In Charlotte’s recent history, numerous black neighborhoods have been torn down or sliced in half by highways in the name of progress. Much of this occurred in the 1960s and ’70s, as Charlotte embarked on an “urban renewal” plan that destroyed its largest black neighborhood – a community known as Brooklyn.

The original aim of the federal policy known as urban renewal was to give slum dwellers better housing. With the government’s help, cities would buy neighborhoods of dank tenements and drafty shacks, then sell at reduced prices to private developers, who would replace the slums with sound, affordable homes.

But slums usually occupied prime property in or near downtown. When cities balked at using such valuable land to house the poor, Congress allowed them to sell urban renewal property to commercial interests, as long as they found housing for displaced residents. “So in almost every American city,” says Charlotte urban historian Tom Hanchett, “the black neighborhood closest to downtown gets demolished.”

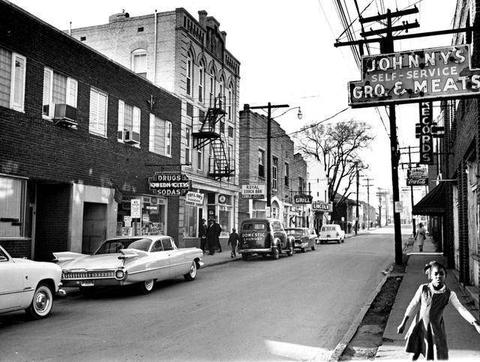

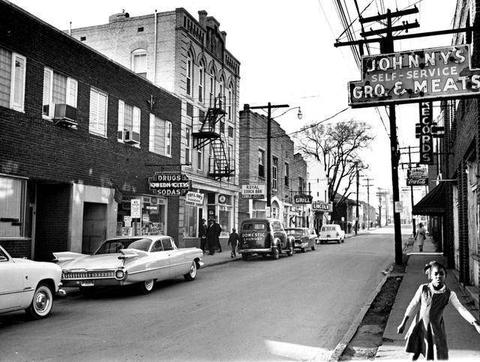

In Charlotte, that was Second Ward, the largest African-American neighborhood, also known as Brooklyn. It occupied the southern part of downtown, in the area that now includes the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Government Center and Marshall Park. Newspaper stories in the late ’50s about plans to bulldoze Brooklyn described the area as blighted and violent, a place of “narrow streets and darkened alleyways, open ditches and polluted streams,” according to a 1958 Observer editorial.

That wasn’t an accurate picture. Yes, there were slums, Hanchett says, but there were also fine houses, businesses and restaurants, a library, hotel and theater.

The history of Second Ward reaches back to the beginning of the 19 th century where the very diversified community of Second Ward thrived for several decades. The neighborhood of “Brooklyn,” taken from Brooklyn, New York in the early 1900’s, represented a self-sustainable town within a town.

The thriving mixed use neighborhood featured business ranging from J.R. Hemphill, Real Estate Man and Tailor; N.H. Tomas, Shoemaker; ACME Pressing Club; Eagles Drub Store; several barber shops and other neighborhood businesses all within the economically diverse neighborhood of Brooklyn.

It was the home to some of the most wealthy and educated, as well as poor and uneducated portions of the black community.

In 1904, it provided Charlotte with Brevard Street Library, the first free black library in the South, in 1923 it established Second Ward High School, the first urban black high school in Charlotte, as well as establishing Clinton Chapel AME Zion Church which remains a part of the current Second Ward.

Over 11 years, Charlotte tore down 1,480 structures in Brooklyn, including numerous black churches. It then sold acreage to a historically white church – First Baptist – so its congregation could expand.

The city never built new housing for Brooklyn residents. And that’s why the Beatties Ford Road corridor, which included black neighborhoods, such as Biddleville and McCrorey Heights, and white neighborhoods – Smallwood, Seversville, Wesley Heights – saw an influx of black residents in the 1960s and ’70s. When blacks moved in, whites fled, and neighborhoods that had been white became predominantly black.