Good Morning POU! Today’s highlight is the daring tale of how a slave seized a Confederate Ship and delivered it to the Union Army.

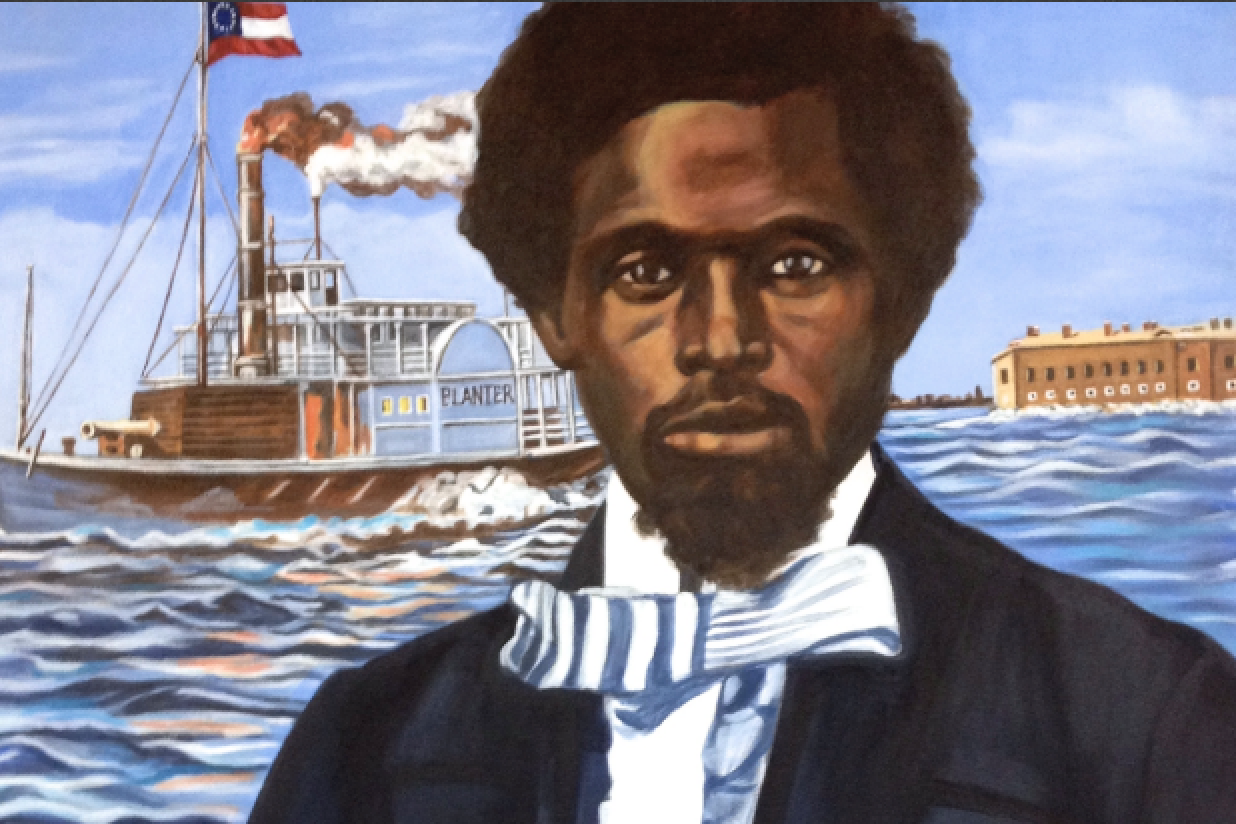

Darkness still blanketed the city of Charleston in the early hours of May 13, 1862, as a light breeze carried the briny scent of marshes across its quiet harbor. Only the occasional ringing of a ship’s bell competed with the sounds of waves lapping against the wooden wharf where a Confederate sidewheel steamer named the Planter was moored. The wharf stood a few miles from Fort Sumter, where the first shots of the Civil War had been fired just a little more than a year before.

As thin wisps of smoke rose from the vessel’s smokestack high above the pilothouse, a 23-year-old enslaved man named Robert Smalls stood on the deck. In the next few hours, he and his young family would either find freedom from slavery or face certain death. Their future, he knew, now depended largely on his courage and the strength of his plan.

Like so many enslaved people, Smalls was haunted by the idea that his family—his wife, Hannah; their four-year-old daughter, Elizabeth; and their infant son, Robert, Jr.—would be sold. And once separated, family members often never saw each other again.

The only way Smalls could ensure that his family would stay together was to escape slavery. This truth had occupied his mind for years as he searched for a plan with some chance of succeeding. But escape was hard enough for a single man; to flee with a young family in tow was nearly impossible: enslaved families often did not live or work together, and an escape party that included children would slow the journey significantly and make discovery much more likely. Traveling with an infant was especially risky; a baby’s cry could alert the slave patrols. And the punishment if caught was severe; owners could legally have runaways whipped, shackled, or sold.

Now Smalls’ chance at freedom had finally come. With a plan as dangerous as it was brilliant, he quietly alerted the other enslaved crew members on board. It was time to seize the Planter.

Smalls’ plan was to commandeer the Planter and deliver it to the imposing fleet of Union ships anchored outside Charleston Harbor. These vessels were part of the blockade of all major Southern ports President Abraham Lincoln had initiated shortly after Fort Sumter fell in April 1861. As one of the largest ports in the Confederacy, Charleston was a lifeline for the South. A largely agrarian society, the South depended on imports of war materiel, food, medicine, manufactured goods, and other supplies. With the U.S. Navy blocking the harbor, daring blockade runners, looking to make hefty profits, smuggled these goods into Charleston and carried cotton and rice out of the city for sale in European markets. After supplies arrived in Charleston, the city’s railroad connections delivered them throughout the Confederate states.

Although crucial, blockading such an important port was a staggering task. The many navigable channels in and out of the harbor made stopping all traffic nearly impossible and had led Northerners to refer to Charleston as a “rat hole.” Although many vessels outran and outmaneuvered the blockade, the Union was able to intercept some and either capture or destroy them.

Though the wharf and the U.S. fleet were only about ten miles apart, Smalls would have to pass several heavily armed Confederate fortifications in the harbor as well as multiple gun batteries along the shore without raising an alarm. The risk of discovery and capture was high.

The Planter created so much smoke and noise that Smalls knew that steaming past the forts and batteries undetected would be impossible. The ship had to appear to be on a routine mission under the command of its three white officers who were always on board when it was underway. And Smalls had come up with an inspired way to do just that. Protected by the darkness of the hour, Smalls would impersonate the captain.

This relatively simple plan presented multiple dangers. First, the three white officers posed an obvious obstacle, and Smalls and his crew would have to find a way to deal with them. Second, they would have to avoid detection by the guards at the wharf as they seized the Planter. Then, since Smalls’ family and others involved in the escape would be hiding in another steamer farther up the Cooper River, Smalls and the remaining crew would have to backtrack away from the harbor’s entrance to pick them up. The Planter’s movement up the river and away from the harbor was likely to attract the attention of sentries posted among the wharves. If everyone made it on board, the party of 16 men, women, and children would then have to steam through the heavily guarded harbor. If sentries at any of the fortifications or batteries realized something was amiss, they could easily destroy the Planter in seconds.

Once safely through the harbor, Smalls and company faced yet another big risk: approaching a Union ship, which would have to assume the Confederate steamer was hostile. Unless Smalls could quickly convince the Union crew that his party’s intentions were friendly, the Union ship would take defensive action and open fire, likely destroying the Planter and killing everyone on board.

Clearing any one of these obstacles would be a remarkable feat, but clearing all of them would be astounding. Despite the enormous risks, Smalls was ready to forge ahead for the sake of his family and their freedom.

For the past year Smalls had been a trusted and valued member of the Planter’s enslaved crew. Although Smalls had become known as one of the best pilots in the area, the Confederates refused to give him, or any enslaved man, the title of pilot.

Smalls was part of a crew of ten that included three white officers—the captain, Charles J. Relyea, 47; the first mate, Samuel Smith Hancock, 28; and the engineer, Samuel Z. Pitcher, 34.

In addition to Smalls, the rest of the crew included six other enslaved black men who ranged in age from their teens to middle-age and acted as engineers and deckhands. John Small, no relation, and Alfred Gourdine served as engineers, while the deckhands were David Jones, Jack Gibbes, Gabriel Turner and Abraham Jackson.

As the new captain of the Planter, Relyea occasionally left the ship in the hands of the black crew overnight so he and his officers could stay with their wives and children in their homes in the city. Relyea may have done so because he trusted his crew, but it is more likely that he, like many whites in the South, and even the North, simply did not think that enslaved men would be capable of pulling off a mission as dangerous and difficult as commandeering a Confederate vessel. It would be nearly impossible for anyone to take a steamer in a harbor so well guarded and difficult to navigate; few whites at the time could imagine that enslaved African-Americans would be able to do it.

By leaving the ship in the crew’s care, Relyea was violating recent Confederate military orders, General Orders, No. 5, which required white officers and their crews to stay on board, day and night, while the vessel was docked at the wharf so they could be ready to go at any minute. But even beyond his decision to leave the crew alone with the ship, Relyea himself was a key element of Smalls’ plan.

When Smalls told Hannah about his idea, she wanted to know what would happen if he were caught. He did not hold back the truth. “I shall be shot,” he said. While all the men on board would almost certainly face death, the women and children would be severely punished and perhaps sold to different owners.

Hannah, who had a kind face and a strong spirit, remained calm and decisive. She told her husband: “It is a risk, dear, but you and I, and our little ones must be free. I will go, for where you die, I will die.” Both were willing to do whatever it took to win their children’s freedom.

Smalls, of course, also had to approach his fellow crew members. Sharing his plan with them was in itself a huge risk. Even talking about escape was incredibly dangerous in Confederate Charleston. Smalls, however, had little choice in the matter. His only option was to recruit the men and trust them.

The crew met secretly with Smalls sometime in late April or early May and discussed the idea, but their individual decisions could not have been easy. All knew that whatever they decided in that moment would affect the rest of their lives. It was still quite possible that the Confederacy would win the war. If it did, staying behind meant enduring lives of servitude. The promise of freedom was so strong, and the thought of remaining in slavery so abhorrent, that these considerations ultimately convinced the men to join Smalls. Before the meeting ended, all had agreed to take part in the escape and to be ready to act whenever Smalls decided it was time.

It would be a remarkable feat. Most enslaved men and women trying to reach the Union fleets blockading Southern ports rowed to the vessels in canoes. No civilian, black or white, had ever taken a Confederate vessel of this size and turned it over to the Union. Nor had any civilian ever delivered so many priceless guns.

Just a few weeks earlier, a group of 15 slaves in Charleston had surprised the city by seizing a barge from the waterfront and rowing it to the Union fleet. The barge belonged to General Ripley, the same commander who used the Planter as his dispatch boat. When it was found to be missing, the Confederates were furious. They were also embarrassed at being outsmarted by slaves. Nonetheless, they failed to take any extra precautions in securing other vessels at the wharf.

Smalls quietly let the men know his intentions. As the reality of what they were about to do descended on them, they were overwhelmed by fears of what might happen. Even so, they pressed forward.

When Smalls judged the time was right, he ordered the steamer to leave. The fog was now thinning, and the crew raised two flags. One was the first official Confederate flag, known as the Stars and Bars, and the other was South Carolina’s blue-and-white state flag, which displayed a Palmetto tree and a crescent. Both would help the ship maintain its cover as a Confederate vessel.

The Confederate guard stationed about 50 yards away from the Planter saw the ship was leaving, and even moved closer to watch her, but he assumed the vessel’s officers were in command and never raised an alarm. A police detective also saw that the ship was leaving and made the same assumption. Luck seemed to be on Smalls’ side, at least for now.

The Planter’s next task was to stop at the North Atlantic Wharf to pick up Smalls’ family and the others. The crew soon reached the North Atlantic Wharf and had no trouble approaching the pier. “The boat moved so slowly up to her place we did not have to throw a plank or tie a rope,” Smalls said.

All had gone as planned, and they were now together. With 16 people on board, and the women and children belowdecks, the Planter resumed her way south toward Confederate Fort Johnson, leaving Charleston and their lives as slaves behind them.

At about 4:15 a.m., the Planter finally neared the formidable Fort Sumter, whose massive walls towered ominously about 50 feet above the water. Those on board the Planter were terrified. The only one not outwardly affected by fear was Smalls. “When we drew near the fort every man but Robert Smalls felt his knees giving way and the women began crying and praying again,” Gourdine said.

As the Planter approached the fort, Smalls, wearing Relyea’s straw hat, pulled the whistle cord, offering “two long blows and a short one.” It was the Confederate signal required to pass, which Smalls knew from earlier trips as a member of the Planter’s crew.

The sentry yelled out, “Blow the d—d Yankees to hell, or bring one of them in.” Smalls must have longed to respond with something hostile, but he stayed in character and simply replied, “Aye, aye.”

With steam and smoke belching from her stacks and her paddle wheels churning through the dark water, the steamer headed straight toward the closest of the Union ships, while her crew rushed to take down the Confederate and South Carolina flags and hoist a white bedsheet to signal surrender.

Meanwhile another heavy fog had quickly rolled in, obscuring the steamer and its flag in the morning light. The crew of the Union ship they were approaching, a 174-foot, three-masted clipper ship named the Onward, was now even more unlikely to see the flag in time and might assume a Confederate ironclad was planning to ram and sink them.

As the steamer continued toward the Onward, those aboard the Planter began to realize their improvised flag had been seen. Their freedom was closer than ever.

The two vessels were now within hailing distance of one another, and the Onward’s captain, acting volunteer lieutenant John Frederick Nickels, yelled for the steamer’s name and her intent. After the men supplied the answers, the captain ordered the ship to come alongside. Whether because of their relief that the Onward had not fired or because Smalls and his crew were still quite shaken, they did not hear the captain’s command and started to go around the stern. Nickels immediately yelled, “Stop, or I will blow you out of the water!”

The harsh words jolted them to attention, and the men maneuvered the steamer alongside the warship.

As the crew managed the vessel, those on board the Planter realized they had actually made it to a Union ship. Some of the men began jumping, dancing, and shouting in an impromptu celebration, while others turned toward Fort Sumter and cursed it. All 16 were free from slavery for the first time in their lives.

Smalls then spoke triumphantly to the Onward’s captain: “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!—that were for Fort Sumter, sir!”

From Be Free or Die by Cate Lineberry, copyright © 2017