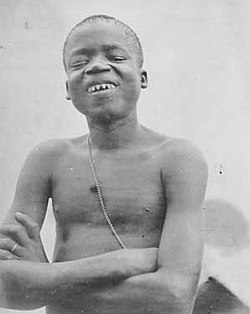

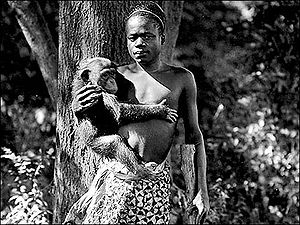

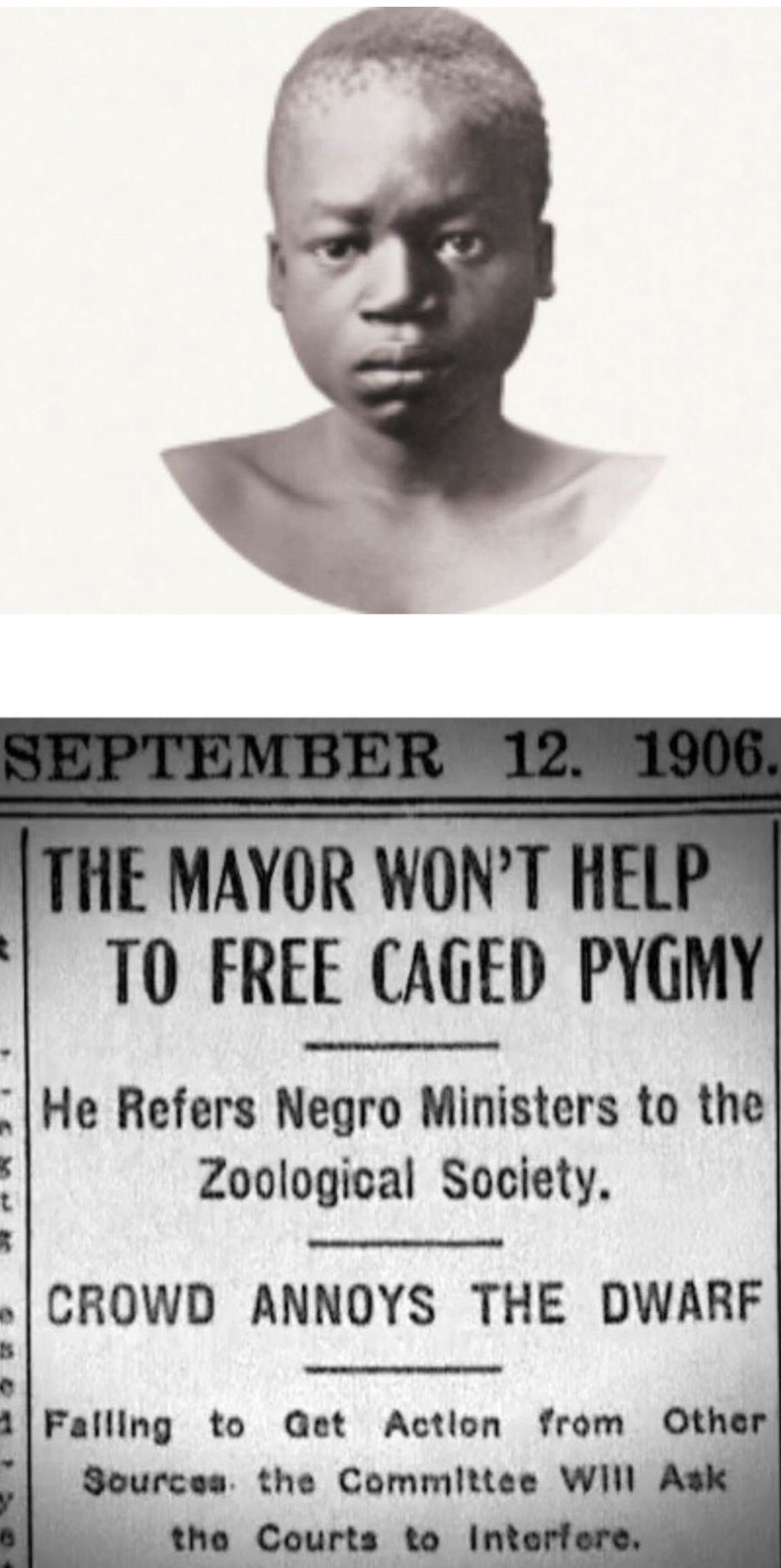

Ota Benga (c. 1883 – March 20, 1916) was a Congolese man, a Mbuti pygmy known for being featured in an anthropology exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1904, and in a human zoo exhibit in 1906 at the Bronx Zoo. Benga had been purchased from African slave traders by the missionary and anthropologist Samuel Phillips Verner, a businessman hunting African people for the Exposition.

Verner travelled to Africa in 1904 under contract from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis World Fair) to bring back an assortment of pygmies to be part of an exhibition. To demonstrate the fledgling discipline of anthropology, the noted scientist W. J. McGee intended to display “representatives of all the world’s peoples, ranging from smallest pygmies to the most gigantic peoples, from the darkest blacks to the dominant whites” to show what was commonly thought then to be a sort of cultural evolution.

Verner discovered Ota Benga while ‘en route’ to a Batwa village visited previously; he negotiated Benga’s release from the slave traders for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth. Verner later claimed Benga was rescued from the cannibals by him. The two spent several weeks together before reaching the village. There the villagers had developed distrust for the muzungu (white man) due to the abuses of King Leopold’s forces.

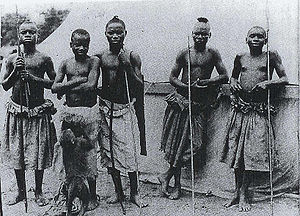

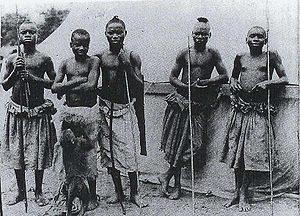

Verner was unable to recruit any villagers to join him until Benga spoke of the muzungu saving his life, the bond that had grown between them, and his own curiosity about the world Verner came from. Four Batwa, all male, ultimately accompanied them. Verner recruited other Africans who were not pygmies: five men from the Bakuba, including the son of King Ndombe, ruler of the Bakuba, and other related peoples – “Red Africans” as they were collectively labeled by contemporary anthropologists.

At the Bronx Zoo, Benga had free run of the grounds before and after he was exhibited in the zoo’s Monkey House. Except for a brief visit with Verner to Africa after the close of the St. Louis Fair, Benga lived in the United States, mostly in Virginia, for the rest of his life.

Displays of non-white humans were examples of white supremacists ideologies and world domination during the early 20th century and were justified using the thesis of evolution. These racist human exhibitions were supposed to display “earlier stages” of human evolution in the early 20th century. Racial theories were arrogantly used because of the denial of a knowledge of biology.

African-American clergymen immediately protested to zoo officials about the exhibit. Said James H. Gordon,

“Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes … We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls.” Gordon thought the exhibit was hostile to Christianity and a promotion of Darwinism: “The Darwinian theory is absolutely opposed to Christianity, and a public demonstration in its favor should not be permitted.”

In defense of the depiction of Benga as a lesser human, an editorial in The New York Times suggested:

We do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter … It is absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation Benga is suffering. The pygmies … are very low in the human scale, and the suggestion that Benga should be in a school instead of a cage ignores the high probability that school would be a place … from which he could draw no advantage whatever. The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education out of books is now far out of date.

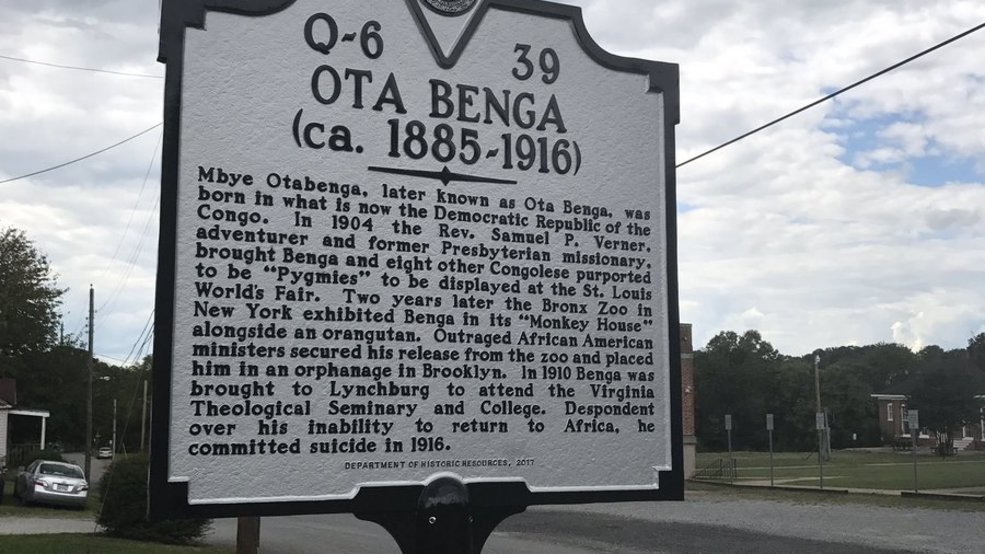

African-American newspapers around the nation published editorials strongly opposing Benga’s treatment. Dr. R. S. MacArthur, the spokesperson for a delegation of black churches, petitioned New York City Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. for his release from the Bronx Zoo.

NYC Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. refused to meet with the clergymen, drawing the praise of Hornaday, who wrote to him: “When the history of the Zoological Park is written, this incident will form its most amusing passage.”

As the controversy continued, Hornaday remained unapologetic, insisting that his only intention was to put on an ethnological exhibition. In another letter, he said that he and Grant—who ten years later would publish the racist tract The Passing of the Great Race—considered it “imperative that the society should not even seem to be dictated to” by the black clergymen.

On Monday, September 8, 1906, after just two days, Hornaday decided to close the exhibition, and Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd “howling, jeering and yelling.”

The mayor released Benga to the custody of Reverend James M. Gordon, who supervised the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn and made him a ward. That same year Gordon arranged for Benga to be cared for in Virginia, where he paid for him to acquire American clothes and to have his teeth capped, so the young man could be more readily accepted in local society. Benga was tutored in English and began to work. Soon he made plans for a return to his homeland in the Congo.

In 1914 when World War I broke out, a return to the Congo became impossible as passenger ship traffic ended. Benga became depressed as his hopes for a return to his homeland faded. On March 20, 1916, at the age of 32, he built a ceremonial fire, chipped off the caps on his teeth, and shot himself in the heart with a stolen pistol.

He was buried in an unmarked grave in the black section of the Old City Cemetery, near his benefactor, Gregory Hayes. At some point, the remains of both men went missing. Local oral history indicates that Hayes and Ota Benga were eventually moved from the Old Cemetery to White Rock Cemetery, a burial ground that later fell into disrepair.