Good Morning POU!

The Black Arts movement (BAM) has often been called the “Second Black Renaissance,” suggesting a comparison to the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ’30s. The two are alike in encompassing literature, music, visual arts, and theater. Both movements emphasized racial pride, an appreciation of African heritage, and a commitment to produce works that reflected the culture and experiences of black people. The BAM, however, was larger and longer lasting, and its dominant spirit was politically militant and often racially separatist.

The founding principles of this new Black America created by the Black Arts Movement focused on black power, black economics, political success, and a restructuring of the community that had been destroyed by riots and police brutality. Instituting these principles was done by using literature, art, and social institutions and black activist groups as a channel.

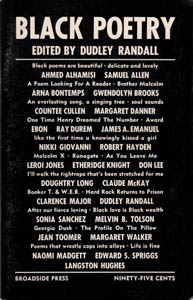

To specify the exact dates of cultural movements is difficult and, given the amorphous nature of complex cultural phenomena, may appear arbitrary. In 1965, however, several events occurred that gave direct impetus to the movement: the assassination of Malcolm X, which prompted many African Americans to take a more militantly nationalist political stance; the conversion of the literary prodigy LeRoi Jones into Imamu Amiri Baraka, the movement’s leading writer; the formation of the musically revolutionary Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) in Chicago; and the founding of Broadside Press, which became a leading publisher of BAM poets, in Detroit. Each of these events galvanized black artists.

While the movement had no specific end point, certain events and works decisively marked shifts in the cultural climate. For example, the decision in 1976 by Johnson Publishing to discontinue Black World effectively silenced the most important mass-circulation periodical voice of the movement. Furthermore, works published in 1976, such as Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls …, Ishmael Reed’s Flight to Canada, and Alice Walker’s Meridian, spoke critically and retrospectively of the movement. The major figures of the movement became less prominent in the late 1970s as new, different African-American voices began to emerge. Thus, while no one can specify when the movement ended, there was a consensus in the late 1970s that the movement was indeed over.

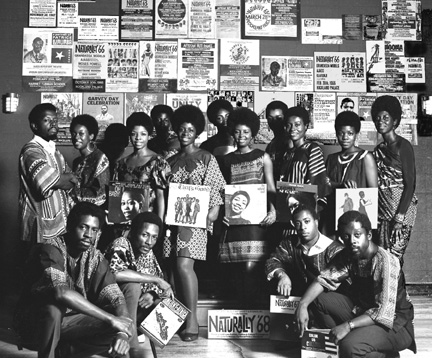

The BAM was fundamentally concerned with the construction of a “black” identity as opposed to a “Negro” identity, which the participants sought to escape. Those involved placed a great emphasis on rhetorical and stylistic gestures that in some sense announced their “blackness.” Afros, daishikis, African pendants and other jewelry, militant attitudes, and a general sternness of demeanor were among the familiar personal gestures by which this blackness was expressed.

In many cases these activists dropped their given “slave names” and adopted instead Arab, African, or African-sounding names, which were meant to represent their rejection of the white man and their embracing of an African identity. Such gestures, as they became popularized, rapidly degenerated into clichés, which have subsequently become easy targets of satire for the movement’s many detractors. Depicted in extreme forms, Afrocentric dress, soul handshakes, and other affectations of blackness appear ludicrous. Facile parodies, however, should not blind us to the serious social, cultural, and political yearnings that common gestures of personal style reflected but could not adequately express. Fads as well as profound art derived from this impulse to discover and create black modes of self-expression.

The movement is often attacked or dismissed by subsequent artists and critics as having been dogmatically hostile. Since the movement generated a great deal of polemic writing, this criticism does have a basis in fact. For example, many poems of the movement contain attacks on white people and “Uncle Tom Negroes”; many plays pontificate about the proper relationship between black men and black women (often asserting male primacy and advocating female submissiveness); musical compositions often incorporate rambling monologues of “relevant” poetry or invoke ancient African kingdoms or Malcolm X; and the images of Malcolm X and the American flag recur incessantly in the visual arts of the movement.

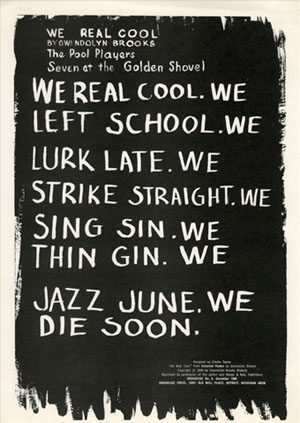

In his seminal 1965 poem “Black Art,” which quickly became the major poetic manifesto of the Black Arts literary movement, Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka by 1967) proclaimed “we want poems that kill.” He was not simply speaking metaphorically. During that period armed self-defense and slogans such as “Arm yourself or harm yourself’ established a social climate that promoted confrontation with the white power structure, especially the police (e.g., “Off the pigs”). Additionally, armed struggle was widely viewed as not only a legitimate, but often as the only effective means of liberation. Black Arts’ dynamism, impact, and effectiveness are a direct result of its partisan nature and advocacy of artistic and political freedom “by any means necessary.” America had never experienced such a militant artistic movement.

To recognize that the movement has its clichés, however, is not to suggest that cliché typifies all or even most of its works.

The two hallmarks of Black Arts activity were the development of Black theater groups and Black poetry performances and journals, and both had close ties to community organizations and issues. Black theaters served as the focus of poetry, dance, and music performances in addition to formal and ritual drama. Black theaters were also venues for community meetings, lectures, study groups, and film screenings. The summer of 1968 issue of Drama Review, a special on Black theater edited by Ed Bullins, literally became a Black Arts textbook that featured essays and plays by most of the major movers: Larry Neal, Ben Caldwell, LeRoi Jones, Jimmy Garrett, John O’Neal, Sonia Sanchez, Marvin X, Ron Milner, Woodie King, Jr., Bill Gunn, Ed Bullins, and Adam David Miller. Black Arts theater proudly emphasized its activist roots and orientations in distinct, and often antagonistic, contradiction to traditional theaters, both Black and white, which were either commercial or strictly artistic in focus.

By 1970 Black Arts theaters and cultural centers were active throughout America. The New Lafayette Theatre (Bob Macbeth, executive director, and Ed Bullins, writer in residence) and Barbara Ann Teer’s National Black Theatre led the way in New York, Baraka’s Spirit House Movers held forth in Newark and traveled up and down the East Coast. The Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) and Val Grey Ward’s Kuumba Theatre Company were leading forces in Chicago, from where emerged a host of writers, artists, and musicians including the OBAC visual artist collective whose “Wall of Respect” inspired the national community-based public murals movement and led to the formation of Afri-Cobra (the African Commune of Bad, Revolutionary Artists). There was David Rambeau’s Concept East and Ron Milner and Woodie King’s Black Arts Midwest, both based in Detroit. Ron Milner became the Black Arts movement’s most enduring playwright and Woodie King became its leading theater impresario when he moved to New York City. In Los Angeles there was the Ebony Showcase, Inner City Repertory Company, and the Performing Arts Society of Los Angeles (PALSA) led by Vantile Whitfield. In San Francisco was the aforementioned Black Arts West. BLKARTSOUTH (led by Tom Dent and Kalamu ya Salaam) was an outgrowth of the Free Southern Theatre in New Orleans and was instrumental in encouraging Black theater development across the south from the Theatre of Afro Arts in Miami, Florida, to Sudan Arts Southwest in Houston, Texas, through an organization called the Southern Black Cultural Alliance. In addition to formal Black theater repertory companies in numerous other cities, there were literally hundreds of Black Arts community and campus theater groups.