Henry “Box” Brown (c.1816–after 1889) was a 19th-century Virginia slave who escaped to freedom at the age of 33 by arranging to have himself mailed in a wooden crate in 1849 to abolitionists in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He left behind his enslaved wife and children.

For a short time Brown became a noted abolitionist speaker in the northeast United States. He lost the support of the abolitionist community, notably Frederick Douglass, who wished Brown had kept quiet about the details of his escape so that others could have used similar means. As a public figure and fugitive slave, Brown felt endangered by passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which increased pressure to capture escaped slaves. He moved to England and lived there for 25 years, touring with an anti-slavery panorama and becoming a mesmerist and showman. Mostly forgotten in the United States, he married an English woman and had a second family with her. He returned to the US with them in 1875 and continued to earn a living as an entertainer.

Henry Brown was born into slavery in 1816 in Louisa County, Virginia. At the age of 15 he was sent to work in a tobacco factory in Richmond. In his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself, he describes his owner: “Our master was uncommonly kind, (for even a slaveholder may be kind) and as he moved about in his dignity he seemed like a god to us, but notwithstanding his kindness although he knew very well what superstitious notions we formed him, he never made the least attempt to correct our erroneous impression, but rather seemed pleased with the reverential feelings which we entertained towards him.

Brown had married but his wife was also enslaved, and their marriage was not recognized legally. Their three children were born into slavery, under the partus sequitur ventrem principle. Brown was hired out by his master in Richmond, Virginia, and worked in a tobacco factory; he rented a house where he and his wife lived with their children. After his master sold his wife and children to a different slave owner, Brown said he received a “heavenly vision” to “mail [himself] to a place where there are no slaves.”

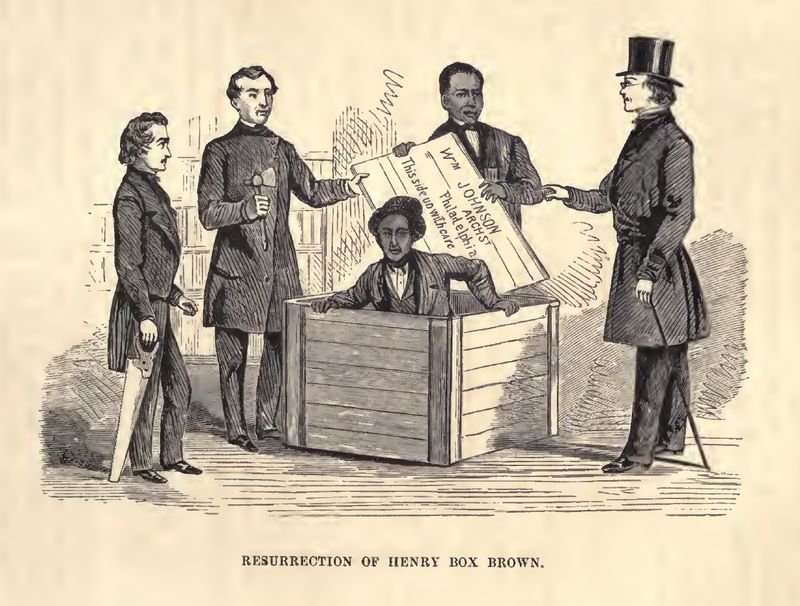

With the help of James C. A. Smith, a free black, and a sympathetic white shoemaker (and likely gambler) named Samuel A. Smith (no relation), Brown devised a plan to have himself shipped to a free state by Adams Express Company, known for its confidentiality and efficiency. Brown paid $86 (out of his savings of $166) to Samuel Smith. He went to Philadelphia to consult with members of Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society on how to accomplish the escape, meeting with minister James Miller McKim, William Still, and Cyrus Burleigh. He corresponded with them to work out the details after returning to Richmond. They advised him to mail the box to the office of Quaker merchant Passmore Williamson, who was active with the Vigilance Committee.

To get out of work the day he was to escape, Brown burned his hand to the bone with oil of vitriol (sulfuric acid). The box that Brown was shipped in was 3 feet long by 2 feet 8 inches deep by 2 feet wide and displayed the words “dry goods” on it. It was lined with baize, a coarse woolen cloth, and he carried only a small portion of water and a few biscuits. There was a single hole cut for air and it was nailed and tied with straps. Brown later wrote that his uncertain method of travel was worth the risk: “if you have never been deprived of your liberty, as I was, you cannot realize the power of that hope of freedom, which was to me indeed, an anchor to the soul both sure and steadfast.”

During the trip, which began on March 29, 1849, Brown’s box was transported by wagon, railroad, steamboat, wagon again, railroad, ferry, railroad, and finally delivery wagon, being completed in 27 hours. Despite the instructions on the box of “handle with care” and “this side up,” several times carriers placed the box upside-down or handled it roughly. Brown remained still and avoided detection.

The box was received by Williamson, McKim, William Still, and other members of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee on March 30, 1849, attesting to the improvements in express delivery services. When Brown was released, one of the men remembered his first words as “How do you do, gentlemen?” He sang a psalm from the Bible, which he had earlier chosen to celebrate his release into freedom.

Brown’s escape highlighted the power of the mail system, which used a variety of modes of transportation to connect the East Coast. Adams Express Company, founded in 1840, marketed its confidentiality and efficiency. It was favored by abolitionist organizations and “promised never to look inside the boxes it carried.”

Brown became a well-known speaker for the Anti-Slavery Society and got to know Frederick Douglass. He was nicknamed “Box” at a Boston antislavery convention in May 1849, and thereafter used the name Henry Box Brown. He published two versions of his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown; the first, written with the help of Charles Stearns and conforming to expectations of the slave narrative genre, was published in Boston in 1849. The second was published in Manchester, England, in 1851 after he had moved there.

Douglass wished that Brown had not revealed the details of his escape, so that others might have used it. The year of his escape, Brown was contacted by his wife’s new owner, who offered to sell his family to him, but the newly free man declined. This was an embarrassment within the abolitionist community, which tried to keep the information private.

After passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which required cooperation from law enforcement officials to capture refugee slaves even in free states, Brown moved to England for safety, as he had become a known public figure. He toured Britain with his antislavery panorama for the next 10 years, performing several hundred times a year. He visited nearly every town and city on the island during that period. To earn a living, Brown also entered the British show circuit for 25 years, until 1875, leaving the abolitionist circuit after the start of the American Civil War. In the 1860’s, he began performing as a mesmerist, and some time after that as a conjuror, under the show names of “Prof. H. Box Brown” and the “African Prince”.

In England Brown married a white British woman and began a new family. In 1875, he returned with his family to the U.S. with a group magic act. A later report documented the Brown Family Jubilee Singers.