Good Morning POU!

“When I landed on the soil of Kansas I looked on the ground and I says this is free ground. Then I looked on the heavens and I says them is free and beautiful heavens. Then I looked within my heart and I says to myself, I wonder why I was never free before?” – former slave John Solomon Lewis

The Exodus of 1879

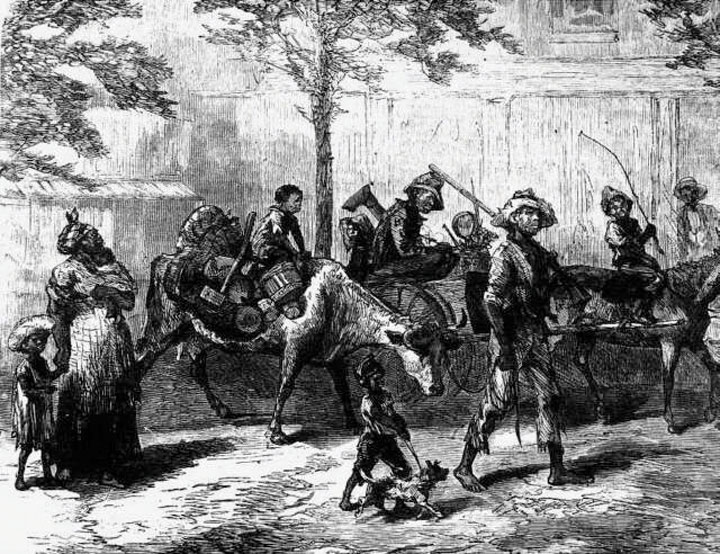

The great 1879 exodus of African-Americans was largely influenced by the outcome of 1878 elections in the state of Louisiana, in which the Democratic Party made major gains by winning several congressional seats and the governorship. Freed blacks, largely Republican supporters, were coerced, threatened, assaulted and even murdered to keep them away from the ballot box. When the final tallies were in and the Democrats claimed almost total victory, many black Louisianans knew that the time had come for them to abandon their state and join those already in Kansas. Senator William Windom, a white Republican from Minnesota, introduced a resolution on January 16, 1879, which actually encouraged black migration out of the South. The Windom Resolution, together with southern white bigotry and the letters and newspaper articles of those blacks already in Kansas, led many southern freed men and women to finally decide to make their ways to Kansas. By early 1879, the “Kansas Fever Exodus” was taking place.

John Solomon Lewis of Leavenworth, Kansas, wrote this letter on June 10, 1879. Lewis and his family were among thousands of African Americans known as “Exodusters” who escaped the harsh economic and racial realties of the Reconstruction South. The journey was difficult and many suffered hardships. Their exodus to Kansas mirrored earlier ideas about escape to Canada during slavery.

You see, I was in debt, and the man I rented land from said every year I must rent again to pay the other year, and so I rents and rents, and each year I gets deeper and deeper in debt. In a fit of madness I one day said to the man I rented from: ‘It’s no use, I works hard and raises big crops and you sells it and keeps the money, and brings me more and more in debt, so I will go somewhere else and try to make headway like white working-men.’ “He got very mad and said to me: ‘If you try that job, you will get your head shot away.’ So I told my wife, and she says: ‘Let us take to the woods in the night time.’ Well we took [to] the woods, my wife and four children, and we was three weeks living in the woods waiting for a boat. Then a great many more black people came and we was all together at the landing. Boats came along, but they would not stop, but before long the Grand Tower hove up and we got on board.

Says the captain, ‘Where’s you going?’ Says I, ‘Kansas.’ Says he, ‘You can’t go on this boat.’ Says I, ‘I do; you know who I am. I am a man who was a United States soldier and I know my rights, and if I and my family gets put off, I will go in the United States Court and sue for damages.’ Says the Captain to another boat officer, ‘Better take that nigger or he will make trouble.’

When I landed on the soil, I looked on the ground and I says this is free ground. Then I looked on the heavens, and I says them is free and beautiful heavens. Then I looked within my heart, and I says to myself I wonder why I never was free before? When I knew I had all my family in a free land, I said let us hold a little prayer meeting; so we held a little meeting on the river bank. It was raining but the drops fell from heaven on a free family, and the meeting was just as good as sunshine. We was thankful to God for ourselves and we prayed for those who could not come. I asked my wife did she know the ground she stands on. She said, ‘No!’ I said it is free ground; and she cried like a child for joy.

The 1879 exodus removed approximately 6,000 African-Americans primarily from Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas. Many had heard rumors of free transportation all the way to Kansas, but they were sorely disappointed when they discovered that such a luxury did not exist. Very few, however, were dissuaded by this inconvenience.

Many southern whites had a racist and patronizing attitude about blacks in general and the exodus in particular. As much as whites hated dealing with freed blacks, they still wanted the former slaves there as a cheap labor force. Many southern whites became so alarmed by the exodus that they began to pressure their elected officials to put a stop to it. They eventually succeeded, and a U.S. Senate committee met for three months in 1880 to investigate the cause of the exodus. The committee disintegrated into partisan bickering and accomplished little.

Despite this, blacks continued to leave for Kansas. By early March, about 1,500 had already passed through St. Louis en route to Kansas. Back in Mississippi and Louisiana, thousands more crowded onto riverbanks to wait for passing steamers to give them passage to St. Louis. One white man stated that the banks of the Mississippi River were “literally covered with colored people and their little store of worldly goods [sic] every road leading to the river is filled with wagons loaded with plunder and families who seem to think that anywhere is better than here.”

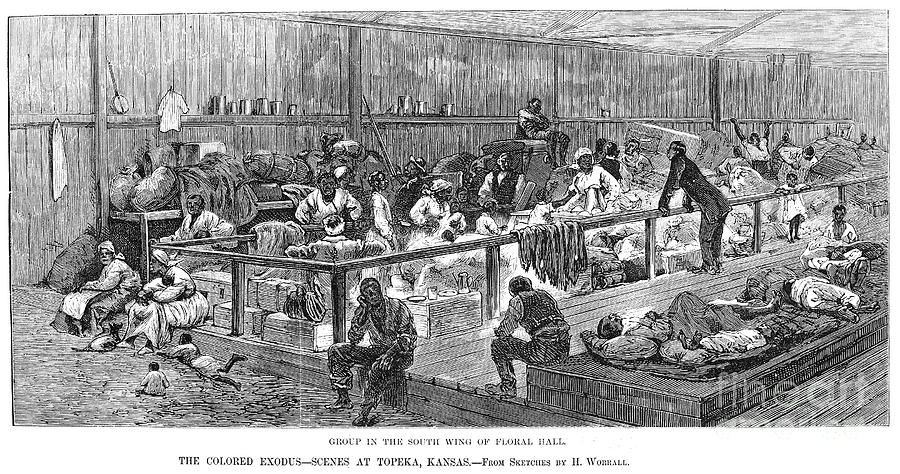

Once in St. Louis, many of the exodusters had little idea how to continue their flight with no resources. Some were so destitute that they could not feed themselves or their families. In response, St. Louis clergy and business leaders formed committees to assist the freed blacks so that they could survive and makes their ways to Kansas. Food and funds were collected from the local community as well as from sympathizers from Iowa to Ohio. Lack of shelter, however, became the most serious problem, and many blacks were forced to sleep outside near the waterfronts to which the steamships had delivered them. Care of the exodusters in St. Louis became a political issue, especially after the Democratic-leaning Missouri Republican began running anti-black stories and tales of mishandling of donated funds. By the time the last of the exodusters departed St. Louis by rail, wagon, boat or on foot, even the most sympathetic citizens were likely happy to see them go.

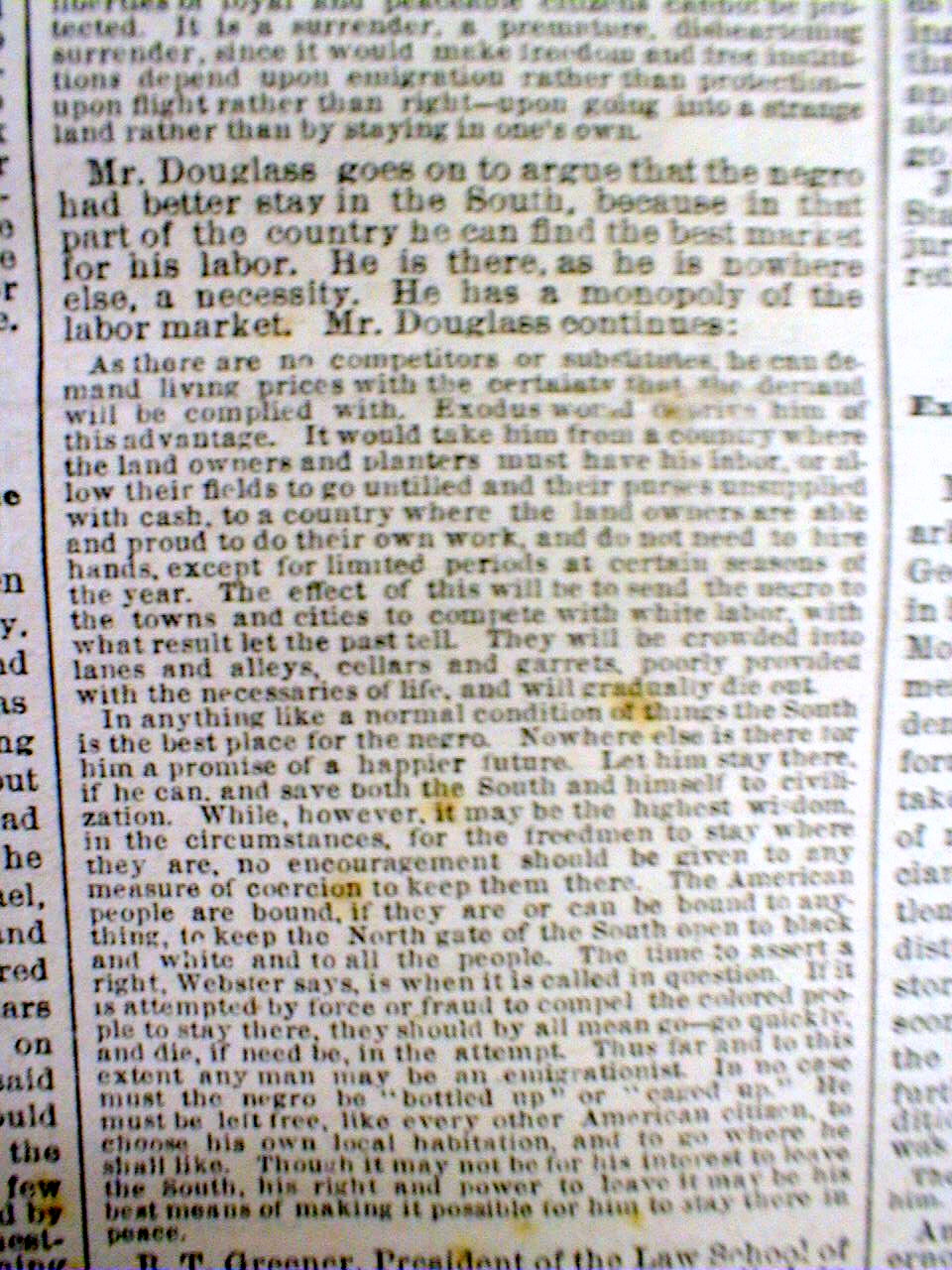

Back in the South, more African-Americans continued to plan to depart for Kansas. Black social leaders and ministers often sang the praises of the exodus, comparing it to Moses and the Israelites’ escape from Egypt. Of course, some black leaders spoke out against the exodus as well, stating that those leaving for Kansas were jeopardizing the future of those who chose to stay behind and that democracy should be given more time to work. Among the most notable of those that tried to dissuade blacks from fleeing the South was Frederick Douglass.

Southern whites continued to oppose the exodus as well. Many went to extreme measures to try to keep blacks from emigrating, including arrest and imprisonment on false charges and the old standby of raw, brute force. African-Americans suffered beatings and other forms of violence at the hands of whites desperate to keep them in the South. Though these typical forms of intimidation did not really prevent many freed blacks from leaving, the eventual refusal of steamship captains to pick them up did. One can only guess that at least some of these sailors had been threatened or paid not to offer blacks passage to St. Louis.

The 1880 Senate Investigation of the Beginnings of the African American Migration from the South

In the spring of 1879, thousands of colored people, unable longer to endure the intolerable hardships, injustice, and suffering inflicted upon them by a class of Democrats in the South, had, in utter despair, fled panic-stricken from their homes and sought protection among strangers in a strange land. Homeless, penniless, and in rags, these poor people were thronging the wharves of Saint Louis, crowding the steamers on the Mississippi River, and in pitiable destitution throwing themselves upon the charity of Kansas. Thousands more were congregating along the banks of the Mississippi River, hailing the passing steamers, and imploring them for a passage to the land of freedom, where the rights of citizens are respected and honest toil rewarded by honest compensation. The newspapers were filled with accounts of their destitution, and the very air was burdened with the cry of distress from a class of American citizens flying from persecutions which they could no longer endure.1

This quotation is from the minority report of an 1880 Senate committee appointed to investigate the causes of a mass black migration from the South during the 1870s. For African Americans, the “redemption” of the South by former Confederates after the 1876 presidential election resulted in political disfranchisement, economic repression, and relentless terror. The joyful exuberance and hope evident among the “freedmen” at the end of the Civil War—and during the heady days of Reconstruction and African American political participation—had been dashed. Many black southerners sought to escape this predicament by leaving the region and migrating to states in the North and Midwest. Chief among these destinations was Kansas.

Because of its history as the home state of abolitionist John Brown and the site of fervent “free state” sentiments during the antebellum period, black southerners viewed Kansas as a place of refuge. Many African Americans believed that Kansas was a unique state where they would be allowed to freely exercise their rights as American citizens, gain true political freedom, and have the opportunity to achieve economic self-sufficiency. These romanticized ideas of Kansas, along with the continued deterioration of their lives in the South, produced a sudden exodus. This “Kansas Exodus,” also referred to as the “Exoduster” movement, represents the first major episode in an extensive history of voluntary mass migration among African Americans.

The testimony documented in the 1880 Senate investigation has a value similar to the interviews recorded in the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) slave narratives. Whereas the slave narratives revealed the perceptions of the last generation of blacks who lived under slavery, the testimony voiced by witnesses in the Senate investigation provide first-hand accounts of the experiences and concerns of the first generation of freed blacks. Much of the testimony graphically illustrates the violence and oppression used to disfranchise and intimidate black voters during the South’s “redemption.” The testimony also reveals the beginnings of the social, political, and economic conditions that caused the Exodusters, as well as future generations of black southerners, to migrate.

This unexpected wave of migration from the South generated considerable public attention and concern throughout the nation. Many white southerners charged that northern agitators were luring away their black labor for political purposes, while northern politicians countered that the oppression of black southerners by their white neighbors was the cause. To resolve the issue, the Senate passed a resolution in December of 1879 stating:

Whereas large numbers of negroes from the Southern States are emigrating to the Northern States; and,

Whereas it is currently alleged that they are induced to do so by the unjust and cruel conduct of their white fellow-citizens towards them in the South, and by the denial or abridgment of their personal and political rights and privileges: Therefore,

Be it resolved, That a committee of five members of this body be appointed by its presiding officer, whose duty it shall be to investigate the causes which have led to the aforesaid emigration, and to report the same to the Senate; and said committee shall have power to send for persons and papers, and to sit at any time.2

The resulting committee, consisting of three Democratic senators (Chairman Daniel W. Voorhees of Indiana, Zebulon B. Vance of North Carolina, and George H. Pendleton of Ohio) and two Republican senators (William Windom of Minnesota and Henry W. Blair of New Hampshire), began to receive testimony on January 19, 1880.

The committee interviewed 153 black and white witnesses from North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Missouri, Kansas, and Indiana. Many of these witnesses augmented their personal testimony with affidavits, letters, and other forms of evidence provided by members of their local communities who were not called to testify.

The black witnesses came from a variety of social and economic backgrounds, revealing a level of class stratification that had developed in the black community soon after slavery. Several of these witnesses were members of the early educated professional class of African Americans—such as John Wesley Cromwell, a lawyer, teacher, journalist, and publisher in Washington, D.C.; O.S.B. Wall, a lawyer, former Freedmen’s Bureau agent, and colonel in the U.S. Army during the Civil War; Charles N. Otey, an editor, publisher, and teacher at Howard University; and Phillip Joseph, a journalist from Alabama. Other witnesses had served as some of the first black elected officials during Reconstruction, such as James O’Hara of North Carolina and James T. Rapier of Alabama, who had served as congressmen in the House of Representatives. George T. Ruby, a former teacher and Freedmen’s Bureau agent served as a state senator in Texas before that state’s “redemption.” Similarly, William Murrell and John Henri Burch both served as elected officials in Louisiana until that state was also “redeemed” by former Confederates. Information on some of the other black witnesses indicates that they had become successful land owners, entrepreneurs, and clergymen in North Carolina, Louisiana, and other states.

Men such as these, who had successfully attained education, property, or professional status—many of them either born or educated in the North—were viewed as the natural and expected leaders of the uneducated masses. Most of the general American public, and many in the African American community, assumed that the masses of freed blacks in the South were childlike, did not know what was best for them, and required supervision and guidance from their white superiors, or at least the from the educated class of officially recognized black leaders. Though not always based on any malicious sense of inherent superiority, many African American elites generally accepted that blacks of the uneducated class were susceptible to deception and exploitation due to their ignorance or pitiable lack of knowledge.

This perception led many among the educated black elite in the South, and national leaders such as Frederick Douglass, to vehemently oppose the exodus movement and argue that it was best for the black laborers to remain in the South. Still hoping that the federal government would provide some type of protection, these spokespersons believed that blacks stood a greater chance of regaining political power and achieving economic prosperity in the South because the majority of the nation’s African American population was already concentrated in that region. Many of the black laborers and plantation workers, however, concluded that the quality of their lives had become so bleak that fleeing the South to a new land was their only hope.

Thus the Kansas Exodus was an inconvenient blow to both whites, who expected the masses of black workers in the South to quietly conform to their new role as a cheap, compliant labor force, and to African American elites, who expected them to blindly follow the dictates of the official “black leadership” and the Republican Party. It also challenged the idea that freed blacks were incapable of intelligently assessing their own predicament, drawing their own conclusions, and taking action to improve their situation. No member of the educated elite segment of the black community directly organized or led the Exoduster movement. This grassroots movement, generated by indigenous leaders among the masses of black sharecroppers and tenant farmers, sought the full benefits of freedom.