Textile maker WestPoint Stevens can trace its roots to the pre-Civil War era through Pepperell Manufacturing, a company founded in 1851 and bought by WestPoint in 1965.

Two Pepperell histories describe the company’s ties to Southern planters, who supplied Pepperell with cotton and were among the buyers of its rough-milled fabric, called “Negro cloth.”

Pepperell’s Rock River fabric brand was “a sturdy cloth heavily bought by Southern plantation owners as clothing for their Negro slaves,” says The Men and Times of Pepperell, a book published by the company in the 1940s to celebrate its history.

In the mid-19th century, many Northern mills concentrated on making cheap fabrics, fearful they couldn’t compete with British mills making finer grades. In Rhode Island alone, 84 mills made Negro cloth or other coarse clothing for slaves, historian Myron Stachiw says.

The importance of Negro cloth went beyond its utility. It was used to remind slaves of their place in society. In 1822, the South Carolina legislature issued a decree, in response to complaints about slaves wearing ordinary clothing:

Your memorialists also recommend to the Legislature to prescribe the mode in which our persons of color shall dress. Their apparent has become so expensive as to tempt the slaves to dishonesty; to give them ideas not consistent with their conditions; to render them insolent to the whites, and so fond of parade and show as to cause it extremely difficult to keep them at home. Your memorialists therefore recommend that they be permitted to dress only in coarse stuffs, such as coarse woolen or worsted stuffs for winter –and coarse cotton stuffs for summer – felt hats, and coarse cotton handkerchiefs. Every distinction should be created between the whites and the negroes, calculated to make the latter feel the superiority of the former. It is not the intention of your memorialists to embrace in these sumptuary regulations “livery servants” as liveries however costly, are still badges of servitude. The object is to prevent the slaves from wearing silks, satins, crapes, lace, muslins, and such costly stuffs, as are looked upon and considered the luxury of dress.

Today, WestPoint Stevens is the USA’s largest producer of bed and bath textiles. It makes towels, linens and other goods for major designers and other companies. The company is now owned by Icahn Enterprises, L.P.

There were many textile mills around the South that created “the negro cloth”. This passage from The Tuscaloosa News talks about such a mill in Alabama:

Around 1830, according to historian Randall Martin Miller, a man by the name of David Scott began to see the potential for a homegrown cotton mill. Scott, originally from Massachusetts, came to the South in search of his fortune. Another Tuscaloosa newspaper, The Chronicle, had been promoting the idea, citing the success of textile mills in Georgia. The South was becoming besotted with cotton agriculture, the newspaper warned. It needed to expand its economic base to include manufacturing.

Perhaps drawing on examples in New England, Scott created “a model cotton mill complex,” complete with a company store and employee housing, on Shultz Creek, which empties into the Cahaba River in Bibb County. He bought out his partners in the late 1830s and added 300 spindles and weaving machinery.

There’s a little irony in that fact. Scott’s first product, which rolled off the mill’s looms in 1837, was slave cloth.

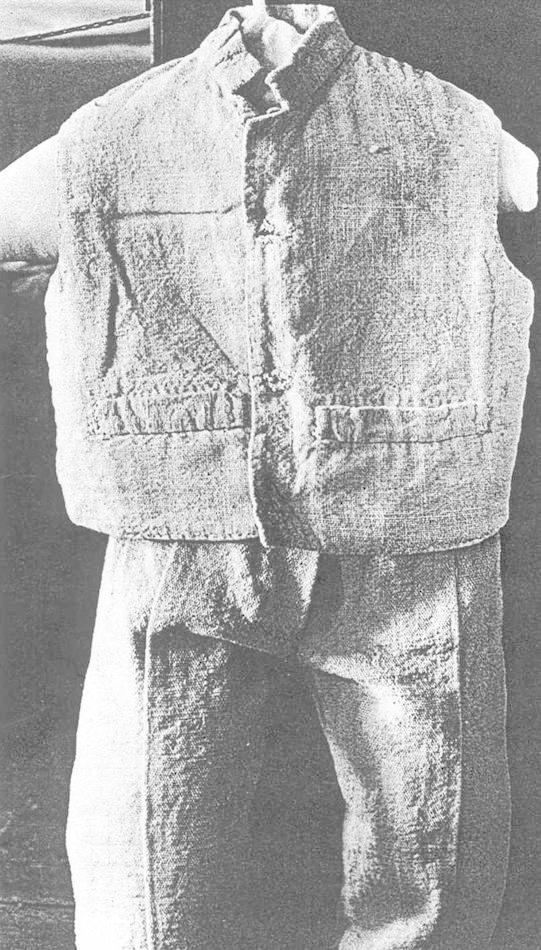

This wasn’t kente cloth, the colorful fabric made famous by the “Roots” television serial. It was a coarse material that was sold to plantation owners for slave clothing.

It was terrible stuff, similar in texture to feed bags. But it was cheap and it fit the Southern social system.

In 1822, for example, a grand jury in Charleston, S.C., issued a decree saying, “Negroes should be permitted to dress only in coarse stuffs such as coarse woolens or worsted stuffs for winter — and coarse cotton stuffs for summer … Every distinction should be created between the whites and the negroes, calculated to make the latter feel the superiority of the former.”

Any local suspicions of where Scott, the New England native, stood on the issue of slavery were erased in 1841 when he used his first $2,200 in profits to buy a family of blacks to work in the mill. They toiled alongside the poor whites that Scott hired.

Though a few other Southern mill owners had tried a mixed-race work force, it was a fairly radical move at the time. Some poor whites resented slaves taking jobs they felt were rightfully theirs. Too, some slaveowners feared that giving their bondsmen easier work than the heavy toil in the fields would empower the blacks and encourage insolence, maybe even revolt. The mill workers had Saturday afternoons and Sundays off, as well as Christmas and other holidays.

There was a deep-seated resistance to a mixed-race work force in some communities. In a Georgia mill town, whites denounced it as disgraceful and disgusting.

On the other hand, the cost of feeding and housing the slaves was cheaper even than the low salaries paid to the white mill workers. Despite the dire predictions of some critics, slaves quickly learned how to operate the mill machinery. Many mill owners actually preferred them to the sullen louts among the poor whites who turned up for textile jobs.

And as a slave owner, Scott enjoyed a step up in social status and created “Scottsville”.

As an inducement to recruit a better class of white workers, Scott built neat little houses for them near the mill. He also constructed a “tavern” as a gathering place for after-work socials, though he strictly forbade alcohol.

The introduction of slaves to the mill didn’t hurt profits in Scottsville. The operation began to return dividends as high as 33 percent. Scott, who had bought out his partners, boasted that with his slaves he could manufacture cloth at 8.5 cents a yard, compared to the lowest price of 10 cents a yard from Northern mills.

Within five years of the introduction of slave labor, he was selling shares in his company at $100 each. The factory’s capital investment had reached $70,000 — a sum equal to more than $1.5 million today.

By 1850, there were more than 200 residents at Scottsville. The mill had a work force of 77 full-time operators. Its capital investments of $117,300 made it one of the largest cotton manufacturing concerns in the state.

Scott began to broaden his line of products. The mill still produced slave cloth and heavy yarn, but it also branched into linseys, batting, fine cloth and “a superior article of cotton sewing thread,” historian Miller says.

According to Miller, Scott sold out to a J. McConnell in 1857, but the mill rolled on. By 1860, it was employing 87 whites, with wages of $8 a month for women and $12 a month for men.

The number of slaves had grown as well. A visitor at the time noted that “negro labor is much employed by them.” There were at least 30 blacks working alongside the whites.

The market value of the family that Scott bought for $2,200 in 1841 had risen to $10,000 on the eve of the Civil War. Most of the original slaves remained on their jobs at the mill, where they were described as “very useful.”

Scott wasn’t the only Northern transplant in Alabama who found himself converted by slavery’s siren call. His competitor Daniel Pratt, a New Hampshire native whose cotton works in Autauga County became famed throughout the South, wrote that “African slavery in North America has been a greater blessing to the human family than any other institution except the Christian religion.“

The Civil War would destroy those fantasies.

In 1865, Union Gen. James H. Wilson and his 13,500 cavalry troops were decimating central Alabama, purging it with fire and gunpowder. Wilson dispatched a unit under Gen. Edward McCook of Ohio to Scottsville, which was on the road between Selma and Tuscaloosa. The Union troops burned the mill complex and the town.

The mill and the community never were rebuilt.