When the U.S. Civil War began, the Union rushed to blockade Confederate shipping. White planters on the Sea Islands, fearing an invasion by the US naval forces, abandoned their plantations and fled to the mainland. When Union forces arrived on the Sea Islands in 1861, they found the Gullah people eager for their freedom, and eager as well to defend it. Many Gullahs served with distinction in the Union Army’s First South Carolina Volunteers. The Sea Islands were the first place in the South where slaves were freed. Long before the War ended, Unitarian missionaries from Pennsylvania came down to start schools for the newly freed slaves. Penn Center, now a Gullah community organization on Saint Helena Island, South Carolina, began as the very first school for freed slaves.

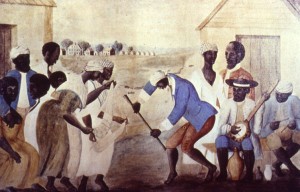

Gullah of Hilton Head, South Carolina

After the Civil War ended, the Gullahs’ isolation from the outside world actually increased in some respects. The rice planters on the mainland gradually abandoned their farms and moved away from the area because of labor issues and hurricane damage to crops. Free blacks were unwilling to work in the dangerous and disease-ridden rice fields. A series of hurricanes devastated the crops in the 1890’s. Left alone in remote rural areas in the Lowcountry, the Gullahs continued to practice their traditional culture with little influence from the outside world well into the 20th Century.

In recent years the Gullah people—led by Penn Center and other determined community groups—have been fighting to keep control of their traditional lands. Since the 1960’s, resort development on the Sea Islands has greatly increased property values threatening to push Gullahs off family lands they have owned since emancipation. They have fought back against uncontrolled development on the islands through community action, the courts and the political process.

The Gullahs have struggled to preserve their traditional culture. In 1979, a translation of the New Testament in the Gullah language began. The American Bible Society published De Nyew Testament in 2005. In November 2011, Healin fa de Soul, a five-CD collection of readings from the Gullah Bible was released. This collection includes Scipcha Wa De Bring Healing (“Scripture That Heals”) and the Gospel of John (De Good Nyews Bout Jedus Christ Wa John Write). This was also the most extensive collection of Gullah recordings, surpassing those of Lorenzo Dow Turner. The recordings help people develop an interest in the culture because people might not have known how to pronounce some words.

The Gullahs achieved another victory in 2006 when the U.S. Congress passed the “Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Act” that provides $10 million over 10 years for the preservation and interpretation of historic sites relating to Gullah culture. The Heritage Corridor will extend from southern North Carolina to northern Florida. The project will be administered by the US National Park Service with extensive consultation with the Gullah community.

Gullahs have also reached out to West Africa. Gullah groups made three celebrated “homecomings” to Sierra Leone in 1989, 1997, and 2005. Sierra Leone is at the heart of the traditional rice-growing region of West Africa where many of the Gullahs’ ancestors originated. Bunce Island, the British slave castle in Sierra Leone, sent many African captives to Charleston and Savannah during the mid- and late 18th century. These dramatic homecomings were the subject of three documentary films—Family Across the Sea (1990), The Language You Cry In (1998), and Priscilla’s Homecoming (in production).