northern factories.

All of the various influences, added together, overcame the prevailing concern for many athletes at black colleges. Their scholarships were often the only way they could afford to pursue a college degree. Being stripped of a scholarship, and conceivably being kicked out of school, meant not only losing that dream but becoming instantly eligible for the Vietnam War draft.

When the South Carolina State players wavered and went to Banks for advice, he did not tell them what to do, at least not overtly. What he did say, Jones recalled, was: “You’re making history. Don’t be on the wrong side of it.”

The pace of that history at South Carolina State quickened through 1967. The university’s president, Benner C. Turner, was already under criticism from The Cause for his timidity on civil rights — not allowing an N.A.A.C.P. chapter on campus, erecting a fence to prevent large demonstrations — when he dismissed two math instructors, both of them young white men from the North, who had been persistently raising the issue of inadequate funds and facilities at the college.

In response, several hundred students, including many football players, picketed on the front lawn of Turner’s residence. He expelled three of the protest leaders, which resulted in an even larger demonstration, involving roughly a third of the college’s 1,500 students, and subsequently a two-week boycott of classes honored by 90 percent of the student body.

Turner was dismissed after the spring term for having lost control of the campus. The student movement, emboldened by its success, picked up the decade-long campaign against segregation in Orangeburg, focusing on a downtown bowling alley.

The state police were dispatching agents to investigate Sellers and his followers. But the football players, already politicized, were not backing down. “There’s an expression,” Ham recalled decades later of the mood at the time, “that it’s better to ask forgiveness than to ask permission.”

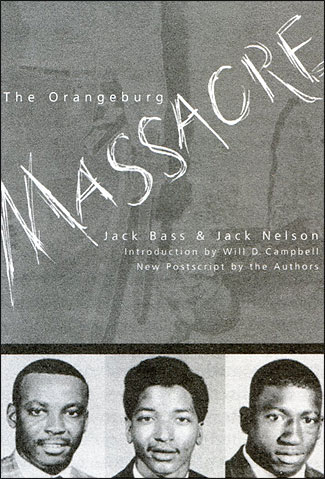

The stage was set for the football players’ visit to the bowling alley Feb. 6 and for the state troopers’ armed reply Feb. 8. Jack Bass, the co-author with Jack Nelson of the definitive history of the episode, “The Orangeburg Massacre,” wrote of that night’s events:

“After two days of escalating tension, a fire truck was called to douse a bonfire lit by students on a street in front of the campus. State troopers — all of them white, with little training in crowd control — moved to protect the firefighters. As more than 100 students retreated to the campus interior, a tossed banister rail struck one trooper in the face. He fell to the ground bleeding. Five minutes later, almost 70 law enforcement officers lined the edge of the campus. They were armed with carbines, pistols and riot guns … loaded with lethal buckshot.”

Soon after the firing started on fleeing students, Robert Lee Davis found himself laying on the ground next to his teammate, Samuel Hammond, both of them bleeding. “He said, ‘Do you think I’m going to live?’ ” Davis recounted in an oral history. “I said, ‘Sam, you are going to be all right, buddy.’ And the next time I looked over, he was dead. I had to put my hand over his eyes.”

In the aftermath, nine state troopers were rapidly acquitted of charges in the shootings. Only Sellers of the S.N.C.C. was convicted of a crime. He spent seven months in prison for “inciting a riot.”

It took decades for the wrongs to be acknowledged. Sellers was pardoned in 1993, and in 2003, Mark Sanford, South Carolina’s governor at the time, issued a formal apology for the shootings. Yet the specific role of black athletes has been largely subsumed in the larger story.

Sellers, now the president of Voorhees College in South Carolina, is one who does remember it. “You could talk to the football players about the struggle and they could relate it to sports,” he said. “How do you develop your manhood? They had the idea to be competitive and to try to win.”