The Rev. Otis Moss III is the senior pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago. He is the executive producer and writer of “Otis’ Dream,” a film about his grandfather’s attempt to vote in 1946.

Many Americans see this year’s election as unprecedented. For my family, it is far too familiar.

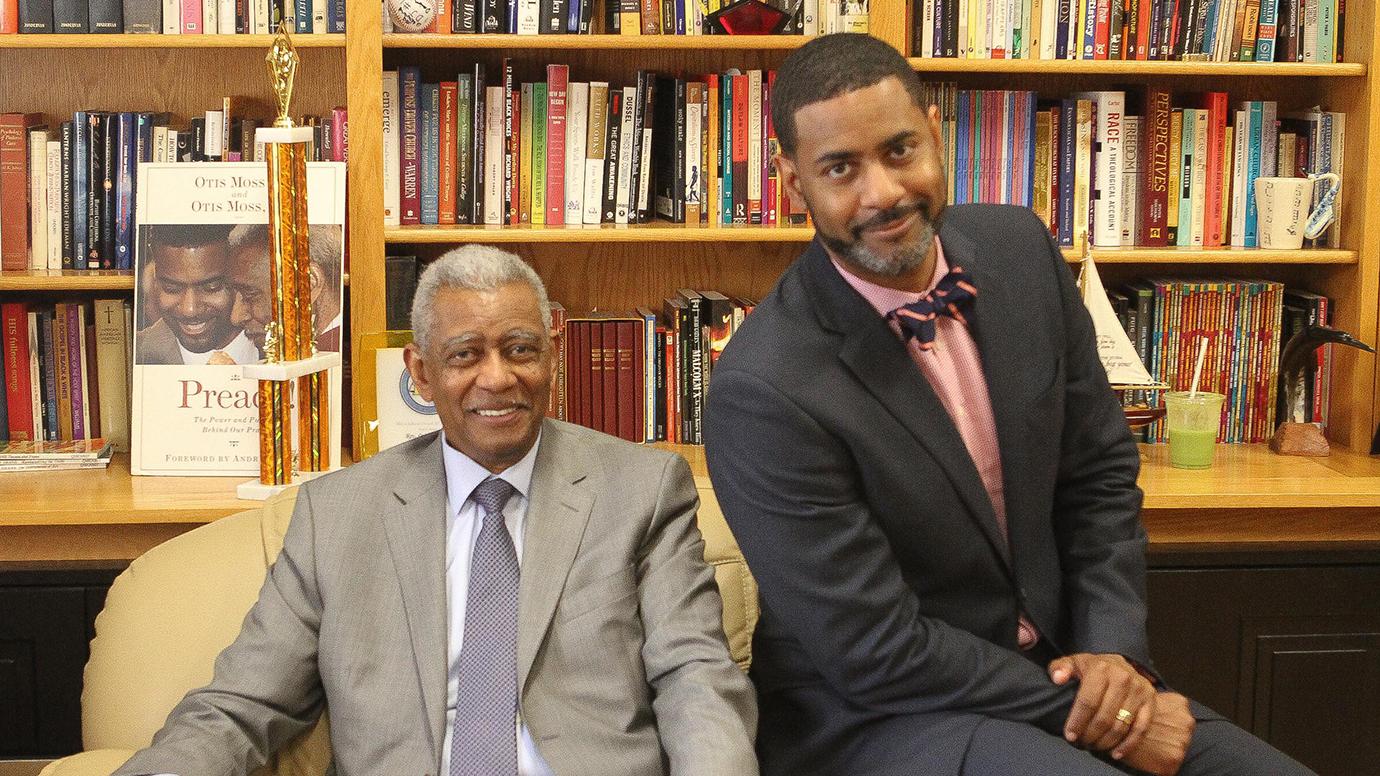

Otis Moss Jr. and Otis Moss III

On Tuesday, I will think about the grandfather I never met, Otis Moss Sr. He was a World War I veteran, sharecropper and metal smelter in rural Troup County, Ga. A widower, he kept a photo of his wife on the wall of the humble home where he raised his five children.

Those children, I have been told, could sense his pride on the morning of Nov. 5, 1946. As family history records it, Otis Sr. was excited about exercising the right that had been given — at least nominally — to Black men three-quarters of a century earlier. White supremacist and segregationist Eugene Talmadge was seeking a fourth term as Georgia’s governor. My grandfather was determined to vote him out.

I grew up hearing Otis’s children tell me how they crowded the front porch waving as their father set off on foot to the La Grange Courthouse, smartly dressed, carrying documents the county had sent identifying the courthouse as his designated polling place. When he arrived, White clerks informed him there had been a mix-up. He was supposed to have gotten a letter saying that people from his “side of town” were to vote at the Mountville School — six miles from where he stood.

Otis walked those six miles. I’m told he wiped the mud off his shoes before entering the school building, where a White clerk who wouldn’t make eye contact told him he was in the wrong place. He was supposed to vote at the Rosemont School — another six-mile journey.

By the time he arrived, it was late in the afternoon, the sun low in the sky. My grandfather’s children say that when he approached the door, he heard a lock click, and another White clerk, this one behind glass, told him that if he had arrived just five minutes earlier, he would have been allowed to vote. But polling was now closed. As a White man was allowed to enter, Otis struggled to hold on to dignity in defeat — realizing he was not fighting one person, but an entire system.

His son Otis Jr. recalls how the children ran forth to hug their father when he finally returned. “Did you vote, Papa?” they asked. His father quietly removed his hat as he walked into the house. Looking at the photo on the wall, he whispered to his dead wife: “Magnolia, not this year.”

And, for so many Black Americans, not this year, either.

Decades after my grandfather’s struggles, throughout the United States, voter suppression remains a tactic used to undermine the constitutional rights of people of African descent. President Trump has urged an “army” of his supporters to watch polling places, raising concerns of voter intimidation. He and other Republican leaders have tried to prevent ballots from being counted by moving up deadlines, restricting eligibility and limiting the number of places people can deposit ballots — such as Texas’s decision to provide one drop box for a county with nearly 5 million people.

And in Georgia, Black voters still face major hurdles to exercise their rights. Early voters this year have had to wait in line for as long as eight hours. This comes after state officials shrank the electorate in July 2017 by removing 500,000 names from the Georgia voter database — thought to be the single largest purge of registered voters in U.S. history. The majority of those eliminated were African Americans.

As Emory University’s Carol Anderson documents in her book “One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression is Destroying Our Democracy,” there is a direct linkage between today’s crackdowns and the White backlash against Black voters that affected my grandfather. Limiting polling locations, slowing down the mail, imposing arbitrary documentation requirements, intimidating voters — all the tactics now making headlines have been tools of racist voter suppression for decades. Jim Crow politicians even used the same mantra — “we are trying to stop voter fraud” — to justify their actions. In this way, Trump is the direct descendant of Talmadge.

My grandfather never got to vote in his lifetime. But his story doesn’t end there. His son, Otis Moss Jr., was forever changed by his father’s experience. He dedicated his life to advancing civil rights, working and marching alongside Martin Luther King Jr. I grew up with my father’s example and my grandfather’s story, and have committed my own ministry to fighting racial injustice. And this year I will accompany my son, Elijah Moss, to our polling location, where we will cast our votes to honor a man we never met but who lives on through us.

I would have understood if my grandfather had chosen to hide the ugliness of Nov. 5, 1946, from his children. But by telling them the truth, he unleashed generations of resistance to everything Talmadge and his enablers stood for. Whatever happens Tuesday, it may be hard for African Americans to explain the racist indignities of the Trump era, and the efforts to silence their voices in this election, to their own children. But as my family history shows, sharing these truths is the only way to make the United States a country that upholds its promises to children of all hues who are yet to be born.