Happy Wednesday POU!

Today’s entry in our political prisoners profiles has an interesting twist. Veronza Bowers would have been granted parole but an intervention by a member of the Bush Administration revoked the parole and he has remained in prison despite being a model prisoner.

First, the background:

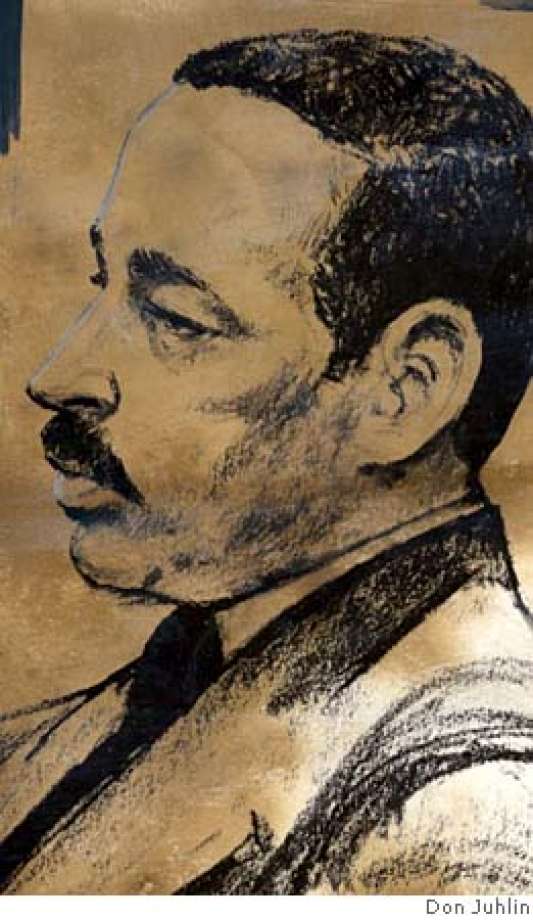

On September 15, 1973, Veronza Bowers, Jr. was arrested in Mill Valley, California and charged with robbery and possession of stolen property. After state charges were dropped for lack of probable cause to obtain a search warrant, the FBI arrested Bowers and charged him with the first-degree murder of National Park Service ranger Kenneth Patrick on August 5, 1973 at Point Reyes National Seashore near San Francisco.

At trial, testimonies from two government informants, Alan Veale and Jonathan Shoher, proved crucial. Both were also charged with the killing. Yet there were no independent eye-witnesses, and no evidence incriminated Bowers besides the word of these two men who had every incentive to cooperate with the Department of Justice.

Veale and Shoher were convicted bank robbers. In return for their testimony, their murder charges were dropped, and one of them served no prison time, was paid $10,000, and placed in the government’s witness protection program.

Allegations were that the three men were at Point Reyes National Seashore to poach deer, ranger Patrick confronted them, and Bowers shot him three times. At trial, he testified for himself and steadfastly denied the charge. His wife’s alibi testimony was dismissed as well as assertions by two relatives of the informants who insisted they were lying.

In April 1974, Bowers was convicted in San Francisco District Court and sentenced to life in prison.

The following is from the Washington Post, May 26, 2009

Allegations of Impropriety Surround Parole Commission

Like Washington’s most famous tale of intrigue, this one includes the surreptitious entry of an office on a weekend.

The incident at the U.S. Parole Commission, a little-noticed corner of the federal government, was certainly no Watergate. But it was one in a string of curious events that have unfolded quietly in recent years at the small but powerful commission.

Memos, e-mails and court records spin a yarn of internal discord that threads together the unauthorized entry, an old murder outside San Francisco, a commissioner’s resignation and attempts to win funding to improve a rural highway in Missouri. Players in the drama include a former special assistant to President George W. Bush, a past member of the Black Panthers and even a former Justice Department official who oversaw the politically tinged dismissal of nine U.S. attorneys.

The Parole Commission’s future has been in question since 1984, when Congress voted to eliminate federal parole and establish formal sentencing guidelines. The commission still has a multimillion-dollar budget and nearly 80 employees at its headquarters in a nondescript office building in Chevy Chase. It has survived attempts by lawmakers to eliminate it because it also handles inmates convicted under D.C. law and because some convicts sent away under the old federal system still need to have their cases heard.

One such inmate is Veronza Bowers Jr. After serving 31 years on a murder conviction, Bowers was granted parole and was preparing to walk out of a U.S. penitentiary in Florida in June 2005 when he and his family in the District learned that his release was on hold and that he would remain imprisoned indefinitely.

It later turned out that one of the commissioners, former White House aide Deborah Spagnoli, had contacted the office of then-Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales, who made an unprecedented intervention in the case. Attorneys for Bowers argue that Spagnoli created a secret back channel in an improper effort to keep Bowers in prison, even though the commission was designed to be a quasi-judicial, impartial body.

Spagnoli, who resigned from the commission in 2007, said all of her actions were consistent with her duty to make sure the commission considered all the facts about Bowers, whom she described as an “unrepentant murderer.”

“I never pre-judged the case, however, after my review of the specific facts and after applying the correct law, I made an independent judgment” that Bowers did not qualify for release, she said in a statement. She said she simply made that judgment clear in a 14-page memo to Gonzales, which she said she never intended to hide from her colleagues.

The Bowers episode preceded more trouble. In June 2006, on Father’s Day, someone surreptitiously entered the office of Parole Commission Chairman Edward F. Reilly Jr. and apparently copied dozens of pages from his files, records show.

Then things got really strange. Late last year, an anonymous letter and a package of documents were sent to the Justice Department’s inspector general, alleging that Reilly was using his position and official stationery to promote improvements for a Missouri highway that could benefit his family holdings back home. Spagnoli’s husband, William Woodruff, now an assistant U.S. attorney in the District, confirmed to The Washington Post that he sent the package. He said he had obtained the documents through a Freedom of Information Act request in an attempt to gather evidence of what he thought were unethical practices.

Reilly said he was not trying to personally profit from his public position. He declined to discuss the Bowers case or the unauthorized entry of his office in detail.

Spagnoli, who began her career prosecuting violent offenders in Bakersfield, Calif., said that she had nothing to do with her husband’s investigation and that she had done nothing wrong.

“I am a prosecutor, and I came from the White House,” said Spagnoli, who was a special assistant to Bush and who was appointed by him to the Parole Commission in 2004.

“I thought what they were doing was just a disgrace. They were letting very bad criminals back on the street without any review. They didn’t follow proper procedure, et cetera. I just came in and had a different perspective. . . . We tried to make it more victim-oriented.”

Others argue that the Bowers matter alone points to serious problems at the commission.

“It is an outrageous case,” said Alan J. Chaset, a lawyer and former employee of the commission who at one time represented Bowers. “They played fast and loose with the laws.”

Reilly’s tenure as head of the commission is at an end. Last Tuesday, President Obama designated commission member Isaac Fulwood, a former D.C. police chief, as the new chairman.

A Park Ranger Is Killed

Opponents of Bowers’s parole say there was good reason to keep him behind bars. Bowers, who had been a member of the Black Panthers in California in the early 1970s, first came up for what is known as mandatory parole in 2004. Bowers had to be paroled after 30 years unless it was determined that he “seriously or frequently” violated prison rules or that there was a reasonable probability he would commit a crime.

His criminal case dates to 1973, when he and two friends allegedly packed up crossbows and headed to the Point Reyes National Seashore outside San Francisco to poach deer. Early on the morning of Aug. 5, according to trial testimony, Kenneth Patrick, a National Park Service ranger and father of three, approached through the fog and shined a flashlight into their Pontiac Grand Prix. Someone fired a 9mm handgun, killing Patrick. One man in the car later identified the shooter as Bowers.

Bowers has always contended that he was asleep in his bed at the time. He has called himself “one of the longest-held political prisoners in the U.S.” His supporters set up a Web site, established a defense fund and sold CDs of his Japanese flute performances.

By early 2005, hearing examiners had reviewed his case and deemed him a good candidate for release. That led to an order for his parole, which often results in an inmate’s release without any action by the full commission. Instead of abiding by that order, Spagnoli called for a vote by all the commissioners.

The vote resulted in a 2 to 2 tie, with one abstention, in May 2005, which by law meant the hearing examiners’ judgment would prevail. Bowers was told he would be freed.

Spagnoli did not give up. She e-mailed and talked to Justice Department officials, including Steven G. Bradbury, a former top lawyer in the Office of Legal Counsel, now best known for memos that authorized the CIA to use harsh interrogation techniques. According to court records, she also indicated that she had contacted D. Kyle Sampson, who went on to become Gonzales’s chief of staff and oversaw the dismissal of nine U.S. attorneys, a matter that is under criminal investigation.

Sampson and Bradbury declined to comment.

Without the knowledge of the other commissioners, records obtained by The Post show, Spagnoli wrote the memo to Gonzales’s office outlining legal arguments that he could use if he stepped into the Bowers case. Gonzales then made a request for a review of the case. It would be two years before other commissioners or Bowers’s attorneys learned about Spagnoli’s memo, records show.

Spagnoli did not specifically request that Gonzales intercede, but she indicated that she would vote against Bowers’s parole if he did step in. Spagnoli also pointed out that the Fraternal Order of Police, which opposed Bowers’s release, had more than 318,000 members. Around the same time, the group, which had been in contact with the widow of the slain park ranger, sent a letter to the attorney general arguing that Bowers was “an unrepentant murderer and career criminal.”

“I do not see a downside to an Appeal by the Attorney General,” Spagnoli wrote. “By requesting that the commission review its decision, the AG gets credit for doing so with crime victims and law enforcement” and “the Attorney General gets credit for protecting the public from a dangerous criminal.”

Although the commission’s administrative affairs are handled by the Justice Department, Congress designated it to be “insulated from political pressures, particularly pressures from the ‘prosecutorial arm’ of the Department,” according to the commission’s reference manual. The commission’s ethics guidebook says that members “should always maintain the impartiality of a judge” and should not be influenced by private contacts with one side in a dispute or by “any contact outside official channels.”

In recent court filings, government lawyers acknowledged that Spagnoli may have given the appearance that “she was not an impartial decision-maker.” But they also insist that her actions did not result in the commission’s change of position on Bowers. (cont’d to page 2)