Good morning, POU! It’s humpday, continuing on with this week’s theme, I am highlighting the role of Jim Crow during the nadir of race relations.

White supremacy

As noted above, white paramilitary forces contributed to whites’ taking over power in the late 1870s. A brief coalition of populists took over in some states, but conservative Democrats had returned to power after the 1880s. From 1890 to 1908, they passed legislation and constitutional amendments to disenfranchise most blacks and many poor whites, with Mississippi and Louisiana creating new state constitutions in 1890 and 1895 respectively, to disenfranchise African Americans.

Democrats used a combination of restrictions on voter registration and voting methods, such as poll taxes, literacy and residency requirements, and ballot box changes. The major push came from elite Democrats in the Solid South, where blacks were a majority of voters. The elite Democrats also acted to disenfranchise poor whites. African Americans were an absolute majority of the population in Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina, and represented over 40% of the population in four other former Confederate states. Many whites perceived African Americans as a major political threat because, in free and fair elections, they would hold the balance of power in a majority of the South. South Carolina U.S. Senator Ben Tillman proudly proclaimed in 1900, “We have done our level best [to prevent blacks from voting]… we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them. We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it.”

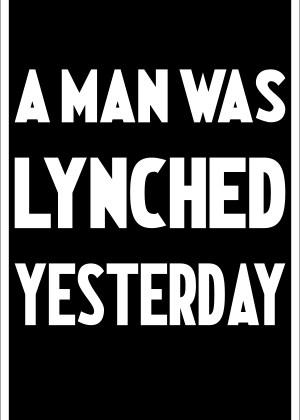

Conservative white Democratic governments passed Jim Crow legislation, creating a system of legal racial segregation in public and private facilities. Blacks were separated in schools and the few hospitals were restricted in seating on trains and had to use separate sections in some restaurants and public transportation systems. They were often barred from some stores or forbidden to use lunchrooms, restrooms, and fitting rooms. Because they could not vote, they could not serve on juries, which meant they had little if any legal recourse in the system. Between 1889 and 1922, as political disenfranchisement and segregation were being established, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) calculates lynchings reached their worst level in history. Almost 3,500 people fell victim to lynching, almost all of them black men.

Lynchings

Historian James Loewen notes that lynching emphasized the powerlessness of blacks: “The defining characteristic of lynching is that the murder takes place in public, so everyone knows who did it, yet the crime goes unpunished.” Ostensibly prompted by black attacks or threats to white women, scholars and journalists have shown that lynchings arose out of economic competition and desire by competing whites for social control. African American civil rights activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett conducted one of the first systematic studies of the subject. She found blacks were “lynched for anything or nothing”–for wife-beating, stealing hogs, being “saucy to white people”, sleeping with a consenting white woman–for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. It was a system of social terrorism.

Blacks who were economically successful faced reprisals or sanctions. When Richard Wright tried to train to become an optometrist and lens-grinder, the other men in the shop threatened him until he was forced to leave. In 1911 blacks were barred from participating in the Kentucky Derby because African Americans won more than half of the first twenty-eight races. Through violence and legal restrictions, whites often prevented blacks from working as common laborers, much less than skilled artisans or in the professions. Under such conditions, even the most ambitious and talented black people found it difficult to advance.

This situation called into question the views of Booker T. Washington, the most prominent black leader during the early part of the nadir. He had argued that black people could better themselves through hard work and thrift. He believed they had to master basic work before going on to college careers and professional aspirations. Washington believed his programs trained blacks for the lives they were likely to lead and the jobs they could get in the South.

However, as W. E. B. Du Bois pointed out,

“It is utterly impossible, under modern competitive methods, for working men and property-owners to defend their rights and exist without the right of suffrage.”

Washington had always (though often clandestinely) supported the right of black suffrage, and had fought against disfranchisement laws in Georgia, Louisiana, and other Southern states. This included secretive funding of litigation resulting in Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 (1903), which lost because of the Supreme Court’s reluctance to interfere with states’ rights.