Happy Hump Day POU! We continue looking at great stories that could make for great screenplays, although today’s entry could easily turn into one of those “white savior” stories that Hollywood loves (blech).

The remarkable Jack Macon was owned by Maury County Tennessee resident William H. Macon — the nephew of early North Carolina Sen. Nathaniel Macon, for whom all towns, cities and counties called Macon are named. When Jack showed a propensity for healing the sick and the lame, William sent him out to take on some white patients, even though it was illegal for slaves to practice medicine. Dr. Jack then amassed a loyal clientele.

Doctor Jack became known for his abilities to use roots and herbs to heal the sick. His services were available both to members of the black community and to whites. As Jack’s work as a healer became known throughout the south, some local residents began to criticize his work. In 1843, locals in Fayette County Tennessee began to protest the fact that Jack was allowed to freely roam and practice medicine wherever he wished. During this time many rootworkers in the south were forbidden to practice medicine by the institution that supported slavery. Racism and jealousy led to complaints filed with the Fayette County Circuit Court in the hopes of imposing fines on Jack’s owner.

Since Jack wasn’t legally a person, when he was busted, William got in trouble. In 1831, Dr. Jack’s patients petitioned the state government to find a way to let him practice medicine without breaking the law. The state legislature declined. William and Jack moved clear across the state to Fayette County, where Jack continued to practice medicine illegally (and financially rewarding William). In 1843, his white patients again petitioned the state legislature to give Dr. Jack an exemption to the law. This too failed.

Surprisingly it was a group of highly influential women in the white community that decided to come to Jack’s rescue. In November of 1843, a group of sixty-seven women traveled to the state capitol to petition the Tennessee legislature to modify a law that was being used to repress Doctor Jack’s ability to practice. Tennessee Act 1831 c. 103, S.3 was frequently used to prohibit slaves from practicing medicine. The women’s petition asked the state to repeal, amend or modify the act in order for Doctor Jack to be able to practice.

The petition’s abstract reads, “Sixty-seven ladies residing in Tennessee respectfully petition the Honorable Legislature of the State to repeal, amend or so modify the Act of 1831 c. 103. S.3 which prohibits slaves from practicing medicine as to exempt from its operation a slave named Jack the property of William H. Macon. They believe ‘Doctor Jack’ to be honest, honorable and skillful, especially in obstinate cases of long standing; and that the people ought not to be denied the privilege of commanding his services.”

The petition was accompanied by a number of testimonies regarding Doctor Jack and his ability as a rootworker. The testimony of a Wade Barret from Giles County, Tennessee, regarding Doctor Jack’s ability to heal his sick wife speaks of Jack’s efficiency as a healer as opposed to conventional physicians in the region:

“I do certify that my wife (Amelia) was taken unwell about the first of August 1829. She complained of great misery in the back and loins, together with a numbness in her thighs which threw her to bed the 19th of the same month. I immediately applied to a physician who formerly waited on my family from which she took medicine for about six weeks without receiving any benefits. I then applied to another, who I thought to be the best physician in the country, who attended on her about one month without the least apparent benefit, but she still grew worse and it was the opinion of the most of my neighbors that she must sink under her complaint if not speedily removed. In this case she was when about the first of December following I employed Doctor Jack (a colored man) belonging to William Macon of Maury County Tennessee, ten miles west of Columbia, who undertook her, he commenced with roots and to my great astonishment in a few days she began to amend and in a few weeks she was up and attending to her ordinary business of life and I believe she is as well at this time and enjoys as good health as she has done for several years.”

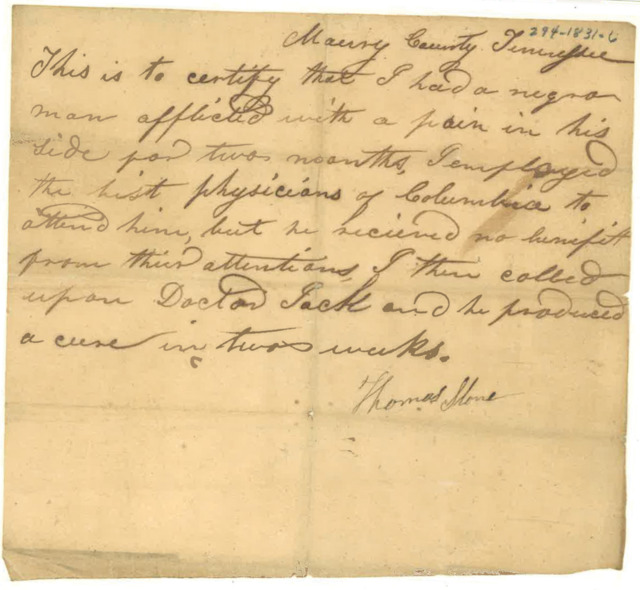

A testimony submitted by a “L. Harwell” testified that Jack provided services for a fellow slave:

“This is to certify that some time in the summer of 1829 that I had a negro man in a low lingering way and sunk under his complaint so rapidly that soon became entirely unfit for service, his disease seemed to threaten an immediate dissolution when I employed a Negro man called Doctor Jack belonging to W. Macon of Maury County Tennessee who commenced to doctor him with indigenous roots and to my surprise in a few weeks relieved him of all his complaints and in a few months I believe made a perfect cure. The negro is now well and fit for the hardest service given under my hand.”

Ten years later, Jack Macon was listed in the first Nashville city directory among the other doctors — “Jack, Root Doctor, Office — 20 N Front St.” Since he has no last name, we can surmise that he was still a slave — a slave illegally practicing medicine in the open, mere blocks from the legislature that refused to let him practice legally. For whatever reason, no one in Nashville troubled him about it. There’s no record of him being freed, but interment records at the Nashville City Cemetery state that Jack died a free man of color, “known as Dr. Jack,” on May 16, 1860, at the age of 80.