Even before controversy erupted over the novel Nigger Heaven (published in 1926), white writers such as Eugene O’Neill and Julia Peterkin were staking their fortunes on representing blacks. Peterkin, for example, whose “rich” life on a former slave plantation in South Carolina had given her “plenty of material,” spoke for numerous white writers when she declared that “Negro” culture just made for better literature than white society:

I have lived among the Negroes. I like them. They are my friends. . . . These black friends of mine live more in one Saturday night than I do in five years. I envy them, and I guess as I cannot be them, I seek satisfaction in trying to record them. . . . I shall never write of white people. Their lives are not so colorful.

Peterkin’s depictions of Gullah blacks, rather than resulting in her being banned from Harlem, actually earned her a special status in Harlem, where she was invited to review work by black writers such as Langston Hughes. Feted by NAACP officials Amy and Joel Spingarn (head Negrotarians), and praised by black critic and folklorist Sterling Brown, who applauded her “uncanny insight into the ways of our folks”, she became one of the white writers declared to be a “mentor” for black writers. When Peterkin’s Scarlet Sister Mary, a romantic post-slavery vision of black cotton pickers—“the long rows, laughing, talking . . . musical voices . . . the picking is easy. . . . Every work-day is a holiday”—won the Pulitzer Prize in 1929, many in Harlem felt compelled to read the book, and it became one of the two most popular books at Ernestine Rose’s Harlem branch library.

To many black writers, the overwhelming success of white writers felt like a return to the days of minstrelsy, when, to represent themselves, they had had to “black up” into an exaggerated, white-defined version of themselves. In a letter to Jamaican writer Claude McKay, Harold Jackman, a young black Harlemite and Countée Cullen’s intimate, wrote, “Tell me, frankly, do you think colored people feel as primitive as many writers describe them as feeling when they hear jazz? . . . There is so much hokum and myth about the Negro these days (since the Negro Renaissance, as it is called) that if a thinking person doesn’t watch himself, he is liable to believe it.” For white writers, though, it was a great opportunity. “Damn it, man,” Sherwood Anderson wrote to H. L. Mencken, “if I could really get inside the niggers and write about them with some intelligence, I’d be willing to be hanged later and perhaps would be.” White editors and publishers were offering enormous advances for “authentic” depictions of black Harlem. And they determined what qualified as black.

[whew, now take another deep breath before you read this part]

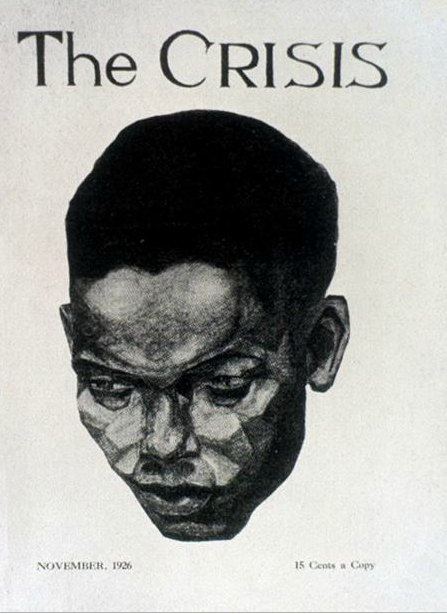

The question of black representation in the arts was the basis of a symposium entitled “The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed?” which ran monthly in The Crisis for most of 1926. It not only invited whites to weigh in on how blacks should be portrayed; it also invited Nigger Heaven author Carl Van Vechten—easily the most controversial white man in Harlem—to pen most of the questions. (For example, “Are artists or publishers under any obligations to depict people at their best?” “What is the best response to negative stereotypes?” “Is there a danger in the fascination with lower-class Negro life?”)

Dominating the symposium were whites (Negrotarians) such as H. L. Mencken, DuBose Heyward, Joel Spingarn, Mary White Ovington, publisher Alfred A. Knopf, poet Vachel Lindsay, John Farrar (founder of Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, Julia Peterkin, and others. In her response, Julia Peterkin maintained that “the crying need among Negroes is a development in them of racial pride.” “The Negro is racially different in many essential particulars from his fellow mortals of another color,” she went on, and his art needed to reflect that difference.

She then detailed the black “type” most “worthy of admiration and honor,” the type on which she felt black writers should focus. The “Mammy,” she maintained, is a “credit” to the race and “a man who is not proud that he belongs to a race that has produced the Negro Mammy of the South is not and can never be either an educated man or a gentleman.” At the end of her response, she offered to answer the question of why she wrote about black people and found them so fascinating: “I write about Negroes because they represent human nature obscured by so little veneer; human nature groping among its instinctive impulses and in an environment which is tragically primitive and often unutterably pathetic.”

Resentment over the ubiquity of such attitudes was keen. But bad feeling also had to be handled with care. Zora Neal Hurston, for example, freely told her best friend, Langston Hughes, “It makes me sick to see how these cheap white folks are grabbing our stuff and ruining it. I am almost sick—my one consolation being that they never do it right and so there is still a chance for us.” But when she repeated those sentiments to her white benefactor Charlotte Osgood Mason, writing to Mason that white people “take all the life and soul out of everything,” Mason took offense. Hurston had to backpedal or give up Mason’s help. Indeed, Hurston’s anger, though shared by almost every other black Harlemite, was usually not made public. Most black artists in Harlem were surrounded by influential or moneyed whites whose feelings needed to be taken into account.