Aaron Douglas (May 26, 1899 – February 3, 1979) was an African-American painter and a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Aaron Douglas was born in Topeka, Kansas, to Aaron and Elizabeth Douglas. He developed an interest in art during his childhood and was encouraged in his pursuits by his mother. Douglas graduated from Topeka High School in 1917. He received his B.A.degree from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 1922. In 1925, Douglas moved to New York City, settling in Harlem. Just a few months after his arrival he began to produce illustrations for both The Crisis and Opportunity, the two most important magazines associated with the Harlem Renaissance. He also began studying with Winold Reiss, a German artist who had been hired by Alain Locke to illustrate The New Negro. Reiss’s teaching helped Douglas develop the modernist style he would employ for the next decade. Douglas’s engagement with African and Egyptian design brought him to the attention of W. E. B. Du Bois and Dr. Locke, who were pressing for young African American artists to express their African heritage and African American folk culture in their art.

Douglas was heavily influenced by the African culture he painted for. His natural talent plus his newly acquired inspiration allowed Douglas to be considered the “Father of African American arts.” That title led him to say,” Do not call me the Father of African American Arts, for I am just a son of Africa, and paint for what inspires me.”

For the next several years, Douglas was an important part of the circle of artists and writers we now call the Harlem Renaissance. In addition to his magazine illustrations for the two most important African-American magazines of the period, he illustrated books, painted canvases and murals, and tried to start a new magazine showcasing the work of younger artists and writers. It was during the early 1930’s that Douglas completed the most important works of his career, his murals at Fisk University and at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture).

For the next several years, Douglas was an important part of the circle of artists and writers we now call the Harlem Renaissance. In addition to his magazine illustrations for the two most important African-American magazines of the period, he illustrated books, painted canvases and murals, and tried to start a new magazine showcasing the work of younger artists and writers. It was during the early 1930’s that Douglas completed the most important works of his career, his murals at Fisk University and at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture).

Throughout his early career, Douglas has gone looked for opportunities to increase his knowledge about art. In 1928–29, Douglas studied African and Modern European art at the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania on a grant from the foundation. In 1931 he traveled to Paris, where he spent a year studying more traditional French painting and drawing techniques at the Academie Scandinave.

In 1940, he moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he founded the Art Department at Fisk University and taught for  27 years. Coinciding with this move was a shift to a more traditional painting style, including portraits and landscapes like the one at right. Aaron Douglas has been called the father of African American art. His striking illustrations, murals, and paintings of the life and history of people of color depict an emerging black American individuality in a powerfully personal way. Working primarily from the 1920’s through the 1940’s, Douglas linked black Americans with their African past and proudly showed black contributions to society decades before the dawn of the civil rights movement. His work made a lasting impression on future generations of black artists.

27 years. Coinciding with this move was a shift to a more traditional painting style, including portraits and landscapes like the one at right. Aaron Douglas has been called the father of African American art. His striking illustrations, murals, and paintings of the life and history of people of color depict an emerging black American individuality in a powerfully personal way. Working primarily from the 1920’s through the 1940’s, Douglas linked black Americans with their African past and proudly showed black contributions to society decades before the dawn of the civil rights movement. His work made a lasting impression on future generations of black artists.

In the film Hidden Heritage: The Roots of Black American Painting, David C. Driskell—an artist and a leading educator and scholar of African American art—discussed Aaron Douglas’s role in art history: “Douglas is the leading painter of the [Harlem] Renaissance movement. A pioneering Africanist, he accepted the legacy of the ancestral arts of Africa and developed his own original style, geometric symbolism. At a time when it was unpopular to dignify the black image in white America, Douglas refused to compromise and see blacks as anything less than a proud and majestic people.”

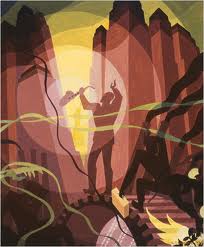

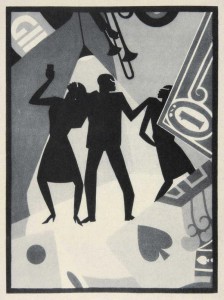

Best represented by black-and-white drawings with black silhouetted figures, as well as by portraits, landscapes, and murals, Douglas’s art fused modernism with ancestral African images, including fetish motifs, masks, and artifacts. His work celebrates African American versatility and adaptability, depicting people in a variety of settings—from rural and urban scenes to churches to nightclubs. His illustrations in books by leading black writers established him as the black artist of the period. Later in his career, Douglas founded the Art Department at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Beginning in the 1920’s, Douglas’s illustrations appeared in books by James Weldon Johnson, Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, and other prominent black writers, activists, and intellectuals. They were also featured in such magazines as The Crisis, Opportunity, Harper’s, and Vanity Fair. From the late 1920’s through the 1940’s, his art was shown across the United States at universities, galleries, hotels, and museums, including the Harmon Foundation in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Dallas, Howard University’s Gallery of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and New York’s Gallery of Modern Art. In addition, selected works by Douglas were assembled for a landmark traveling show of Harlem Renaissance artworks sponsored by the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1988. According to Driskell in an essay for Harlem Renaissance Art of Black America, “It was Douglas’s own strength of character and inventive artistry that enabled him to have a lasting impact on the future course of black expression in art.” In A History of African American Artists from 1792 to the Present by Romare Bearden and Harry Henderson, Douglas was quoted as saying, “One day [my mother] came home with a magazine [containing] a reproduction of a painting by [black artist Henry O. Tanner]. It was his painting of Christ and Nicodemus meeting in the moonlight on a rooftop. I remember the painting very well. I spent hours poring over it, and that helped to lead me to deciding to become an artist.” Years later, Douglas visited Tanner in Paris.

Beginning in the 1920’s, Douglas’s illustrations appeared in books by James Weldon Johnson, Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, and other prominent black writers, activists, and intellectuals. They were also featured in such magazines as The Crisis, Opportunity, Harper’s, and Vanity Fair. From the late 1920’s through the 1940’s, his art was shown across the United States at universities, galleries, hotels, and museums, including the Harmon Foundation in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Dallas, Howard University’s Gallery of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and New York’s Gallery of Modern Art. In addition, selected works by Douglas were assembled for a landmark traveling show of Harlem Renaissance artworks sponsored by the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1988. According to Driskell in an essay for Harlem Renaissance Art of Black America, “It was Douglas’s own strength of character and inventive artistry that enabled him to have a lasting impact on the future course of black expression in art.” In A History of African American Artists from 1792 to the Present by Romare Bearden and Harry Henderson, Douglas was quoted as saying, “One day [my mother] came home with a magazine [containing] a reproduction of a painting by [black artist Henry O. Tanner]. It was his painting of Christ and Nicodemus meeting in the moonlight on a rooftop. I remember the painting very well. I spent hours poring over it, and that helped to lead me to deciding to become an artist.” Years later, Douglas visited Tanner in Paris.

Douglas received a B.F.A. from the University of Nebraska in 1922 and a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Kansas the next year. Commenting on his days at the University of Nebraska, where he won a prize for drawing, he recalled: “I was the only black student there. Because I was sturdy and friendly, I became popular with both faculty and students.” His ability to get along notwithstanding, Douglas longed to draw from an undraped model and felt constrained by the “Victorian attitudes” that prevented the school from using nudes in the classroom.

The style Aaron Douglas developed in the 1920’s synthesized aspects of modern European, ancient Egyptian, and West African art. His best-known paintings are semi-abstract, and feature flat forms, hard edges, and repetitive geometric shapes. Bands of color radiate from the important objects in each painting, and where these bands intersect with other bands or other objects, the color changes.