Good Morning POU!

(if you haven’t read the novel Native Son, be forewarned that today’s post is a summary of the book)

“I had written a book of short stories which was published under the title of “Uncle Tom’s Children”. When the review of that book began to appear, I realized that I had made an awful naive mistake. I found that I had written a book which even bankers’ daughters could read and weep over and feel good about. I swore to myself that if I ever wrote another book, no one would weep over it; that it would be so hard and deep that they would have to face it without the consolation of tears.”

? Richard Wright

Perhaps no other work of literature is more important to the Chicago Black Renaissance than Richard Wright’s Native Son.

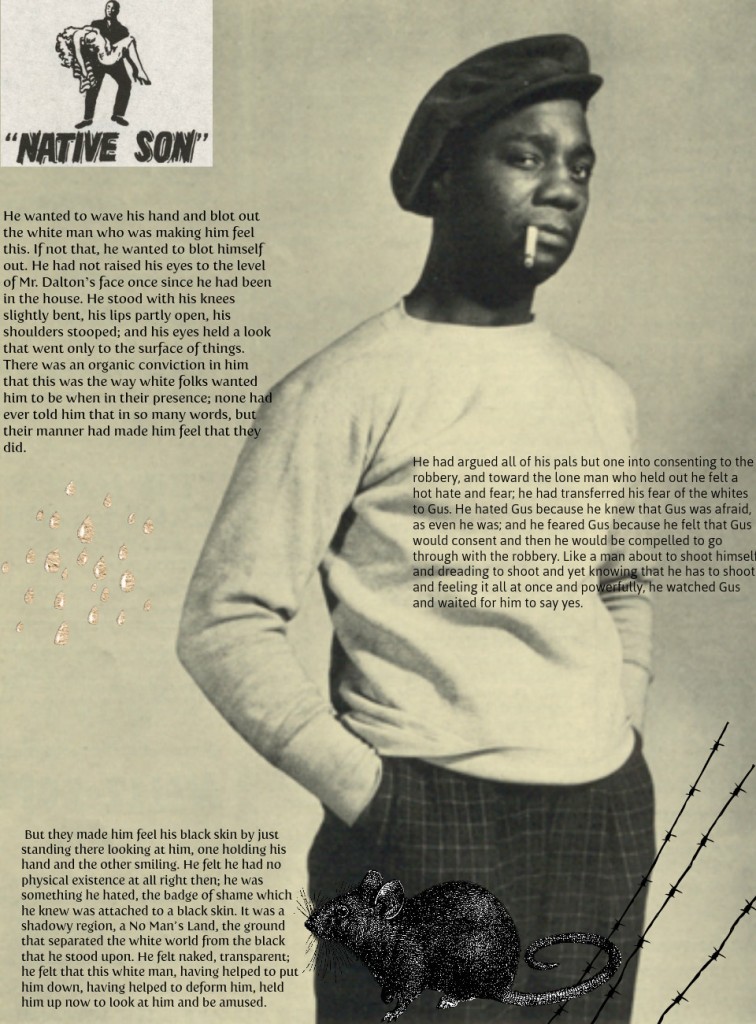

Bigger Thomas, a poor, uneducated, twenty-year-old black man in 1930s Chicago, wakes up one morning in his family’s cramped apartment on the South Side of the city. He sees a huge rat scamper across the room, which he corners and kills with a skillet. Having grown up under the climate of harsh racial prejudice in 1930s America, Bigger is burdened with a powerful conviction that he has no control over his life and that he cannot aspire to anything other than menial, low-wage labor. His mother pesters him to take a job with a rich white man named Mr. Dalton, but Bigger instead chooses to meet up with his friends to plan the robbery of a white man’s store.

Anger, fear, and frustration define Bigger’s daily existence, as he is forced to hide behind a façade of toughness or risk succumbing to despair. While Bigger and his gang have robbed many black-owned businesses, they have never attempted to rob a white man. Bigger sees whites not as individuals, but as a natural, oppressive force—a great looming “whiteness” pressing down upon him. Bigger’s fear of confronting this force overwhelms him, but rather than admit his fear, he violently attacks a member of his gang to sabotage the robbery. Left with no other options, Bigger takes a job as a chauffeur for the Daltons.

Coincidentally, Mr. Dalton is also Bigger’s landlord, as he owns a controlling share of the company that manages the apartment building where Bigger’s family lives. Mr. Dalton and other wealthy real estate barons are effectively robbing the poor, black tenants on Chicago’s South Side—they refuse to allow blacks to rent apartments in predominantly white neighborhoods, thus leading to overpopulation and artificially high rents in the predominantly black South Side. Mr. Dalton sees himself as a benevolent philanthropist, however, as he donates money to black schools and offers jobs to “poor, timid black boys” like Bigger. However, Mr. Dalton practices this token philanthropy mainly to alleviate his guilty conscience for exploiting poor blacks.

Mary, Mr. Dalton’s daughter, frightens and angers Bigger by ignoring the social taboos that govern the relations between white women and black men. On his first day of work, Bigger drives Mary to meet her communist boyfriend, Jan. Eager to prove their progressive ideals and racial tolerance, Mary and Jan force Bigger to take them to a restaurant in the South Side. Despite Bigger’s embarrassment, they order drinks, and as the evening passes, all three of them get drunk. Bigger then drives around the city while Mary and Jan make out in the back seat. Afterward, Mary is too drunk to make it to her bedroom on her own, so Bigger helps her up the stairs. Drunk and aroused by his unprecedented proximity to a young white woman, Bigger begins to kiss Mary.

Just as Bigger places Mary on her bed, Mary’s blind mother, Mrs. Dalton, enters the bedroom. Though Mrs. Dalton cannot see him, her ghostlike presence terrifies him. Bigger worries that Mary, in her drunken condition, will reveal his presence. He covers her face with a pillow and accidentally smothers her to death. Unaware that Mary has been killed, Mrs. Dalton prays over her daughter and returns to bed. Bigger tries to conceal his crime by burning Mary’s body in the Daltons’ furnace. He decides to try to use the Daltons’ prejudice against communists to frame Jan for Mary’s disappearance. Bigger believes that the Daltons will assume Jan is dangerous and that he may have kidnapped their daughter for political purposes. Additionally, Bigger takes advantage of the Daltons’ racial prejudices to avoid suspicion, continuing to play the role of a timid, ignorant black servant who would be unable to commit such an act.

Mary’s murder gives Bigger a sense of power and identity he has never known. Bigger’s girlfriend, Bessie, makes an offhand comment that inspires him to try to collect ransom money from the Daltons. They know only that Mary has vanished, not that she is dead. Bigger writes a ransom letter, playing upon the Daltons’ hatred of communists by signing his name “Red.” He then bullies Bessie to take part in the ransom scheme. However, Mary’s bones are found in the furnace, and Bigger flees with Bessie to an empty building. Bigger rapes Bessie and, frightened that she will give him away, bludgeons her to death with a brick after she falls asleep.

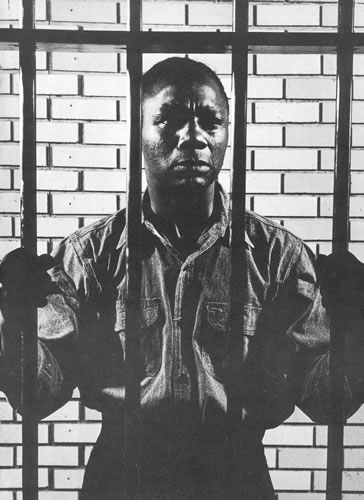

Bigger eludes the massive manhunt for as long as he can, but he is eventually captured after a dramatic shoot-out. The press and the public determine his guilt and his punishment before his trial even begins. The furious populace assumes that he raped Mary before killing her and burned her body to hide the evidence of the rape. Moreover, the white authorities and the white mob use Bigger’s crime as an excuse to terrorize the entire South Side .

Jan visits Bigger in jail. He says that he understands how he terrified, angered, and shamed Bigger through his violation of the social taboos that govern tense race relations. Jan enlists his friend, Boris A. Max, to defend Bigger free of charge. Jan and Max speak with Bigger as a human being, and Bigger begins to see whites as individuals and himself as their equal.

Max tries to save Bigger from the death penalty, arguing that while his client is responsible for his crime, it is vital to recognize that he is a product of his environment. Part of the blame for Bigger’s crimes belongs to the fearful, hopeless existence that he has experienced in a racist society since birth. Max warns that there will be more men like Bigger if America does not put an end to the vicious cycle of hatred and vengeance. Despite Max’s arguments, Bigger is sentenced to death.

Bigger is not a traditional hero by any means. However, Wright forces us to enter into Bigger’s mind and to understand the devastating effects of the social conditions in which he was raised. Bigger was not born a violent criminal. He is a “native son”: a product of American culture and the violence and racism that suffuse it.