Good Morning POU. We continue looking at the period of Reconstruction.

Many Southern planters attempted to hide the news of emancipation from enslaved people, using threats and violence to force silence and attacking those who dared attempt to flee. Where federal troops were present, however, many enslaved people courageously fled bondage and sought protection and freedom in Union camps. For the many more enslaved people living where federal forces were absent or unreachable, Lincoln’s declaration did nothing, and the hold of enslavement lasted well beyond 1863. Up until the war’s end in 1865, local newspapers in Montgomery, Alabama, continued to advertise auction sales of enslaved people and publish ads seeking the return of “runaways.”

In an August 1864 letter, a Black woman named Annie Davis living in Maryland asked Lincoln himself to clarify whether she remained in bondage. “Mr. President,” she began,

It is my Desire to be free. To go to see my people on the Eastern Shore. My mistress wont let me. You will please let me know if we are free and what I can do. I write to you for advice. Please send me word this week. or as soon as possible and oblidge [sic].

Ms. Davis’s letter survives at the National Archives among correspondence received by the Colored Troops Division. There is no evidence she ever received a reply.

Most white people refused to accept Emancipation and Black citizenship. They instead responded to Reconstruction’s progress by using force and terror to disenfranchise, marginalize, and traumatize Black communities while killing countless Black people.

As Reconstruction continued, the terror attacks that white mobs committed grew more structured and group-based. “A lawlessness which, in 1865-1868, was still spasmodic and episodic, now became organized,” W.E.B. Du Bois later observed. “Using a technique of mass and midnight murder, the South began widely organized aggression upon the Negroes.”

Shortly after passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, white mobs began to target Black people simply for claiming their freedom.

On July 30, 1866, at what is today the Roosevelt Hotel, New Orleans was hosting a convention of white men working to make sure Louisiana’s new constitution would guarantee Black voting rights. In the weeks leading up to the convention, local press denounced the attendees as traitors and invaders. “Within a short time,” warned the Louisiana Democrat, “we may expect to see the State of Louisiana a member of the Union, with nigger suffrage, nigger Senators, and nigger representatives.”

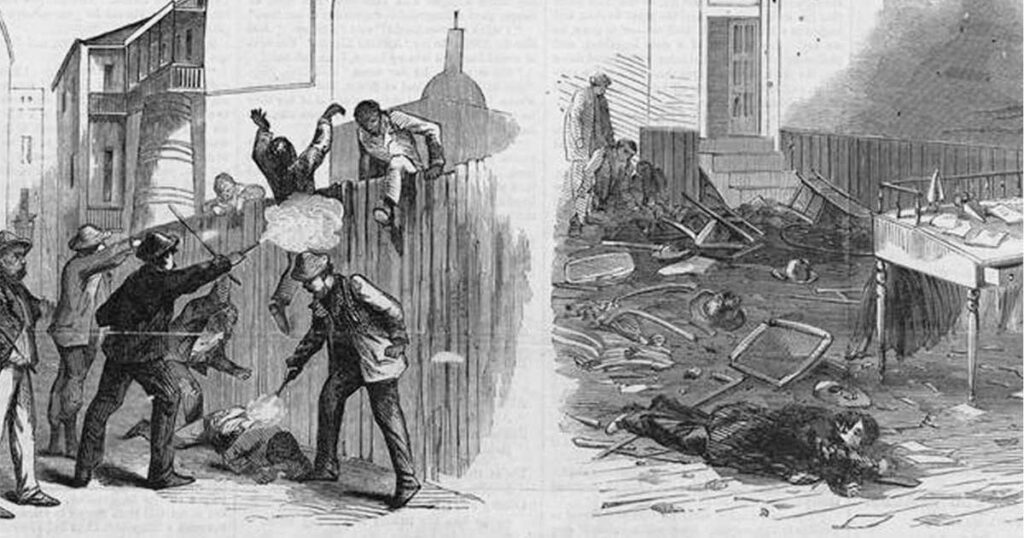

When local Black men staged a march to support the convention, the seething opposition erupted in violence as white police and mob members indiscriminately killed Black people in the area. “For several hours, the police and mob, in mutual and bloody emulation, continued the butchery in the hall and on the street, until nearly two hundred people were killed and wounded,” a Congressional committee formed to investigate the massacre concluded in 1867. “How many were killed will never be known. But we cannot doubt there were many more than set down in the official list in evidence.”

Organized and violent white resistance to Reconstruction was born in Pulaski, Tennessee, on December 24, 1865, when six Confederate veterans formed the first chapter of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Functioning from its inception as a political paramilitary arm of white supremacist interests, the Klan engaged in a campaign of terror, violence, and murder targeting African Americans and white people who supported Black civil rights. The Klan and similar organizations, including the Knights of the White Camelia and the Pale Faces, were largely independent and decentralized but shared aims and tactics to form a vast network of terrorist cells. By the 1868 presidential election, those cells were poised to act as a unified military force supporting the cause of white supremacy throughout the South.

In Georgia on October 29, 1869, Klansmen attacked and brutally whipped 52-year-old Abram Colby, a formerly enslaved Black man who had been elected to Congress by enfranchised freedmen. Shortly before the attack, a group of Klansmen comprised of white doctors and lawyers tried to bribe Mr. Colby to change parties or resign from office.64 When he refused, the men brutally attacked him. Mr. Colby later testified before a Congressional committee:

[The mob] took me to the woods and whipped me three hours or more and left me for dead.

In Chattanooga, Tennessee, when a Black man named Andrew Flowers defeated a white candidate in the 1870 race for justice of the peace, Klansmen whipped him and told him that “they did not intend any nigger to hold office in the United States.”

On the night of March 6, 1871, a mob of armed white men hanged a Black man named James Williams in York County, South Carolina, and terrorized the local African American community, assaulting residents and burning homes. Mr. Williams, enslaved before the Civil War, had recently organized a coalition to protect the freedom of Black people in York County. White residents circulated rumors claiming that he posed a threat,69and as his former enslaver later testified, his presence “caused a great deal of uneasiness.” Details of the lynching were sparsely documented but federal officials arrested and prosecuted several alleged members of the mob. One testified during trial that, after hanging Mr. Williams, the mob stopped to get “some crackers and whiskey.”

Despite the admission, all charges were later dismissed or discontinued and no one was ever held accountable for Mr. Williams’s death.