GOOD MORNING, P.O.U.!

We continue our series on the Aboriginal massacres of Australia.

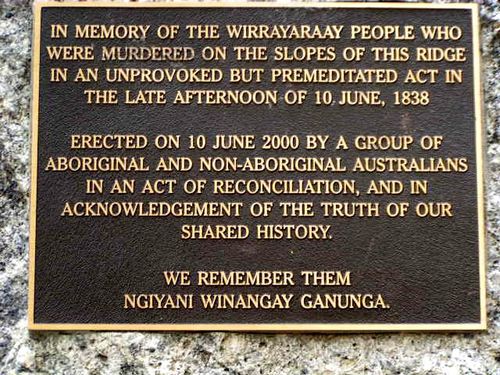

MYALL CREEK MASSACRE OF 1838

In 1838 white settlers murdered 28 Aboriginal men, women and children near Myall Creek Station. For the first time in history some killers were tried and hanged.

The massacre is a harrowing reminder of Australia’s colonial violence.

What happened at Myall Creek?

On 10 June 1838 a group of white settlers murdered 28 Aboriginal men, women and children near Myall Creek Station in northern New South Wales, near Bingara. Seven of the killers were tried and hanged.

The Myall Creek Massacre now serves as both a harrowing reminder of Australia’s colonial violence towards Aboriginal people and an example of modern-day reconciliation.

Historic background

In 1838 white people had settled Australia for just 51 years. Pastoralists were pushing into Aboriginal land, dispossessing Indigenous people from the land that nurtured them physically and spiritually.

Aboriginal people did not give up their land that they had looked after for millennia without a fight. White settlers engaged in many clashes with Aboriginal people at the frontier. Fearing to be outnumbered by Aboriginal tribes some settlers escalated low-level skirmishes to the atrocities we now know as Australia’s massacres of Aboriginal people.

With the eyes of the law often several days’ ride away the settlers had little to fear. Gangs of stockmen went on what was known as ‘the Big Bushwhack’ or simply ‘the Drive’: a hunt for Aboriginal people which lasted several months [2]. They thought there was nothing wrong with shooting Aboriginal people or raping Aboriginal women.

Among the massacres, the one at Myall Creek differs from the many other massacres of Aboriginal people in that it is a well documented and extreme example of what white people were capable of perpetrating on Aboriginal peoples.

Note, however, that the Myall Creek massacre if not famous for what happened to the Aboriginal victims, but for what happened to the white perpetrators.

The events of the Myall Creek Massacre on June 10, 1838

Many massacres, including Myall Creek, were witnessed only by the murderers. But because the Myall Creek Massacre has been extensively documented we know now what happened.

At the time about 50 Aboriginal people had moved to Myall Creek Station at the invitation of a stockman employed there.

Ten of them, all able bodied males, were working on a neighbouring station, 50kms away, when they learned that a group of armed stockmen planned to go onto Myall Creek Station. They walked back as fast as they could, but it was already too late.

The stockmen, led by John Fleming, were already galloping towards the huts of Myall Creek Station where the remaining Aboriginal people were preparing their evening meal.

The stockmen herded the defenceless Aboriginal people together and tied their hands together with a long rope. Only two young boys escaped.

The men were deaf to the cries of their victims. Within twenty minutes of their arriving they hauled their captives westwards from the huts and over the top of a rise.

About 800 metres from the huts the defenceless Aboriginal people were hacked and slashed to death. They were beheaded and their headless bodies were left where they fell. The stockmen then set up camp, drinking and bragging about their killings.

Late that night the Aboriginal men who had been working at the neighbouring station arrived at Myall Creek Station. They were urged to move on and headed off into the night.

Two days after the Myall Creek Massacre the murderers returned and burned the bodies of their victims. They then set out to find the ten Aboriginal people they had missed.

They found them the next day and murdered most of them.

It seems likely that the same stockmen perpetrated another massacre near MacIntyre’s (near Inverell) where the group of ten Aboriginal people had headed. Reportedly between 30 and 40 Aboriginal people were murdered and their bodies cast onto a large fire.

A woman was allowed to run with blood spurting out of her cut throat. She was then thrown alive onto the fire. Her infant child was thrown alive onto the fire. Two young girls were mutilated by the gang.

Eventually the party immersed into heavy drinking and dispersed five days after their first killings.

Almost three weeks later the atrocity was reported to police in Sydney in the absence of the local police magistrate. Governor George Gipps ordered an investigation which opened on July 28th, 1838. Eventually ten suspects were identified and marched 300kms to Sydney for trial. Their leader, John Fleming, escaped.

As news spread about the prisoners their capture attracted wide interest. Given the accepted opinion about Aboriginal people of those days the public were soon in favour of the accused and a prominent landholder offered to finance their defence.

The first trial in November 1838 was based on thin evidence. No-one apart from the killers had witnessed the massacre and they had removed all bodies before they could be recovered as evidence. The accused pleaded not guilty.

In the absence of any corpse the jury took only 15 minutes to pronounce the accused not guilty to the cheering of the crowd in the court. But Attorney-General James Plunkett asked for and was granted another indictment.

The second trial, ten days later, accused only seven of the original ten men and focused on the killing of just one Aboriginal child. Eventually the jury found them guilty of the murder of the child.

On 18 December 1838 the seven stockmen were hanged. For the first time in Australian history white men were punished for murder of Aboriginal people [3].

But the NSW governor’s commitment to justice for Aboriginal people waned. The involvement of the other three men in the Myall Creek Massacre was never investigated.

The verdict and sentence caused outrage among settlers [2,3]. Petitions were signed and money was raised to employ the best lawyers to defend the murderers [14]. For the murderers it was inconceivable that they had committed a crime given that there had been many such killings. Often the leader of a ‘punitive party’ and the magistrate responsible for trials were one and the same man [3,11].

After Myall Creek

After the Myall Creek Massacre murderous attacks on Aboriginal people continued for many decades well into the 20th century. White people now went ‘underground’ using poisoned flour [2] which was harder to prove in court [13]. They also took greater care to conceal or destroy the corpses [13]. Many massacres never became known outside the district where they occurred [3].

One of the last big massacres occurred in 1928 when a group of policemen chained together and shot 50 Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory. Three women were spared to be raped and later burned [10]. It became known as the Coniston Massacre.

Overall, “premeditated butchery of men, women, children and infants accounted in the aggregate for tens of thousands of black lives,” reported the Sydney Morning Herald [14], a view Colin Clague confirms. Colin was head of the Aboriginal Land Claims Unit from 1983 to 1988 and vividly remembers the struggle to acknowledge many other massacre sites. Many of them could not be claimed, and when you walk along public reserves or in national parks you might as well come across a massacre site [17].

Myall Creek is all over Australia.

READ MORE: Creative Spirits