Today’s entry was first posted April 28, 2014 and one in which we’re all familiar.

On a sunny Sunday afternoon in early June 1967, several hundred Clevelanders crowded outside the offices of the Negro Industrial Economic union in lower University Circle. None of those gathered, including a collection of the top black athletes of that time, realized the significance of what would happen in that building on this day.

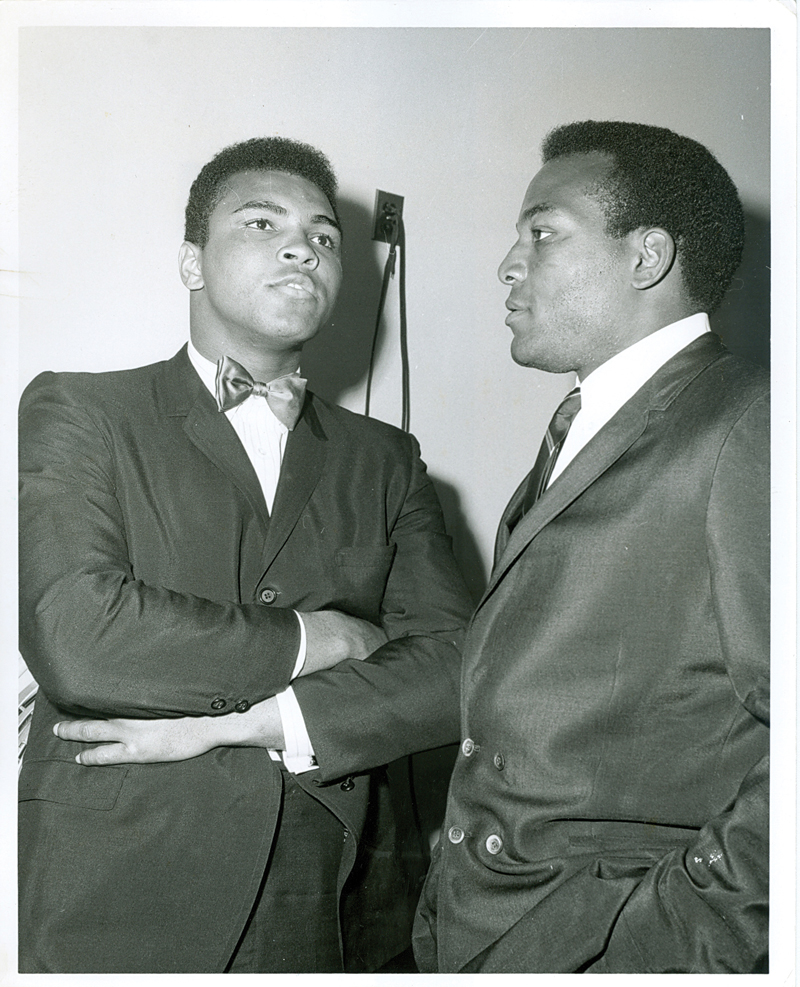

Muhammad Ali, the most polarizing figure in the country, was inside being grilled by the likes of Bill Russell, Jim Brown and Lew Alcindor, who would later change his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

The reason for the meeting? They wanted to know just how strong Ali stood behind his convictions as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. The questions flew fast and furious. Ali’s answers would determine whether Brown and the other athletes would throw their support behind the heavyweight champion, who would have his title stripped from him later in the month for his refusal to enter the military.

The core of the summit was the NIEU, later named the Black Economic Union (BEU).

The organization was co-developed by Brown in 1966, a year after he retired from the NFL to become a full-time actor. The BEU served various communities across the country, mostly in economic development. The BEU also supported education and other social issues within the black community.

The BEU and this meeting with Ali stemmed from Brown’s social consciousness. For the meeting with Ali, Brown brought together other socially conscious black athletes of the time. Besides Russell, Alcindor and Davis, there was Bobby Mitchell (Washington Redskins), Sid Williams (Browns), Jim Shorter (Redskins), Walter Beach (Browns), John Wooten (Browns), Curtis McClinton (Kansas City Chiefs) and attorney Carl Stokes.

“The principal for this meeting of course was Ali,” McClinton said. “The principal of leadership for us was Jim Brown. Jim’s championship leadership filtered to all of us.”

In many ways, Cleveland was also the epicenter of black political and social progress. In November of ’67, Stokes became the first black mayor of a major U.S. city when he was elected in Cleveland. The city became a destination for thousands of blacks who migrated from the South because of job opportunities. When it came to sports, the Browns were popular in the black community, mostly because of their history with black players, such as Marion Motley, Bill Willis and Brown.

“Black people were coming to Cleveland from all over the country to see what we were doing here politically and economically, because no other city was doing it like we were,” said former BEU treasurer Arnold Pinkney, a longtime entrepreneur and political activist.

“Cleveland was a hotbed for black power, energy and Black Nationalism at this time,” said Leonard N. Moore, University of Texas professor and author of the book, “Carl B. Stokes and the Rise of Black Political Power.”

“In so many ways, it was fitting that the meeting happened on the East Side of Cleveland,” he said.

A little over a month before the Cleveland gathering, Ali refused to step forward for induction into the U.S. Army in Houston. That set off a firestorm of criticism of the champ. Ali was also a member of the Nation of Islam, broadly seen as an anti-white cult, even in some circles within the black community.

Harry Edwards, professor emeritus of sociology at the University of California-Berkeley, said there was so much consternation concerning the war and Ali that the fighter became symbolic of almost every rift in society.

“He was already regarded as a loud-mouth Negro while he was Cassius Clay,” said Edwards, referring to Ali’s birth name before his conversion to Islam. “When he joined the Nation of Islam, that exacerbated it even more.”

Ali’s stance helped ignite the rising level of anti-war sentiment.

“The anti-war movement really hit the headlines when Ali refused induction and made his statement about not having any quarrel with the Viet Cong,” Edwards said. “And then to refuse to comply with the draft, that lined up all of those people who were on one side or the other of the Vietnam War.”

In 1967, Brown was in his second year of retirement after leaving the sport as the NFL’s all-time leading rusher. His post-NFL career was spent as an actor, but Brown never lost his zeal as a social activist. When Brown helped form the BEU, the organization established offices in Los Angeles, Kansas City, Philadelphia, New York, Washington and Cleveland. His former teammate, John Wooten, became the executive director of the Cleveland office. Everyone in the meeting with Ali, with the exception of Russell, was a BEU member.

Ohio State graduate student Robert Bennett III, who will complete his dissertation thesis on the BEU later this year, said supporting Ali was not out of the ordinary for the BEU.

“Oftentimes when you look at the history of black athletes, it often looks at their achievements on the field,” Bennett said. “And it’s rare for someone to look at their social or political activism off the field. The athletes involved with the BEU were about defending and supporting issues that supported the black community.”

Shortly after Ali’s refusal to join the military on grounds of being a conscientious objector, Brown received a telephone call from Ali’s manager, Herbert Muhammad. Several boxing governing bodies had already suspended or threatened to suspend Ali’s boxing license. Brown said Herbert wanted him to help convince Ali to reconsider because of the potential loss of income, and because of the anticipated backlash.

Herbert Muhammad was torn because of his religious faith, but he was also in the business of helping Ali make money.

“Herbert wanting Ali to go into the service was a shocker,” Brown said. “I thought the Nation of Islam would never look at it that way. But Herbert figured the Army would give Ali special consideration so he would be able to continue his career. But he couldn’t talk to Ali about that, so he reached out to me and I had the dilemma of finding a way to give Ali the opportunity to express his views without any influence. I never told Ali about my conversation with Herbert. I never told anyone, really.”

There was another backdrop to the meeting. Bob Arum and Brown were partners in Main Bout, Arum’s company that promoted Ali’s fights. Convincing Ali to go into the military would provide economic opportunities for the athletes in the summit.

“The idea was that these guys would become the chief closed-circuit exhibitors for Ali’s fights all over the United States,” Arum said. “Each of them would get a particular region and they would make a nice chunk of change every time Ali fought.”

Subsequently, Brown reached out to Wooten and asked him to contact some of the top black athletes in the country to attend a meeting in Cleveland with Ali.

“Herbert wanted me to talk with Ali, but I felt with Ali taking the position he was taking, and with him losing the crown, and with the government coming at him with everything they had, that we as a body of prominent athletes could get the truth and stand behind Ali and give him the necessary support,” Brown said.

The athletes’ response did not surprise Wooten.

“After I called all of the guys and explained what we were meeting about, they didn’t ask who’s going to pay for this or that, they just asked where and what time,” Wooten said.

Alcindor, who had just finished his sophomore year at UCLA, didn’t hesitate to make the trip.

“Muhammad Ali was one of my heroes,” said Abdul-Jabbar, who was active in the BEU office in Los Angeles. “He was in trouble and he was someone I wanted to help because he made me feel good about being an African-American. I had the opportunity to see him do his thing [as an athlete and someone with a social conscience], and when he needed help, it just felt right to lend some support.”

More importantly, the meeting wasn’t just for Ali.

“Our assembling there was about Ali defining himself, because that definition was a part of us,” McClinton said.

The athletes at the summit were not going to give Ali blind support. Many needed answers to exactly why Ali claimed to be a conscientious objector. There was some confusion regarding Ali’s motives. Three years earlier, Ali failed the Armed Forces qualifying test due to sub-par writing and spelling skills. In early 1966, the tests were revised and Ali was reclassified as 1A, making him eligible for the draft. Initially, Ali said he didn’t understand the change and there was no reference to religion or being a conscientious objector. Many wondered if he was only upset because of the interruption to his boxing career.

At the summit, Ali also had to convince a group that had several members with a military background. Brown, as a member of the Army ROTC, graduated from Syracuse as a second lieutenant. Wooten completed his military obligation in 1960. Shorter served in a reserve unit, and Mitchell served with a military hospital unit in 1962. Beach spent four years in the Air Force. Stokes served in World War II, and McClinton served in the Army Signal Corps.

Brown didn’t set up a gauntlet for Ali. He also did not set up a meeting for Ali to waltz through.

“I wanted the meeting to be as intense and honest as it should’ve been, and it was because the people in that room had thoughts and opinions, and they came to Cleveland with that purpose in mind,” Brown said.

“We weren’t easy on him,” Mitchell said. “We weren’t slapping hands. In that room, especially early on, it got a little heated.”

How heated?

“F. Lee Bailey [a famous trial lawyer] would’ve been proud in the way we questioned the champ,” Wooten said. “Those guys shot questions at the champ, and he took them, and fought back. It was intense because we were all getting ready to face the United States public relations machine — the media, and put our lives and careers on the line. What if this fails? What if he goes to jail?”

Although it wasn’t discussed as a group before the meeting, many of the men planned to convince Ali to accept his call to the military.

“But after about 15 minutes of being there, I’m saying to myself, ‘No way is this guy going to change his mind,'” Davis said.

Ali made it clear that he would not participate in the Vietnam War. He spoke on Islam, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad, and black pride, but it all came down to his religious beliefs, and nothing was going to convince him otherwise.

“Jim told me that Ali talked for two straight hours,” Arum said. “And you have to understand that at that time, Ali was functionally illiterate. And here he was in a room with these great athletes who were all college educated, but he was able to convince all of them that the path he was taking was the correct one. And people at that point and time didn’t realize how smart Ali was.”

In fact, Ali was so convincing that many in the room nodded their heads in agreement whenever Ali made several points.

“The champ stood strong,” Wooten said.

“During those hours, he said he was sincere and his religion was important to him,” Mitchell said. “He convinced all of us, even someone like me, who was suspicious. We weren’t easy on him. We wanted Ali to understand what he was getting himself into. He convinced us that he was.”

McClinton also noted how the summit was not entirely about supporting Ali as a conscientious objector.

“Our presence there was more to the freedom for Ali to go left or right,” McClinton said.

“We didn’t have a right to tell Ali what to do,” Williams said. “All we could do is show our support for him in whatever he was going to do. That decision was up to him and he made it.”

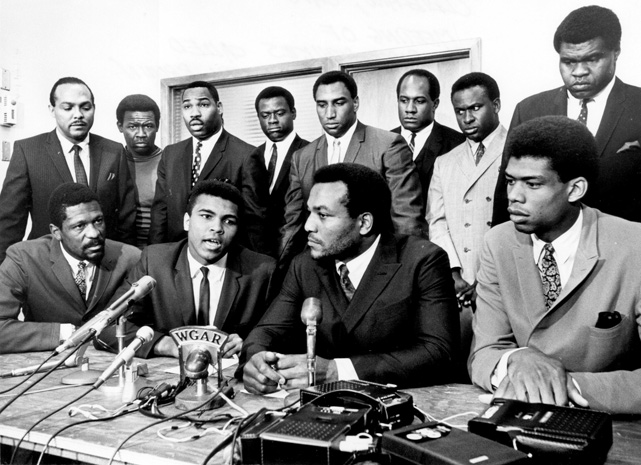

Following the meeting, Brown led the group to a press conference. Russell, Ali, Brown and Alcindor (Abdul-Jabbar) sat in the front row at a long table. Stokes, Beach, Williams, McClinton, Davis, Shorter, and Wooten stood behind them.

Brown said the group supported Ali and his rights as a conscientious objector. And they felt his sincerity.

Supporting Ali certainly wasn’t a popular move, but Brown and the others were willing to take the risk. None of the participants could cite any direct fallout when it came to supporting Ali, but being there for a friend was worth any risk.

“We didn’t care about any perceived threats,” Wooten said. “We weren’t concerned because we weren’t going to waver. We were unified. We all had a real relationship with each other and we knew we were doing something for the betterment of all.”

In an even broader sense, the Ali Summit — not known by that name at the time — helped to validate Ali’s religious beliefs. But those beliefs and the summit could not prevent the actions of the U.S. government two weeks later when Ali was convicted of draft evasion, sentenced to five years in prison, fined $10,000 and banned from boxing for three years. He stayed out of prison as his case was appealed. The Supreme Court would overturn the decision in 1971.

But the summit had other immeasurable benefits.

“We knew who we were,” said McClinton of the athletes who stood united 45 years ago. “We knew what we had woven into our country, and we stood at the highest level of citizenship as men. You name the value, we took the brush and painted it. You raised the bar, we reached it. You defined excellence, we supersede it. As a matter of fact, we defined it.”