Good Morning POU!

Today we look at one of the premiere Miss Anne’s of the Harlem Renaissance. She provided the resources for many black writers of the period to pursue their talents, chief among them Zora Neal Hurston. Of course as we well know, that support did not come without its own price.

Charlotte Osgood Mason, born Charlotte Louise Van der Veer Quick (May 18, 1854 – April 15, 1946) was an American socialite and philanthropist…and the epitome of the “Miss Anne”.

She came from a rich family and her wealth increased after the death of her husband Rufus Osgood Mason. She used her wealth to support artists such as Aaron Douglas, Langston Hughes, Arthur Fauset, and Miguel Covarrubias of the Harlem Renaissance, and in particular Zora Neale Hurston.

According to Zora Neale Hurston’s autobiography Dust Tracks On a Road, Mrs. Mason, who insisted upon being called Godmother the group of New Negroes she patronized, was “extremely human.”

Mason had spent most of her life interested in the folklore of non-white races. In the early 1900’s she spent months living amongst the Plains Indians (no doubt getting on their last nerves). At the height of the Harlem Renaissance, Mason became interested, both financially and personally, with the development of New Negro Artists such as Hurston, Langston Hughes and Miguel Covarrubias.

According to Langston Hughes, Mason had in the 1920s ” discovered the New Negro and wanted to help him,” not because she wanted to see the black race excel, but because she saw African Americans as “America’s great link with the primitive.” In order to get her fill of the primitive she turned to Alain Locke, who furnished her with the artists capable of supplying evidence of “black primitivism” in their work.

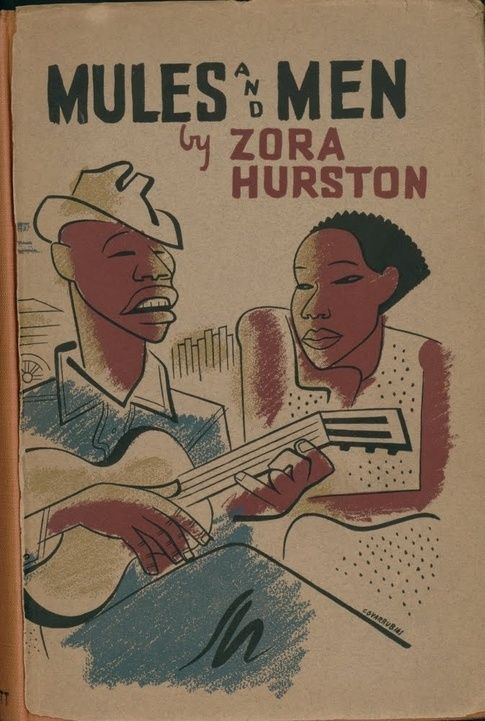

Mules and Men is a 1935 autoethnographical collection of African American folklore collected and written by anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston. The research for the collection was financed by Osgood, who insisted on putting her “stamp” on the works.

In the Mules and Men Hurston characterizes Mason as a “Great Soul,” and “the worlds most gallant woman,” yet like every statement made by Hurston, this one needs to be taken with a grain of salt. When Charlotte Mason agreed to finance Hurston’s folklore collecting expeditions, she made several demands on the young artist. Most importantly, the text itself and all the material gathered by Hurston were to belong to Mason. The contract that Hurston signed suggests the controlling nature of their relationship, for the two hundred dollar a month stipend Hurston had to agree not to publish any of the material that she gathered. The contract implied the Hurston was merely Mason’s representative, that in fact Mason herself was the true collector.

Eventually Hurston’s involvement with Mrs. Mason proved confining. If her tales failed to express the desired “primitive” elements in their work then she was denied support. As Hurston explained: “There she was sitting up there at the table over the capon, caviar and gleaming silver, eager to hear every word on every phase of life on a saw-mill “job.” I must tell the tales, sing the songs, do the dances, and repeat the raucous sayings and doings of the Negro furthest down”. Langston Hughes too severed his relationship with Mason because, as he too recounts, “she wanted me to be primitive and know and feel the intuitions of the primitive. But, unfortunately, I did not feel the rhythms of the primitive surging through me, and so I could not live and write as though I did. I was only an American Negro–who had loved the surface of Africa and the rhythms of Africa–but I was not Africa”.

Hurston’s connection with Mason was severed soon after her return to New York. Yet, Mules and Men still bears her mark. Mason shared Hurston’s interest in Hoodoo and agreed to additionally finance her trip to New Orleans following her expedition to Florida. The frequent collaborations via letters between Hurston and her wealthy patron suggest that Mason made a wide variety of suggestions in terms of the construction of the text. Mason insisted that Hurston tone down the “dirty words” in order to make the text “more presentable”.

“Grabbing Our Stuff and Ruining It”

During the 1920s, literature exploded throughout the country, with authors gaining increasing popularity and social cache from New York City to San Francisco. However, black writers were dismayed to find that there were white writers who felt they knew more about the black experience in this country than the very people whose skin lived it each and every day.

Believing that accurate representations of blacks would turn the tide of American racism, black artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance “promoted poetry, prose, painting and music as if their lives depended on it.” In the words of diplomat, writer, editor, and activist James Weldon Johnson, “the final measure of the greatness of all peoples is the amount and standard of the literature and art they have produced. . . . ‘Through his artistic efforts the Negro is smashing the race barriers faster than he has ever done through any other method.’” Given those stakes, it should not be surprising that Harlem’s black writers watched with dismay as white writers including Gertrude Stein, Sherwood Anderson, Waldo Frank, Carl Van Vechten, Paul Green, Eugene O’Neill, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Fannie Hurst became more successful for depicting black life than they were.

Resentment over the ubiquity of such attitudes was keen. But bad feeling also had to be handled with care. Hurston, for example, freely told her best friend, Langston Hughes, “It makes me sick to see how these cheap white folks are grabbing our stuff and ruining it. I am almost sick—my one consolation being that they never do it right and so there is still a chance for us.”

But when she repeated those sentiments to her benefactor Charlotte Osgood Mason, writing to Mason that white people “take all the life and soul out of everything,” Mason took offense. Hurston had to backpedal or give up Mason’s help. Indeed, Hurston’s anger, though shared by almost every other black Harlemite, was usually not made public. Most black artists in Harlem were surrounded by influential or moneyed whites whose feelings needed to be taken into account.

For white women the enticements of black literary impersonation were particularly strong and the rewards especially rich. White women writers in the 1920s were still fighting author Nathaniel Hawthorne’s description of them as “scribblers” and gossipers. So the vogue for novels about black life opened an important literary door for them. Dorothy Fields, Dorothy Parker, Rebecca West, Pearl Buck, Helen Worden Erskine, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Florine Stettheimer, Anne Pennington, Muriel Draper, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Hallie Flanagan, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Ethel Barrymore, and Libby Holman all took advantage of “the vogue.”

Miss Anne’s view of blacks was not always appreciated by those she wrote about. But because “Negroes are practically never rude to white people,” as Langston Hughes noted, the record of such responses is scant. Many black women, especially, chose to respond to Miss Anne’s portrayals of them with either silence or exaggerated, ironic flattery in place of a more direct critique. There were occasional political cartoons of white women, but not as many as one might expect, and most of them, such as those included here, were both relatively benign and printed anonymously.

One way to deal with Miss Anne and her portrayals of blacks was to respond to her in kind, embedding depictions of white women into black literature. In contrast to the histories of the period, in which Miss Anne hardly appears, and black writings, including correspondence, in which she’s hardly mentioned, the fiction of the Harlem Renaissance is riddled with depictions of Miss Anne. Almost always, she appears either as a fool or as a monster. Those depictions were a powerful part of the Harlem world that Miss Anne entered.

Rudolph Fisher’s Agatha Cramp, for example, is based on Charlotte Osgood Mason, and as a caricature, it pulls no punches. Miss Cramp is “the homeliest woman in the world,” with a “large store of wealth” and a “small store of imagination.” Miss Cramp decides that there’s “a great work” for her to do in Harlem, notwithstanding the fact that she knows nothing about black culture and has met no black people other than “porters, waiters, and house-servants of acquaintances.” But enamored of her own “vision” of blacks, she sees an “alien, primitive people” who need her, she believes. Wallace Thurman also created a recognizable caricature in Barbara Nitsky, who appears in his 1932 novel Infants of the Spring. Nitsky seems an exotic and appealing woman, but as it turns out, she is just another “Jewish girl who had been born in the Bronx, sophisticated in Greenwich Village . . . and then migrated to Harlem, broke and discouraged, to discover that among Negro men she could be enthroned and honored like a queen of the realm.”