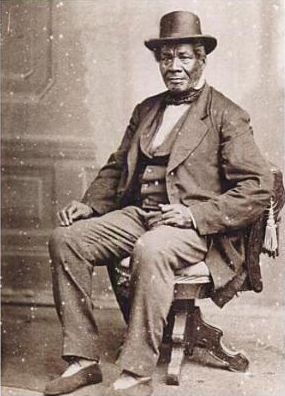

George Bonga (August 20, 1802 – 1880) was a fur trader of African-American and Ojibwe descent, one of the first African Americans born in what is now Minnesota. He was the second son of Pierre Bonga and an Ojibwe mother.

George was schooled in Montreal, Canada, becoming fluent in French as well as Ojibwe and English. He later became a fur trader and interpreter. He was noted in Minnesota for being, as his brother Stephen claimed, “One of the first two black children born in the state.” Stephen also described them as “the first white children” born there, as the Ojibwe classified everyone who was non-native as “white”.

In 1837 George Bonga tracked down a suspected murderer, an Ojibwe named Che-Ga Wa Skung, and brought him back to Fort Snelling. The ensuing criminal trial was reputedly the first in Minnesota, and the Ojibwe man was acquitted.

George Bonga was described as standing over six feet tall and weighing 200+ pounds. Reports said that he would carry 700 pounds of furs and supplies at once. He served as an interpreter, and was believed to have acted as a guide for governor Lewis Cass. Well respected in the region, Bonga and his wife opened a lodge on Leech Lake after the fur trade declined.

In 1802, George Bonga was born to Pierre Bonga, who was black, and his Ojibwe wife. His father, Pierre was the son of Jean and Marie-Jeannette Bonga, slaves who had been brought to the fort on Mackinac Island by their master, Captain Daniel Robertson, a British officer who commanded it from 1782 to his death in 1787. The couple were freed at his death and legally married. Bonga and his wife opened the first hotel on the island.

Pierre Bonga worked as a fur trader with the Anishinaabe near Duluth, Minnesota. His first son Stephen Bonga, born 1799, also became a notable fur trader and translator in the region. The sons had a sister Marguerite, born in 1797.

As Pierre Bonga was a relatively successful trader, he sent George to Montreal for school. When the youth returned to the Great Lakes region, he spoke fluent English, French, as well as Ojibwe.

Bonga followed in his father’s footsteps and became a fur trader with the American Fur Company. In this role, Bonga drew the attention of Lewis Cass, who hired him as a guide and as a translator for the government’s negotiations with the Anishinaabe. Bonga’s signature is on treaties in 1820 and 1867.

Bonga had gained an education among both European and Ojibwe societies, and frequently crossed their borders. Comfortable in white and Anishinaabe society, Bonga identified with both. Reportedly, Bonga called himself one of the first two “white men” in Northern Minnesota. He was speaking of his participation in ‘white’ culture. He criticized white men who treated Anishinaabe trappers unfairly. Bonga wrote letters on behalf of the Anishinaabe, complaining to the state government about individual Indian agents in the region. His letters, which point out both his connections to the white government and the Anishinaabe, illustrate the ways that Bonga traversed cultural boundaries.

In 1837 an Anishinaabe man, Che-ga-wa-skung, was accused of murdering a white man at Cass Lake, then known as Red Cedar Lake. Che-ga-wa-skung escaped from custody. Bonga trailed the man over five days and six nights during the winter, eventually catching him. He brought the suspect back to Fort Snelling for trial. In one of the first United States criminal proceedings in the Minnesota territory, Che-ga-wa-skung was tried and acquitted.

Bonga was unpopular with some Anishinaabe because of his role in the case, but he continued living with or near the people for the rest of his life. In 1842, he married Ashwinn, an Anishinaabe woman. They had four children together.

1842 marked the effective end of the American Fur Company. With the beaver nearly extinct and European fashions changing, the fur trade that had been Bonga’s livelihood had declined dramatically. In its place Bonga and his wife turned to lodge keeping. For many years, they welcomed travelers into their lodge on Leech Lake. Some travelers reported on Bonga’s telling stories of early Minnesota and singing for their enjoyment.

Bungo Township in Cass County is named after his family. Spelling varied widely at this time.