Good morning POU! Continuing on with the week’s theme, we highlight African-American and Jewish relations regarding Entertainment and the start of the Civil Rights Movement.

Jewish producers in the United States entertainment industry produced many works on black subjects in the film industry, Broadway, and the music industry. Many portrayals of blacks were sympathetic, but historian Michael Rogin has discussed how some treatments could be considered exploitative.

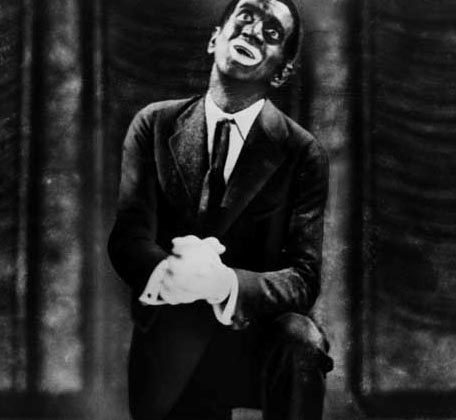

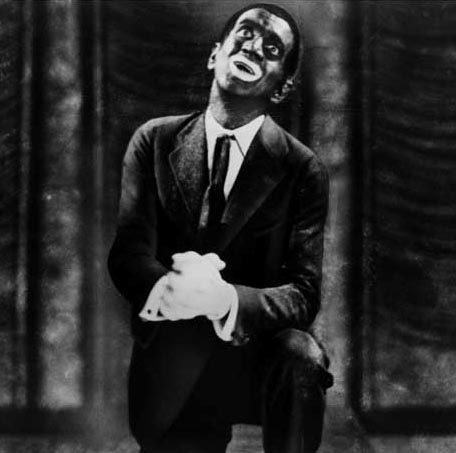

Rogin also analyzes the instances when Jewish actors, such as Al Jolson, portrayed blacks in blackface. He suggests that these were deliberately racist portrayals but adds that they were also expressions of the culture. Blacks could not appear in leading roles in either the theatre or in movies: “Jewish blackface neither signified distinctive Jewish racism nor produced a distinctive black anti-Semitism”.

Jews often interpreted black culture in film, music, and plays. Historian Jeffrey Melnick argues that Jewish artists such as Irving Berlin and George Gershwin (composer of Porgy and Bess) created the myth that they were the proper interpreters of Black culture, “elbowing out ‘real’ Black Americans.” Despite evidence from Black musicians and critics that Jews in the music business played an important role in paving the way for mainstream acceptance of Black culture, Melnick concludes that “while both Jews and African-Americans contributed to the rhetoric of musical affinity, the fruits of this labor belonged only to the former.”

Black academic Harold Cruse viewed the art scene as a white-dominated misrepresentation of black culture, epitomized by works like George Gershwin’s folk opera, Porgy, and Bess.

Some blacks have criticized Jewish movie producers for portraying blacks in a racist manner. In 1990, at an NAACP convention in Los Angeles, Legrand Clegg, founder of the Coalition Against Black Exploitation, a pressure group that lobbied against negative screen images of African Americans, alleged:

[The century-old problem of Jewish racism in Hollywood denies blacks access to positions of power in the industry and portrays blacks in a derogatory manner: “If Jewish leaders can complain of black anti-Semitism, our leaders should certainly raise the issue of the century-old problem of Jewish racism in Hollywood…. No Jewish people ever attacked or killed black people. But we’re concerned with Jewish producers who degrade the black image. It’s a genuine concern. And when we bring it up, our statements are distorted and we’re dragged through the press as anti-Semites.

Professor Leonard Jeffries echoed those comments in a 1991 speech at the Empire State Plaza Black Arts & Cultural Festival in Albany, New York. Jeffries said that Jews controlled the film industry, using it to paint a negative stereotype of blacks.

The Civil Rights Movement

Cooperation between Jewish and African-American organizations peaked after World War II—sometimes called the “golden age” of the relationship. Leaders of each group joined in an effective movement for racial equality in the United States, and Jews funded and led some national civil rights organizations. This era of cooperation culminated in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed racial or religious discrimination in schools and other public facilities, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited discriminatory voting practices and authorized the government to oversee and review state practices.

According to historian Greenberg, “It is significant that… a disproportionate number of white civil rights activists were [Jewish]. Jewish agencies engaged with their African American counterparts in a more sustained and fundamental way than did other white groups largely because their constituents and their understanding of Jewish values and Jewish self-interest pushed them in that direction.”

The extent of Jewish participation in the civil rights movement often correlated with their branch of Judaism: Reform Jews took part more frequently than did Orthodox Jews. Many Reform Jews were guided by values reflected in the Reform branch’s Pittsburgh Platform, which urged Jews to “participate in the great task of modern times, to solve, on the basis of justice and righteousness, the problems presented by the contrasts and evils of the present organization of society.”

Religious leaders such as rabbis and Baptist ministers from black churches often played key roles in the civil rights movement, including Abraham Joshua Heschel, who marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. during the Selma to Montgomery marches. Sixteen Jewish leaders were arrested while heeding a call from King to march in St. Augustine, Florida, in June 1964. It was the occasion of the largest mass arrest of rabbis in American history, which took place at the Monson Motor Lodge. Marc Schneier, President of the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding, wrote Shared Dreams: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Jewish Community (1999), recounting the historic relationship between African and Jewish Americans as a way to encourage a return to strong ties following years of animosity that reached its apex during the Crown Heights riot in Brooklyn, New York.

Northern and Western Jews often supported desegregation in their communities and schools, even at the risk of diluting their close-knit Jewish communities, which often were a critical component of Jewish life.